For some planets, the meteorite bombardment never stops.

A new analysis of data collected by a seismometer on Mars shows that space rocks are hitting the red planet much more often than we ever suspected.

In fact, it looks like Mars is taking a real beating. Based on the number of nearby impact-related tremors detected by the Mars InSight lander during its stay, a team of scientists has estimated that Mars is receiving basketball-sized rocks hitting its surface almost daily.

“This percentage was about five times higher than the percentage estimated from the orbit images alone,” said planetologist and co-lead author Géraldine Zenhäusern of ETH Zurich in Switzerland.

“In line with orbital imaging, our findings demonstrate that seismology is an excellent tool for measuring impact rates.”

Mars InSight revolutionized our knowledge of the red planet in the four years it monitored Mars’ interior until it died in late 2022.

We’d previously thought that Mars was probably pretty boring on the inside; InSight revealed a wealth of tectonic and magmatic activity that had previously escaped our attention, while also revealing the planet’s internal composition.

The other important thing the sensitive laboratory discovered was the weak vibrations of rocks slamming into the Martian crust. This gave scientists a new tool for estimating the impact on Mars, which in turn could help calibrate our understanding of the planet’s geological history.

The rate of cratering on a planetary surface can help gauge how old that surface is. Surfaces with more craters are thought to be older; those with fewer are correspondingly younger. Knowing how quickly those craters appear can help us determine how old a given surface is.

“By using seismic data to better understand how often meteorites hit Mars and how these impacts change the surface, we can piece together a timeline of the red planet’s geological history and evolution,” explains planetologist and co-lead author Natalia Wójcicka of Imperial College London out.

“You could think of it as a kind of ‘cosmic clock’ that helps us date the surface of Mars and perhaps, in the future, other planets in the solar system.”

Here on Earth, thousands of meteors fall every year, but they usually disintegrate high in the atmosphere, while we, the humble Earthlings, are unaware of it. Mars has an atmosphere, but it is more than 100 times thinner than Earth’s. This means that Mars does not have the same protection from impacts; rocks can fall from space almost unhindered.

Furthermore, Mars is very close to the asteroid belt between its orbit and Jupiter’s orbit, so there are many rocks nearby that contribute to a high impact rate.

Previous estimates of the impact rate on Mars have been based on satellite imagery. Satellites orbiting Mars continually take pictures of the surface and record the appearance of new craters. This is an imperfect way to count impacts on its own, but until InSight it was the best option available.

“While new craters are best seen on flat, dusty terrain where they really stand out, this type of terrain covers less than half of the Martian surface,” Zenhäusern explains. “However, the sensitive InSight seismometer was able to hear every single impact within range of the landers.”

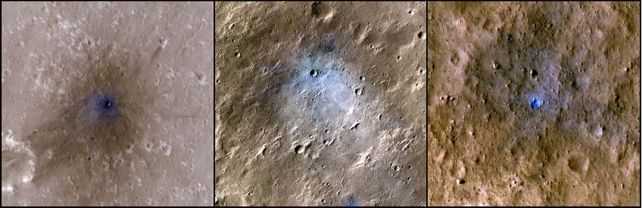

The researchers combined the two sets of data, counting new craters and tracking them to InSight detections. This allowed them to calculate how many impacts had occurred near the lander over the course of a year and extrapolate that to a global impact rate.

It showed that between 280 and 360 impacts occur on Mars every year, creating a crater of more than 8 meters (26 feet) – a rate of about one per day. And about once a month, craters with a diameter of more than 30 meters appear.

Not only is this relevant to understanding the history of Mars, but it also provides valuable information in preparation for human exploration of the red planet.

“This is the first paper of its kind to use seismological data to determine how often meteorites impact the surface of Mars – which was a level one mission objective of the Mars InSight mission,” said seismologist and geodynamic researcher Domenico Giardini of ETH Zurich. “Such data will play a role in planning future missions to Mars.”

The research was published in Nature Astronomy.