On July 9, Anne-Sophie Chassagnou will assess whether the skies are clear enough for Europe to launch its first new rocket in almost 30 years.

The only 26-year-old chief weatherman for the first flight of Ariane 6 has an enormous influence on the continent’s space ambitions. Last year, just minutes before ignition, the meteorologist at the French space agency CNES called off the first attempt to launch Europe’s €1.6 billion mission to explore Jupiter’s icy moons.

“My body was shaking when I had to press the red button,” she said from Europe’s spaceport in French Guiana, between Brazil and Suriname, but if conditions aren’t right for Ariane 6, she won’t hesitate to do it again. “I don’t want to, but if I have to, I will,” she said.

This time, the stakes are much higher than a deep space mission. The first flight of the heavy-lift Ariane 6 rocket will test whether Europe can rebuild its credibility in the commercial launch market once dominated by Ariane 5 and now by Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Europe is also counting on Ariane 6 to restore its independent access to space — an increasingly contested domain where global superpowers fight for economic and strategic supremacy. Over the past year, the bloc has had to rely on SpaceX to launch some of its most sensitive satellites.

It’s an uncomfortable position. In the 1970s, the US tried to prevent some European satellites from competing commercially in exchange for providing launch services. “The Ariane program was initiated because there was no commercial access to space,” said Eric Dalbiès, chairman of ArianeGroup, the French-owned joint venture that produces Europe’s Ariane heavy-lift rockets. “It has reinvigorated the need for Europe to have sovereign access.”

Now Europe once again no longer has its own launch capacity after Ariane 5 was scrapped last July. Technological challenges, pandemic lockdowns and skills shortages caused a costly four-year delay for Ariane 6. Cooperation with Russia ended after the invasion of Ukraine and problems with Italy’s new medium-sized launcher Vega-C have caused that rocket to grounded since 2022.

Josef Aschbacher, head of the European Space Agency, has described the situation as a “crisis” for Europe. The EU’s new space strategy for security and defense made restoring autonomous access to space a priority.

At the Guiana Space Centre, located near the coastal town of Kourou, teams from ESA, CNES and ArianeGroup have been working hard to achieve that goal.

In April, the core of the rocket was transferred to the launch pad and two boosters with 140 tons of solid fuel were attached. On June 20, Ariane 6 was refueled and defueled in the final rehearsal. Sixteen satellites and experiments were loaded onto the rocket.

Nearly 50 percent of rockets fail on their first flight, Aschbacher said, but Kourou officials hope repeated tests and rehearsals have reduced the risks. The focus is on “getting it right the first time,” said Lucia Linares, ESA’s chief strategy officer.

Even if the first flight fails, Europe’s strategic needs will keep the program alive. What is less certain is whether the rocket can compete in a market that has changed radically since Europe opted to build a conventional launch vehicle in 2014.

SpaceX’s reusable Falcon 9 has driven down prices, making it the clear leader for cheap, reliable launches. This week, the EU’s own weather satellite operator opted to launch its next spacecraft on SpaceX, rather than wait for Ariane 6. SpaceX expects Starship, the world’s most powerful rocket, which completed its fourth test flight this month, to also be reusable — unlike Ariane 6.

The European decision not to invest in a reusable rocket is widely seen as a mistake. Germany was reluctant to pay for a new rocket program, according to former ESA chief Jan Wörner. “The German idea was to continue with Ariane 5, but with a new upper stage. This was the cheap solution,” he said.

But France, which has long dominated Europe’s rocket industry, wanted to preserve rocket-building jobs and skills with a new program.

A compromise was reached. ArianeGroup, a merger of the French-German rocket companies Airbus and Safran, promised to design a disposable launcher that was at least 50 percent cheaper to operate than Ariane 5, would fly in five years and would not require subsidies, Wörner said. The program failed on all those counts.

Last fall, ESA member states agreed to invest an additional €1 billion, on top of the estimated €4 billion in development costs, to enable Ariane 6 to compete with SpaceX.

Some experts are defending Europe’s decision to reject reuse in favor of a disposable launcher with a highly flexible upper stage that can carry satellites to different orbits in one mission. A reusable rocket would have required significant, sustained demand that was not available, they say.

“It was the right decision,” Linares said. “It is true that if you reuse the first phase… normally the cost is lower. But it depends on how many times you can launch.”

But even for a conventional rocket, demand matters and the Ariane 6 enters a more difficult commercial market than its predecessor.

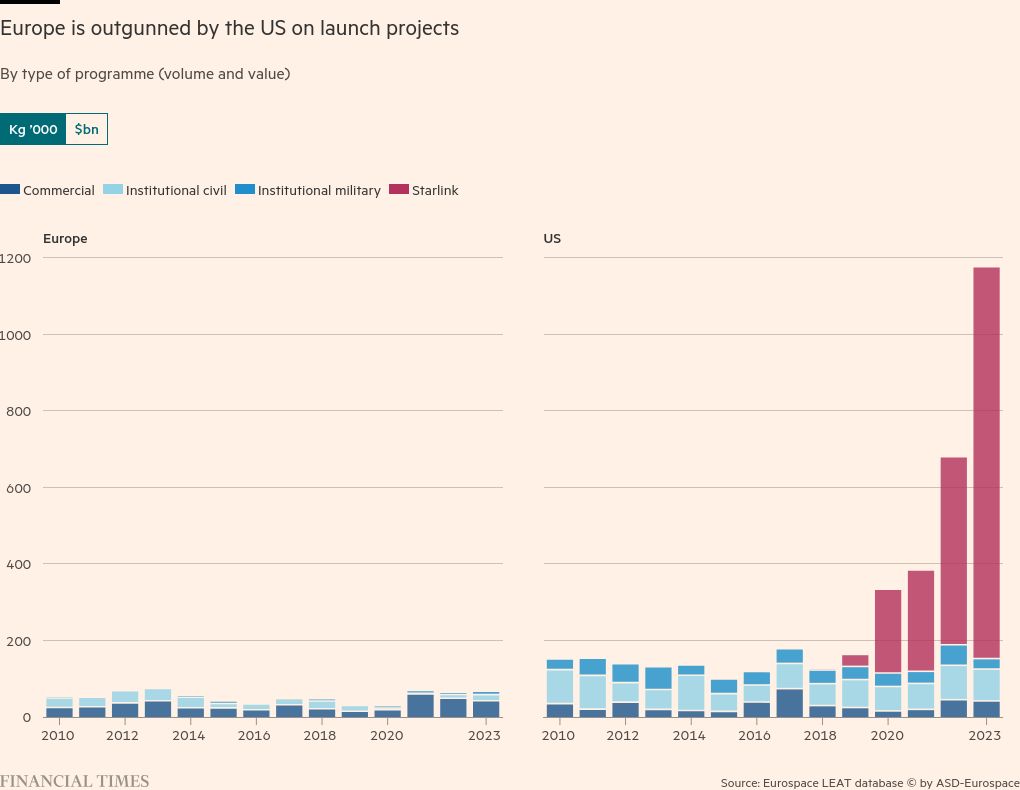

Over the next decade, the US will launch roughly three times as many satellites as Europe for governments, universities and other institutions, and almost ten times as many commercial spacecraft, according to analysts Novaspace. The Pentagon, NASA and Musk’s own Starlink satellite broadband service will likely turn to SpaceX before Ariane.

Meanwhile, a wave of launch vehicle startups around the world are eyeing the booming market for low-Earth orbit satellite services.

“Ariane used to launch two non-institutional satellites for every institutional satellite. But today, new launchers are responding to that demand,” said Pierre Lionnet, head of research at trade association ASD-Eurospace.

Novaspace estimates that around 2,800 satellites will be launched annually through 2033. Much of that activity will be covered by domestic launchers, but Linares thinks there will still be plenty open to competition – and Ariane’s flexibility will be an advantage.

Ariane 6 is already booked for 30 launches, including 18 for Amazon’s upcoming Project Kuiper broadband constellation. Customers want a diversity of launch providers beyond SpaceX, Linares said.

But even those involved in the European programme admit that the system that spawned Ariane 6 – which awards supply contracts based on nationality rather than competitiveness – will have to change. This year, ESA launched a competition to develop small commercial launchers, from which it will buy services.

The move was an “electric shock” to the corporate and political complacency that had dogged Ariane 6, an insider said.

Yet a heavy rocket is so expensive that Europe cannot avoid cooperation and compromises, which could further undermine competitiveness.

“I am not convinced that we can offer launch services in Europe at prices as low as SpaceX,” said Carine Leveau, head of space transportation systems at CNES. “But we can be more competitive than we are now and more than we will be with Ariane 6.”

But for now the priority is ensuring Europe’s access to space. “It is very important that this inaugural flight is a success,” she added. “It will reassure everyone.”

Illustration by Ian Bott