Painting of a griffin, a chimera of a lion bird of prey, next to the fossils of Protoceratopesa horned dinosaur. The latter would have influenced the lore and appearance of the former, but our study suggests there is no compelling connection between dinosaurs and griffins. Credit: Dr Mark Witton

A new study refutes the theory that inspired griffin myths Protoceratops dinosaur fossils, exposing inconsistencies in the geographical and historical evidence and calling for a return to traditional interpretations of these mythological creatures.

A new study challenges the popular and common claim that dinosaur fossils inspired the legend of the griffin, the mythological creature with the head and wings of a bird of prey and the body of a lion.

The specific connection between dinosaur fossils and griffin mythology was proposed over thirty years ago in a series of articles and books written by folklorist Adrienne Mayor, beginning with the 1989 Cryptozoology article entitled “Paleocryptozoology: A Call for Collaboration between Classicists and Cryptozoologists,” and were codified in the seminal 2000 book “The First Fossil Hunters.” The idea became a staple of books, documentaries and museum exhibits.

It suggests that an early horned dinosaur from Mongolia and China, Protoceratopeswas discovered by ancient nomads searching for gold in Central Asia. Stories of Protoceratops bones then traveled southwest on trade routes to inspire, or at least influence, stories and art about the griffin.

Griffins are among the oldest mythological creatures. They first appeared in Egyptian and Middle Eastern art in the 4th millennium BC. In ancient Greece, they became popular in the 8th century BC.

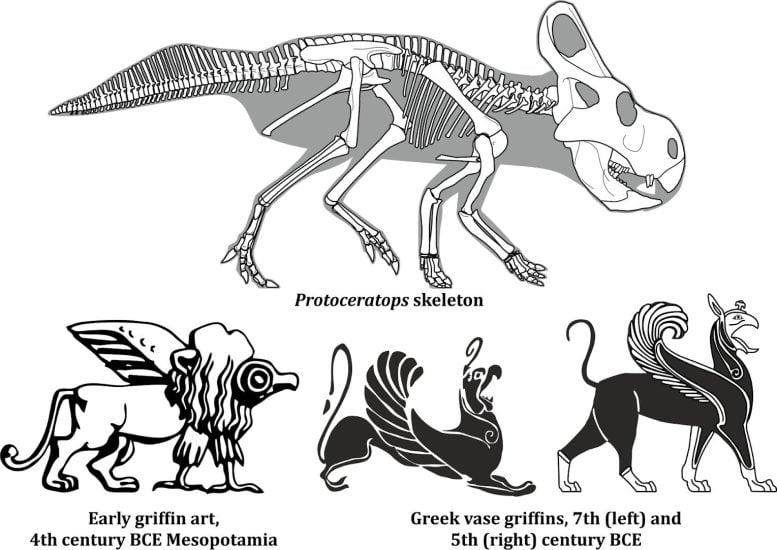

Protoceratops was a small (about 2 meters long) dinosaur that lived in Mongolia and northern China during the Chalk period (75-71 million years ago). They belong to the horned dinosaurs, which makes them related to Triceratops, although they do not actually have facial horns. Like griffins, Protoceratops stood on four legs, had beaks and a kind of collar-shaped skull that, it is claimed, could be interpreted as wings.

Critical reappraisal by scientists

In the first detailed assessment of the claims, study authors Dr. Mark Witton and Richard Hing, paleontologists at New York University, investigated University of Portsmouthre-evaluated historical fossil records, their distribution and nature Protoceratops fossils and classical sources that associate the griffin with the Protoceratopesin consultation with historians and archaeologists to fully understand the conventional, non-fossil view of griffin origins. Ultimately, they concluded that none of the arguments stood up to scrutiny.

Ideas that Protoceratops would be discovered by nomads looking for gold, for example, but it is unlikely when Protoceratopes fossils are found hundreds of kilometers away from ancient gold deposits. In the century since Protoceratops was discovered, no gold has been reported besides them. It also seems doubtful that nomads would have seen much of it Protoceratops skeletons, even if they were looking for gold where their fossils were located.

Comparisons between the skeleton of Protoceratops and ancient griffin art. The griffins are all very clearly based on big cats, from their muscular mass and long, flexible tails to their manes (indicated by the coiled ‘hair’ on the neck) and birds, and differ from Protoceratopes in almost all sizes of proportion and shape. Image compiled from illustrations in Witton and Hing (2024). Credit: Dr Mark Witton

“It is believed that dinosaur skeletons are discovered half-naked and lying around almost like the remains of recently deceased animals,” says Dr Witton. “But generally only a fraction of an eroding dinosaur skeleton will be visible to the naked eye, and unnoticed by all but sharp-eyed fossil hunters.

“That is almost certainly how ancient peoples who roamed Mongolia, Protoceratopes. If they wanted to see more, as they would have to do if they were forming myths about these animals, they would have to extract the fossil from the surrounding rock. That is no easy task, even with modern tools, glue, protective packaging, and preparatory techniques. It seems more likely that Protoceratops Remains generally went unnoticed – if the prospectors were even there to see them.

Alternative explanations for Griffin images

Likewise, the geographical distribution of griffin art through history does not match the scenario of griffin lore beginning with Central Asian fossils and then spreading westward. There are also no unambiguous references to Protoceratopes fossils in ancient literature.

Protoceratops is griffin-like only because it is a four-legged animal with a beak. There are no details in griffin art to suggest that their fossils were referenced, but conversely many griffins were clearly composed of features from living cats and birds.

Dr Witton added: “Everything about the origins of griffins is consistent with their traditional interpretation as imaginary beasts, just as their appearance is fully explained by the fact that they are chimeras of big cats and birds of prey. Invoking a role for dinosaurs in griffin lore, particularly kind from distant lands such as Protoceratopesnot only introduces unnecessary complexity and inconsistencies in its origins, but also relies on interpretations and proposals that do not stand up to scrutiny.”

The authors want to emphasize that there is excellent evidence that fossils played an important cultural role in human history. There are numerous examples of fossils that inspire folklore worldwide, also called ‘geomyths’.

Richard Hing said: “It is important to distinguish between fossil folklore with a factual basis – that is, links between fossils and myths evidenced by archaeological discoveries or compelling references in literature and works of art – and speculated links based on intuition.

“There is nothing inherently wrong with the idea that ancient peoples found dinosaur bones and incorporated them into their mythology, but we must root such proposals in the realities of history, geography and paleontology. Otherwise it’s just speculation.”

Dr Witton added: “Not all mythological creatures require fossil explanations. Some of the most popular geomyths — Protoceratops and griffins, fossil elephants and cyclops, and dragons and dinosaurs – have no evidentiary basis and are entirely speculative. We promote these stories because they are exciting and seem intuitively plausible, but in doing so we ignore our growing knowledge of fossil geomyths, based on facts and evidence. These are just as interesting as their putative counterparts, and probably deserve more attention than completely speculated geomythological scenarios.”

Reference: “Did the horned dinosaur Protoceratops inspire the griffin?” by Mark P. Witton and Richard A. Hing, June 19, 2024, Interdisciplinary scientific reviews.

DOI number: 10.1177/03080188241255543