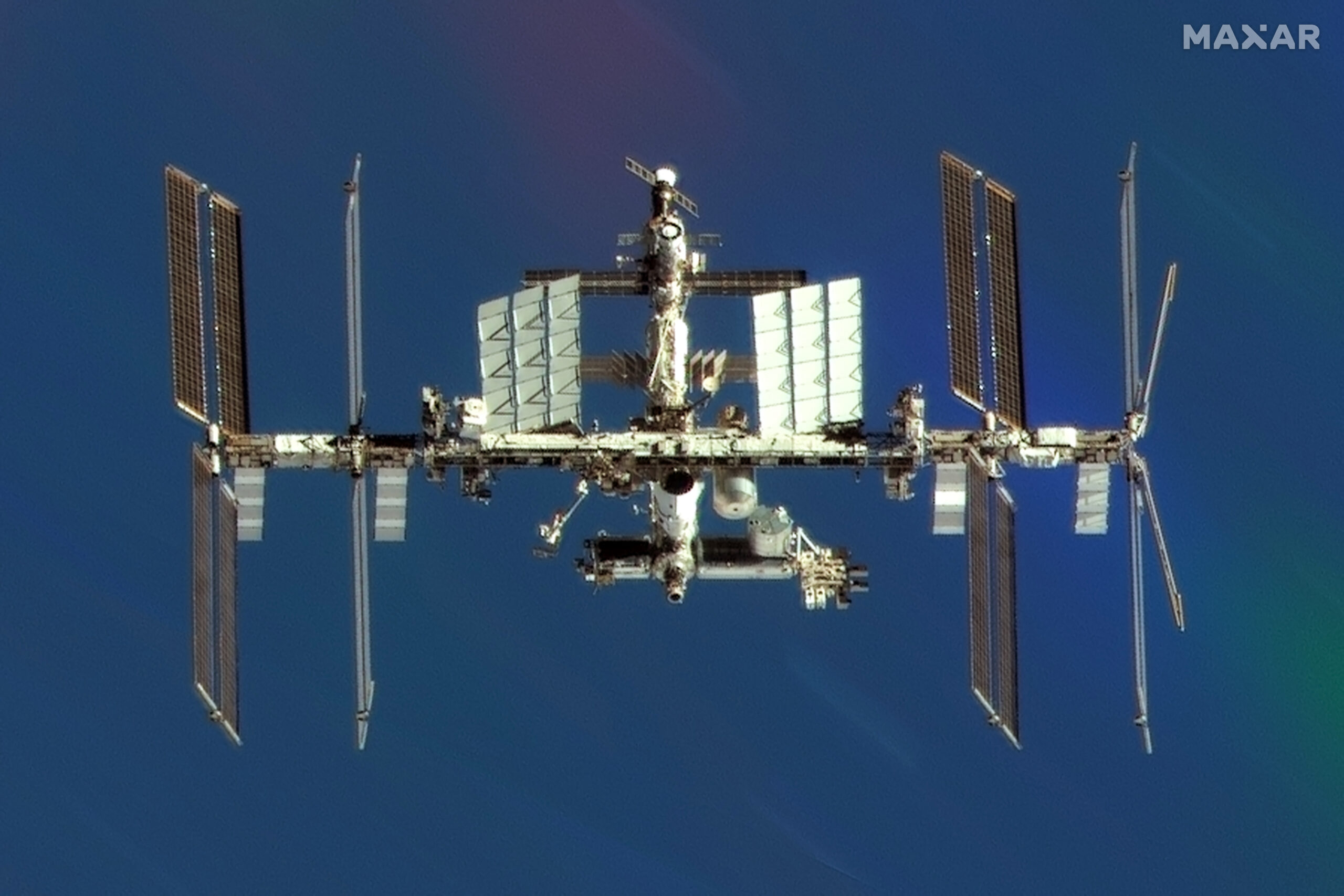

The International Space Station is the largest, most complex and most important element of space infrastructure ever deployed, and one of the most incredible engineering feats in human history. It is the result of an international, diplomatic initiative that reconciles the Western and Eastern worlds in space by combining the two space stations that had previously been planned separately by both parties – Space Station Freedom and Mir 2 – and involving five key partners, the United States, Europe, Japan, Canada and Russia.

The result is a 450-metric-ton structure that took tens of thousands of people from three continents to build for decades. It took two decades to develop and assemble in orbit, and has been permanently occupied for 20 years, at a total cost of about $100 billion to date.

The main objectives of the ISS have been achieved:

- International cooperation has been put into practice on a daily basis for decades, solving problems in space and on the ground.

- Scientific and technical experiments are constantly being conducted both inside and outside the station.

- People have lived and worked continuously and safely aboard the space station. They have maintained and repaired the space station, conducted experiments and recycled as many resources as possible.

Given the age of the ISS, the heavy budgets required to continue its operation, and the prospect of cheaper private alternatives, the partners plan to cease operations of the ISS by the end of the decade. The question then is what to do with it after 2030. Clearly, the answer to that question must be determined now in order to prepare, finance, and implement the solution that must be chosen by the partners. Doing nothing is impossible, since the ISS cannot be left unattended in its current orbit, which would decay into an uncontrolled and potentially very dangerous re-entry within a few years at most. Based on the previous experience with the re-entry of Skylab, Salyut, and Mir, the current plan is to deorbit the ISS in a controlled manner. To this end, a request for proposals for a “deorbit stage” was issued by NASA and SpaceX was selected as the supplier.

As lifelong space professionals who have worked on the redesign, assembly and operations of the ISS from various positions at ESA and NASA, we fully share the goal of ending ISS operations by the end of the decade, but we believe that destroying it would be a pointless loss for the future. We propose instead to preserve the value of the ISS by placing it in a higher orbit, so that future generations can decide how best to use the 450 tonnes of hardware already in space. We believe that the ISS will provide the cheapest half kiloton of in-space resources that humanity will ever have access to.

This is not an expensive gift for us to give to our heirs. For example, to move the ISS from its current altitude of 400 kilometers to a circular orbit of 800 kilometers would require a boost of about 220 meters per second, about the same as required for precise deorbit control. At the higher altitudes, the orbital life would be many decades, giving future generations ample time to make their own decisions and actions. To do this, the ISS would have to be left in a state where no part of it could explode and pose a long-term debris hazard.

Of course, more studies need to be done before the current people in charge can make a well-considered decision. We are no longer in charge, but our question to the current generation is: since the boost stage has to be built anyway, wouldn’t it be better to use that stage to bring the ISS into a higher orbit for possible use by a future generation, rather than destroy it upon reentry?

Jean-Jacques Dordain was Director General of the European Space Agency (ESA) from July 2003 to June 2015. During his tenure, he oversaw a number of major space missions and expanded ESA’s collaboration with international partners.

Michael D. Griffin served as NASA Director from April 2005 to January 2009, a period marked by initiatives to return humans to the Moon and develop commercial space exploration opportunities.

This article first appeared in the July 2024 issue of SpaceNews Magazine.