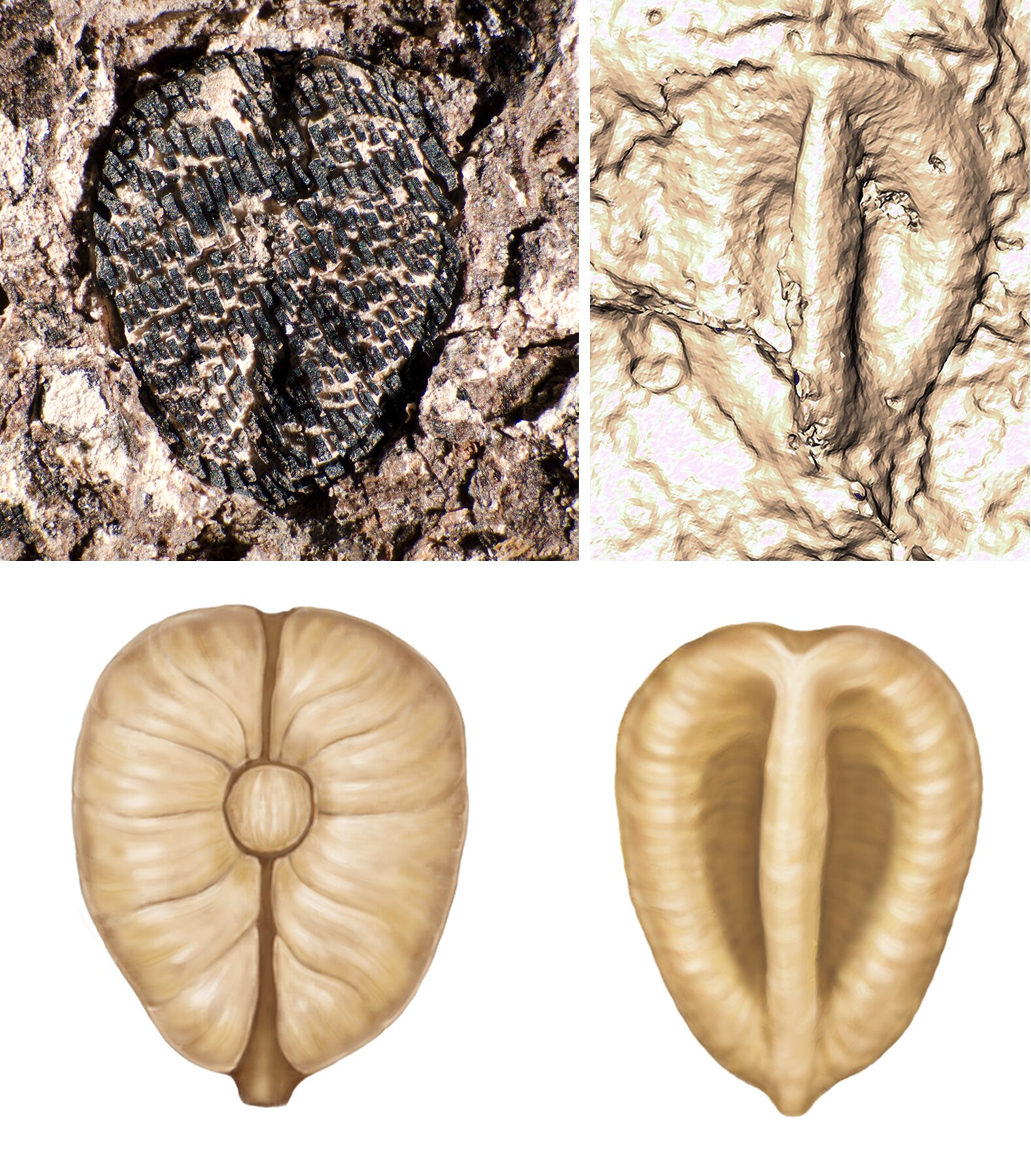

Lithouva – the earliest fossil grape from the Western Hemisphere, ~60 million years old from Colombia. Top image shows fossil accompanied by CT scan reconstruction. Bottom image shows artist’s reconstruction. Credit: Fabiany Herrera, art by Pollyanna von Knorring.

If you’ve ever consumed raisins or enjoyed a glass of wine, you may have partly to thank the extinction of the dinosaurs. In a discovery described in the journal Nature plantsresearchers found fossil grape seeds ranging from 60 to 19 million years old in Colombia, Panama and Peru. One of these species represents the earliest known example of plants from the grape family in the Western Hemisphere. These fossil seeds show how the grape family spread in the years after the death of the dinosaurs.

“These are the oldest grapes ever found in this part of the world, and they are a few million years younger than the oldest grapes ever found on the other side of the planet,” said Fabiany Herrera, assistant curator of paleobotany at the Field Museum at the Negaunee Integrative Research Center in Chicago and the lead author of the paper. “This discovery is important because it shows that grapes really began to spread around the world after the extinction of the dinosaurs.”

It’s rare for soft tissues like fruits to be preserved as fossils, so scientists’ understanding of ancient fruits often comes from the seeds, which are more likely to fossilize. The earliest known grape seed fossils were found in India and are 66 million years old. It’s no coincidence that grapes first appeared in the fossil record 66 million years ago; that’s around the time a massive asteroid hit Earth, triggering a massive extinction event that changed the course of life on the planet.

“We always think about the animals, the dinosaurs, because they were the ones that were most affected, but the extinction also had a huge impact on plants,” Herrera says. “The forest resets itself, in a way that changes the composition of the plants.”

Herrera and his colleagues hypothesize that the disappearance of dinosaurs may have contributed to the change in the forests. “Large animals, like dinosaurs, are known to change their surrounding ecosystems. We think that if large dinosaurs were roaming the forest, they would probably knock down trees, leaving the forests more open than they are now,” says Mónica Carvalho, a co-author of the paper and an assistant curator at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

But without large dinosaurs to prune them, some tropical forests, including those in South America, became more crowded, with layers of trees providing an understory and canopy.

Lead author Fabiany Herrera holds a fossil of the oldest grape ever found in the Western Hemisphere. Credit: Fabiany Herrera

These new, dense forests presented an opportunity. “In the fossil record around this time we start to see more plants that use vines to climb trees, like grapes,” Herrera says. The diversification of birds and mammals in the years after the mass extinction may also have helped grapes by spreading their seeds.

In 2013, Herrera’s Ph.D. advisor and lead author of the new paper, Steven Manchester, a paper that described the oldest known grape seed fossil from India. Although fossil grapes had never been found in South America, Herrera suspected they might be there too.

“Grapes have an extensive fossil record starting about 50 million years ago, so I wanted to discover one in South America, but it was like looking for a needle in a haystack,” Herrera says. “I’ve been looking for the oldest grape in the Western Hemisphere since I was an undergraduate.”

But in 2022, Herrera and his co-author Mónica Carvalho were conducting fieldwork in the Colombian Andes when a fossil caught Carvalho’s attention. “She looked at me and said, ‘Fabiany, a grape!’ And then I looked at it and I thought, ‘Oh my God.’ It was so exciting,” Herrera recalls. The fossil was in a 60-million-year-old rock, making it not only the first South American grape fossil, but also one of the oldest grape fossils in the world.

Mónica Carvalho, co-author of the paper, holds the fossil of the oldest grape seed found in the Western Hemisphere. Credit: Fabiany Herrera

The fossil seed itself is small, but Herrera and Carvalho were able to identify it based on its specific shape, size and other morphological features. Back in the lab, they performed CT scans that showed the internal structure, confirming the identity.

The team named the fossil Lithouva susmanii, “Susman’s stone grape,” in honor of Arthur T. Susman, a proponent of South American paleobotany at the Field Museum. “This new species is also important because it supports a South American origin of the group in which the common vine Vitis evolved,” said co-author Gregory Stull of the National Museum of Natural History.

The team continued fieldwork in South and Central America, and in the Nature Plants paper, Herrera and his co-authors ultimately described nine new species of fossil grapes from Colombia, Panama, and Peru, ranging from 60 to 19 million years old. These fossilized seeds tell the story not only of the spread of grapes across the Western Hemisphere, but also of the many extinctions and dispersals the grape family has undergone.

The fossils are only distantly related to grapes native to the Western Hemisphere, and a few, such as the two species of Leea, are now found only in the Eastern Hemisphere. Their place in the grape family tree indicates that their evolutionary journey has been a tumultuous one.

“The fossil record tells us that grapes are a very resilient order. It’s a group that has suffered a lot of extinction in the Central and South American region, but they’ve also managed to adapt and survive in other parts of the world,” Herrera says.

Given the mass extinction our planet is currently facing, Herrera says studies like this are valuable because they reveal patterns of how biodiversity crises play out. “But what I also love about these fossils is that these small, unassuming seeds can tell us so much about the evolution of the forest,” Herrera says.

This study was conducted by Fabiany Herrera (Field Museum), Mónica Carvalho (University of Michigan), Gregory Stull (National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution), Carlos Jarramillo (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute), and Steven Manchester (Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida).

More information:

Cenozoic seeds of Vitaceae reveal a long history of extinction and dispersal in the Neotropics, Nature plants (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41477-024-01717-9

Quote: Sixty-million-year-old grape seeds reveal how the death of the dinosaurs may have paved the way for the spread of grapes (2024, July 1) Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-sixty-million-years-old-grape-seeds.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair dealing purposes for private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.