NASA’s Odyssey spacecraft, the longest-running mission to Mars, today completed its 100,000th orbit around the Red Planet, the mission team announced in a press release. rack.

To celebrate the milestone, the space agency has released an intricate panorama of Olympus Mons, the tallest volcano in the solar system; Odyssey captured the view in March. The volcano’s base extends 373 miles (600 kilometers) near the Martian equator, shooting 17 miles (27 kilometers) into the planet’s thin air. Earlier this month, astronomers discovered short-lived morning frost which covers the volcano’s summit for a few hours each day, providing new insights into how ice from the poles circulates through the arid world.

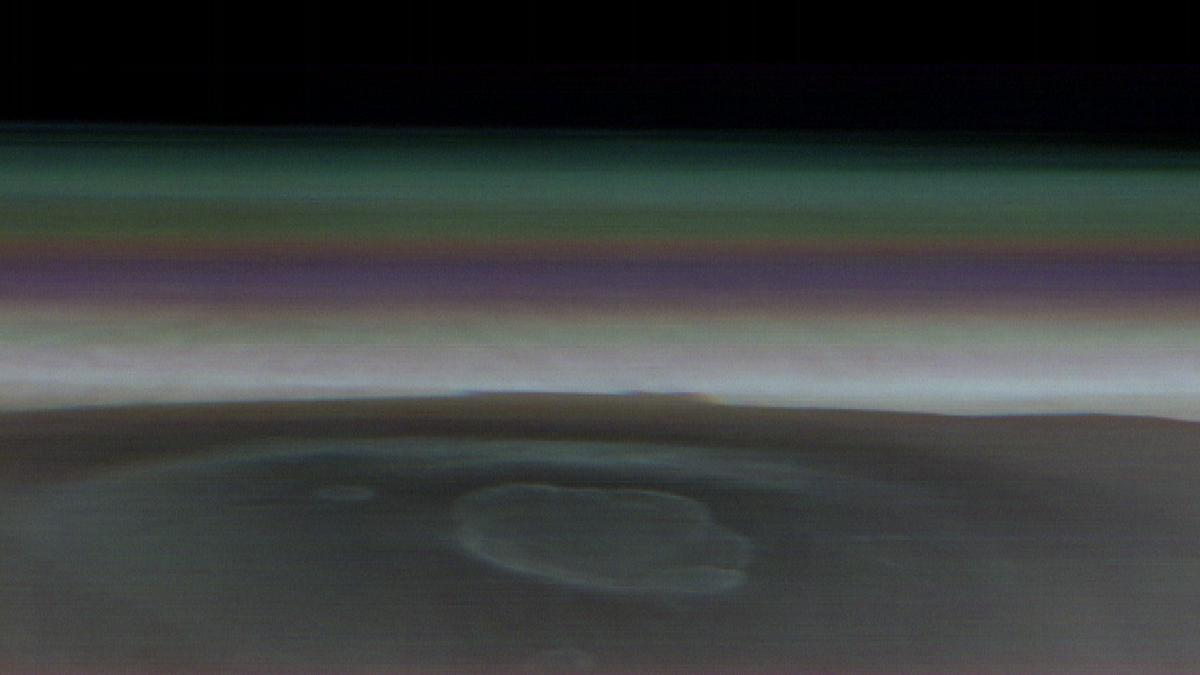

In Odyssey’s latest image of the volcano, the blue-white band seen on grazing Olympus Mons shows the amount of dust floating in the Martian air when the image was taken, NASA said. The thin purple layer just above it likely represents a mixture of atmospheric dust with bluish water-ice clouds. The blue-green layer at the upper edge of the world marks where water-ice clouds extend about 30 miles (48 kilometers) into the Martian sky, scientists said.

To capture the latest panorama, scientists instructed Odyssey to slowly rotate so that its camera was pointed toward the Martian horizon, producing images similar to those taken by residents of the International Space Station.

Related: The gigantic Martian mountain Olympus Mons may have once been a volcanic island

“Normally we see Olympus Mons in narrow strips from above, but by turning the spacecraft toward the horizon we can see in one image how large it towers over the landscape,” said Jeffrey Plaut, Odyssey’s project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory ( JPL) in California, in the recent press release. “The image is not only spectacular, but also provides us with unique scientific data.”

By taking similar images at different times during the year, scientists can study how Mars’ atmosphere changes during the planet’s four seasons, each lasting four to seven months.

Scientists say the groundwork for the latest image began way back in 2008, when another NASA mission called Phoenix landed on Mars. When Odyssey, which served as a communications link between the lander and Earth, pointed its antenna at the lander, scientists noticed that the camera could view the Martian horizon.

“We just decided to turn the camera on and see what it looks like,” said Steve Sanders, who serves as Odyssey’s spacecraft engineer at Lockheed Martin Space in Denver, Colorado. “Based on those experiments, we designed a sequence that will last [the camera’s] field of view centered on the horizon as we travel around the planet.”

The Odyssey mission was launched in April 2001 and is managed by JPL. It was NASA’s first successful mission to Mars after a pair of failures two years earlier. In 1998, the Mars Climate Orbiter was to have appeared Burnt-out in the Martian atmosphere after mission engineers mixed up translations between two measurement systems. A year later, the Mars Polar Lander crashed into the Martian surface due to its engine cuts out abruptly prior to landing. Odyssey was therefore widely seen as a mission of redemption.

Odyssey entered orbit around Mars in October 2001 and has since uncovered previously hidden water-ice reservoirs just beneath the planet’s surface that may be within reach of future Mars astronauts. The spacecraft also mapped large swaths of the planet’s surface, including its craters, which has helped astronomers decipher the history of Mars.

The spacecraft’s recent milestone of 100,000 orbits means it has traveled more than 1.4 billion miles (2.2 billion kilometers). The sun-powered spacecraft doesn’t have a fuel gauge, so the mission team is relying on their mathematical skills to estimate the remaining fuel that will keep the 23-year-old mission going. “The physics does a lot of the heavy lifting for us,” Sanders said. “But it’s the subtleties that we have to manage over and over again.”

Recent calculations suggest Odyssey has about four kilograms of propellant left, enough to keep the legacy mission going until late 2025.

“It takes careful monitoring to keep a mission going for so long while maintaining a historical timeline of scientific planning and execution — and innovative engineering practices,” said Joseph Hunt, Odyssey’s project manager at JPL. “We look forward to collecting more great science in the years to come.”