In the natural world there are many ways to shine. The best-known type of glow is bioluminescence, in which a chemical reaction takes place in an organism’s body to create light. This is the only way life can glow in complete and utter darkness. But organisms can also glow via fluorescence, a process in which molecules absorb high-energy light and lose that energy by emitting lower-energy light. When high-energy light shines on a molecule, the electrons of that molecule become temporarily excited. And when the molecule relaxes, it emits that excess energy as a photon of longer wavelength light. This is how organisms glow green, red, yellow or orange under higher energy UV light.

To many people, fluorescents may seem like a cool party trick at a roller rink or club, because they often are. But some animals communicate with each other via fluorescence. In the oceans off Japan and South Korea, the affectionately named flower hat jellyfish hunts prey with a fluorescent crown of bright pink and green tentacles. In 2015, researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium noted that young rockfish fish were much more attracted to the jellyfish’s glowing tentacles than to non-fluorescent mimics. And researchers found that birds called parakeets were less interested in mates whose fluorescent feathers were smeared with UV-blocking sunscreen.

Some scientists suggest that this secret communication could also take place on land, between creatures much more closely related to us. In recent years, a group of researchers from Northland College in Wisconsin have discovered that a number of mammals, which look pale brown during the day, fluoresce under black light. These include bright pink flying squirrels and aquamarine platypuses, as Cara Giaimo reported for the New York Times. Curators at the Western Australia Museum began shining a black light on their specimens and found glowing bilbies, hedgehogs, porcupines and echidnas.

The shine was unmistakable. But other researchers remained divided over what it meant. Mammals communicate a lot with the patterns and colors of their fur; a skunk’s stark black-and-white coat warns predators of its noxious odor, and a white-tailed deer’s white flash warns the herd that danger is near. As such, the researchers who discovered this proliferation of fluorescence in mammals suggested that nocturnal or twilight animals may signal each other with their glow. But it’s not entirely clear whether these fluorescent animals can even detect their own fluorescence, especially under the many other light sources in the real world. For example, the bright pink flying squirrels have lost the ability to see the UV light that causes them to glow bright pink. And although our fingernails and teeth fluoresce, we cannot see that fluorescence ourselves.

Now a group of researchers from James Cook University in Australia has put this nocturnal hypothesis to work in the field, in a paper recently published in the Australian Journal of Zoology. They wanted to test whether predators would be more or less attracted to fluorescent rats, which could reveal whether the fluorescence was a way for the rats to camouflage, or if the glow was a way for similar species to communicate with each other.

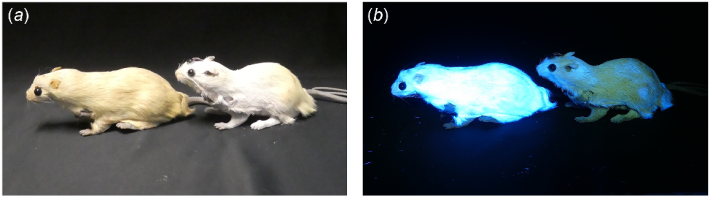

The researchers purchased 36 dead brown rats, whose fur fluoresces whitish blue. They placed the pelts over a plastic rat model (presumably to ensure that the experiments wouldn’t actually be eaten) and sprayed half of them with UV-protected hairspray, then sprayed all the pelts with regular hairspray to make sure they were all smoke the same.

The researchers then placed their model rats in three different locations in the field: an avocado farm, a rainforest bordering a creek, and a forest. At each location, they placed two rat models, one glowing and one not, in front of remote cameras that were activated to record for 20 seconds. The rat models were tethered to the camera to prevent predators from hiding during the experiment, which they often tried to do. The team conducted the experiment on new or full moon nights because previous research showed that full moons triggered scorpions’ natural fluorescence in a way that flying insects could detect.

After watching the videos of test evenings, the researchers found that eleven marsupials, at least nine placental mammal species and four bird species interacted with the rat models. The team recorded which rat model the wild animals interacted with first, as an indication of their preference between the two. Dogs, cats and snouted marsupials, the northern long-nosed bandicoots, interacted with the fake rats at all three locations. Small carnivorous marsupials called quolls were perhaps the animals that interacted most enthusiastically with the rat models, often attempting to drag them away as prey. And although barn owls arrived at the farm only once during a full moon, two seemed to have a standoff over their desired prey.

But across all animals captured on all videos, the researchers found no significant preference for glowing or non-glowing rats. All rat predators and similarly sized species approximated the models with equal probabilities. The team offered two possible explanations for this finding: either that the light from the full moon was not strong enough to evoke the rats’ fluorescence, or that the nocturnal animals simply did not care about fluorescence, even though they could to detect.

Although other researchers had suggested that this fluorescence could provide animals with camouflage in their environment, this group of researchers found little evidence for this line of thinking. In all environments – farm, forest and rainforest – the fluorescent rats showed much more luminescence than the ground below them.

Has this new study solved the mystery of fluorescence? Not quite. Although the researchers did not find any evidence for existing theories about the function of fluorescence, more such studies would be needed for a thorough debunking. It’s safe to say that scientists still don’t understand why this elusive coloration is so widespread among mammals, and what benefit it could possibly provide to furry creatures that scavenge on land. When scientists recently shined UV light on 125 specimens representing more than half of the surviving mammalian families, they found that they all fluoresced, indicating that this kind of glow is not an oddity, but a norm. So the most obvious explanation – that all this fluorescence has no actual function – seems the most likely. After all, would a rat need a reason to glow ethereally at night? Sometimes beauty is a coincidence, a coincidence that we are lucky enough to have learned to see.