Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor-in-chief of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Investors are warning that political unrest in Paris is leading to a reappraisal of the financial vulnerability of the eurozone’s second-largest economy.

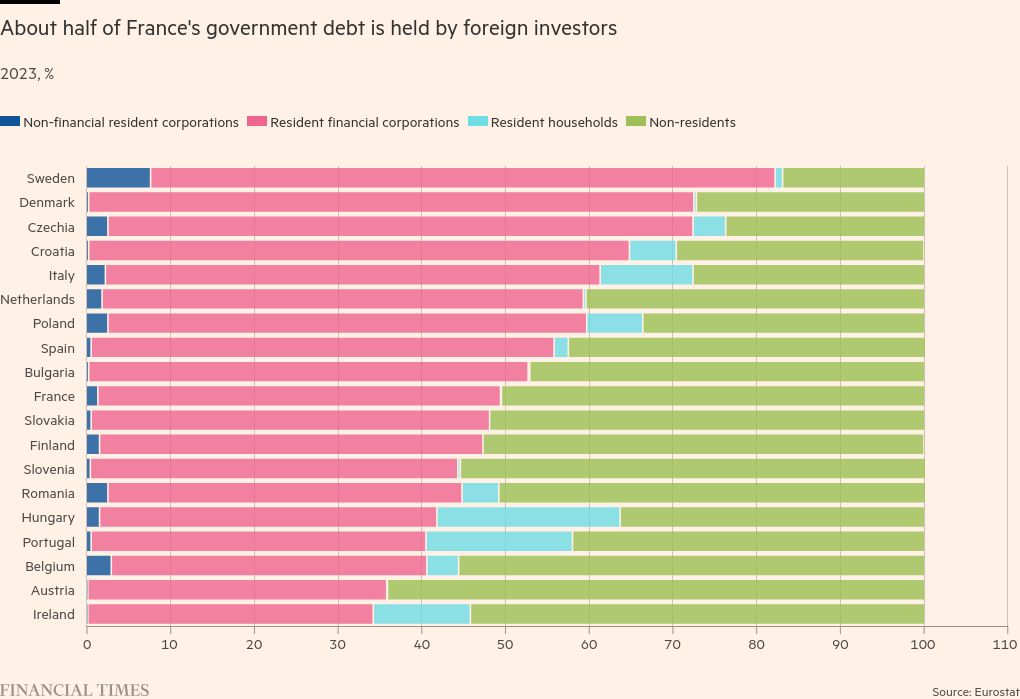

Many fear that the prospect of dysfunctional politics, slowing growth and a steadily rising debt burden will undermine France’s long-term appeal to foreign investors, who account for about half of the country’s public debt.

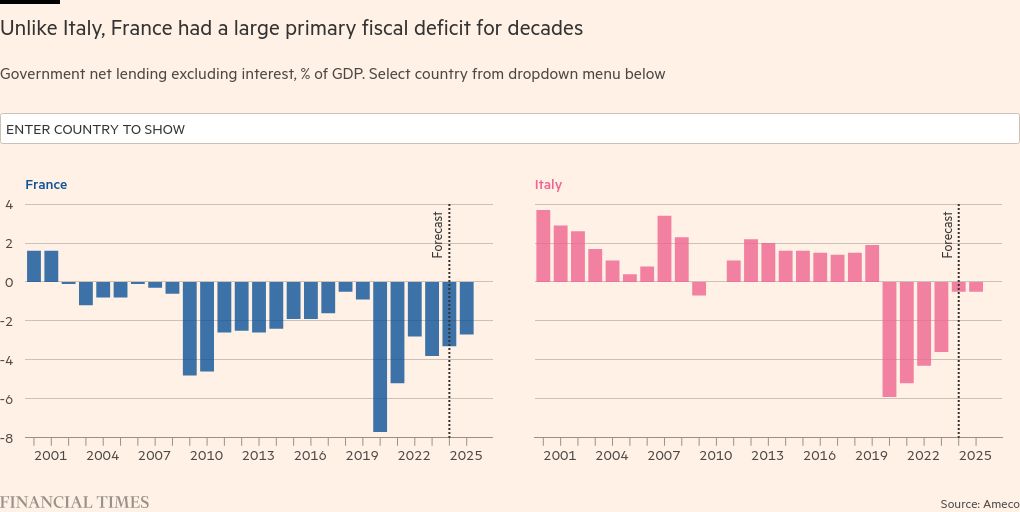

Traders doubt this will lead to turmoil similar to the 2022 crisis in the British government bond market triggered by former British Prime Minister Liz Truss, as the country’s finance minister has warned. But they fear that France’s bond market could increasingly resemble Italy’s over time, with permanently higher borrowing costs and a potential flashpoint when crises hit across the bloc.

“This is causing some consternation among investors who may have been too complacent about the political and fiscal sustainability risks in France,” said Mark Dowding of RBC BlueBay Asset Management.

If France pursues the wrong policies over time, “there is no reason why it cannot end up in a situation similar to the one Italy is in now,” he added.

Borrowing costs have already risen in response to the prospect of the far-right Rassemblement National forming the next government, or the increasingly likely prospect of an unstable and participatory parliament.

Since President Emmanuel Macron announced snap elections early last month, the spread between the yields on 10-year French and German government bonds – a measure of risk – has jumped from 0.48 percentage points to 0.85 percentage points last week, although it has since fallen to 0.71 percentage points.

According to Barclays’ Rohan Khanna, yields on French bonds are at their highest level since the early 2000s, compared with a combination of yields on ultra-safe German Bunds and traditionally riskier Spanish debt.

The first-round victory of Marine Le Pen’s RN and its allies on Sunday and the second place of the NFP have fueled fears of further political unrest before the second round on July 7. It has also heightened fears of political deadlock or a potential shift away from market-friendly policies, which could damage post-election confidence.

Pollsters believe a hung parliament or an absolute majority for the RN are the most likely outcomes after the second round. In the event of a strong finish for the RN, President Emmanuel Macron could face an uneasy power-sharing arrangement with the far-right, known as “cohabitation”.

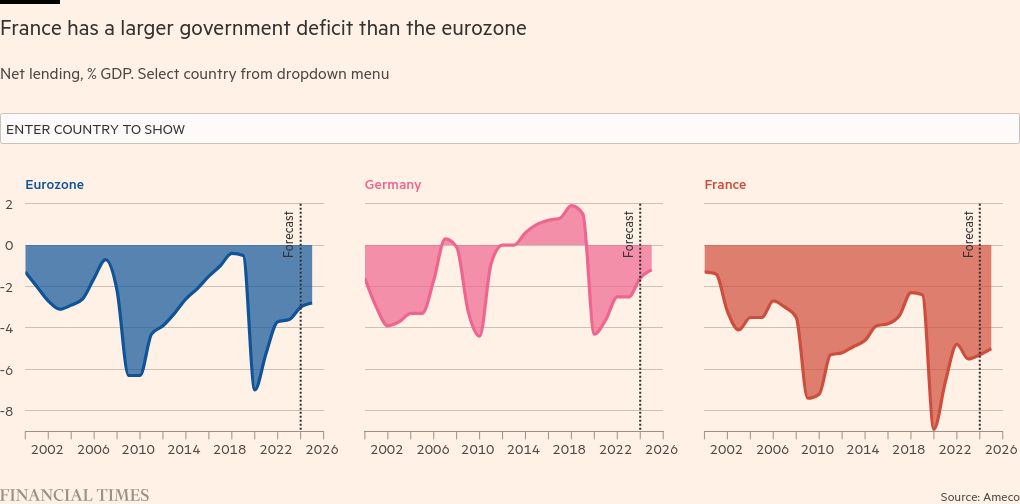

The uncertainty comes at a time of fiscal weakness in France. S&P Global cut its credit rating in May, following a downgrade by Fitch. France is expected to run a budget deficit of 5 percent of GDP next year, down slightly from 5.3 percent this year but still among the highest in the EU and higher than Italy’s, the European Commission said.

France also relies on foreign investors — including a large cohort of Japanese institutions seeking safe havens for European sovereigns — to buy its bonds. While this gives it a more diversified investor base than some, it also makes it more vulnerable to a sharp change in sentiment, analysts say.

Half of France’s government debt is held by non-residents, compared with around 27 percent in Italy and 43 percent in Spain, according to Eurostat data. While Italian households hold 11 percent of the country’s debt, the figure for France is 0.1 percent.

Markets are nervous about what Japanese investors in particular will do, as changes in Japanese monetary policy could make their trades less profitable, according to Tomasz Wieladek, an economist at T Rowe Price.

On June 19, the commission proposed opening an excessive debt procedure for France, as Brussels warned of “high risks” stemming from its analysis of the medium-term sustainability of the debt. The general government debt ratio is on track to rise continuously to around 139 percent of GDP in 2034, it said.

France has so far avoided the kind of crises that Italy and the United Kingdom have experienced in recent years. In 2018, spending plans by Italy’s Five Star-Lega coalition pushed the gap between Italian and German 10-year bond yields to more than 300 basis points, the highest level since the aftermath of Silvio Berlusconi’s premiership, reflecting investors’ assessment of Italy’s political risk.

Analysis by JPMorgan suggests that France could withstand a sudden jump in borrowing costs. A “shock” of 1.5 percentage points higher borrowing costs over two years would only lift the debt-to-GDP ratio to just over 115 percent, marginally above central projections, the bank said in a recent note.

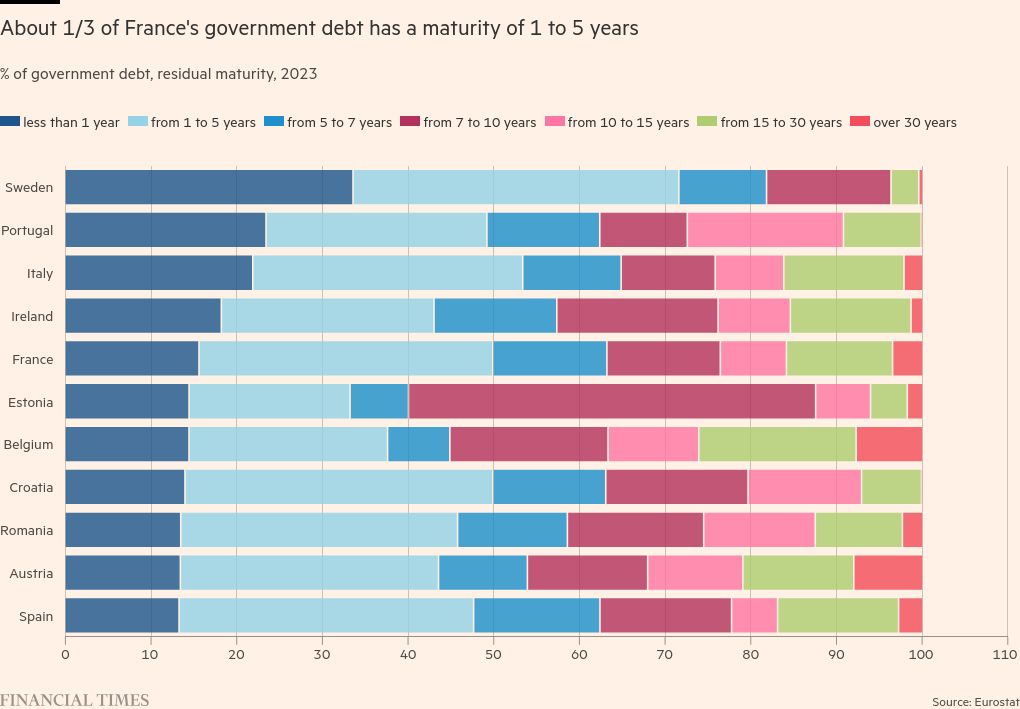

That’s partly because France’s debt stock is relatively long-term, with an average maturity of 8.5 years, according to S&P. That means only 8-10 percent of debt is eligible for refinancing each year, Barclays said, delaying the impact of rising borrowing costs.

“The Liz Truss scenario seems unlikely at this point. I don’t foresee any sudden disruption to French bond markets,” said Holger Schmieding, chief European economist at Berenberg, who predicted that Le Pen’s party would try to be relatively moderate on fiscal policy.

The country’s long-term fundamentals, however, are not good, Schmieding said, especially if France deviates from Macron’s pro-growth policies. A confrontational approach with Brussels is seen as a risk of broader unrest in the EU. Some investors also worry that a broader sell-off of French debt would cause contagion in other European countries, forcing the European Central Bank to intervene.

France’s public debt rose above 115 percent of GDP in 2020, almost double the 2007 level. Last year, the debt-to-GDP ratio was the third-highest in the EU, after Greece and Italy, at 111 percent of GDP.

Against this backdrop, Schmieding pointed to the possibility of higher borrowing costs or further credit rating downgrades, especially if growth slows.

“In the longer term, this is a serious financial problem,” Schmieding said.