Concentrations of ozone-damaging aluminum oxides in Earth’s atmosphere could increase by 650% in the coming decades due to a rise in the number of defunct satellites catching fire during re-entry, a unique study has found. And as mega-satellite constellations continue to pique the interests of private companies, this could be pretty bad news for our planet’s protective shield known as the ozone layer.

The study’s authors say rising concentrations of satellite-generated pollutants could cause “potentially significant” ozone depletion, counteracting the ozone layer’s slow and steady recovery.

The ozone layer must first recover because a hole was created in this layer above Antarctica in the 1980s due to the use of chlorine and fluorine-rich gases in refrigerants and aerosols. However, the gap is mending, thanks to the Montreal Protocol that banned these harmful substances in 1987. But if the team’s new study is correct, this healing process could soon hit a major hurdle due to a new man-made threat: the megaconstellations. In short, megaconstellations are conglomerates of hundreds (sometimes thousands) of individual satellites working together.

During the past years, scientists are beginning to express their concerns about increasing numbers of satellites burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere. Spacecraft bodies are made of aluminum, which when burned produces ozone-destroying aluminum oxides. The new study, conducted by researchers from the University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, is the first to model the formation of these pollutants in the atmosphere and estimate the evolution of their concentrations based on the predicted proliferation of satellites.

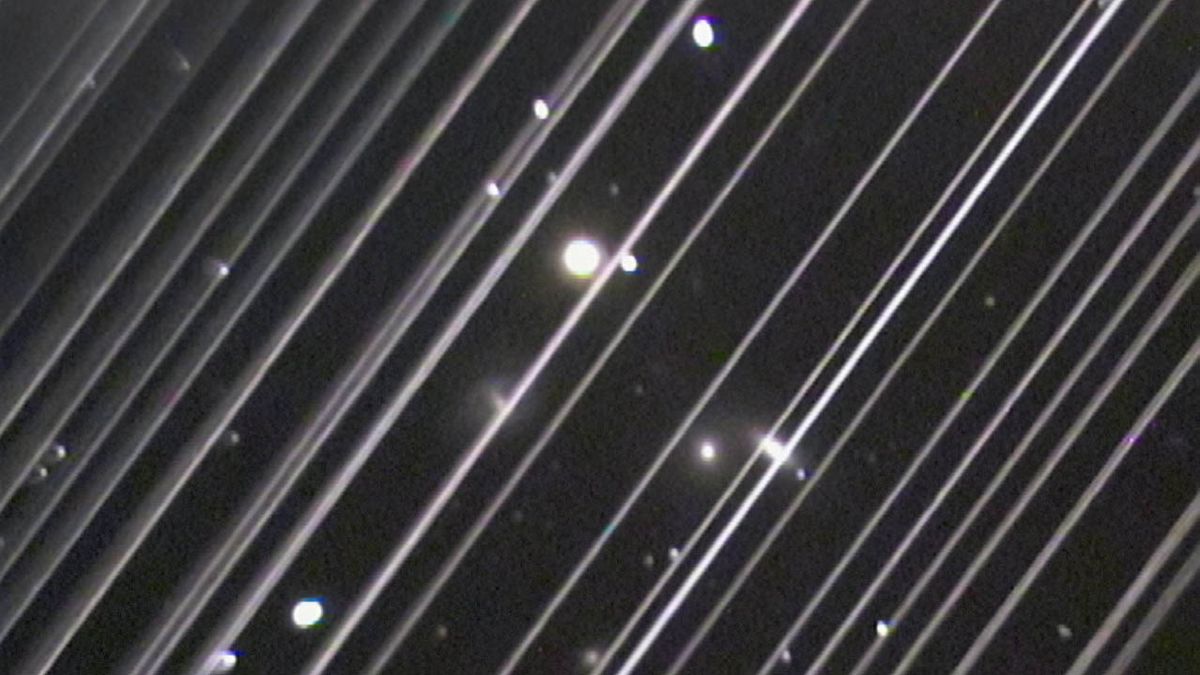

Related: Blinded by the light: how bad are satellite megaconstellations for astronomy?

“This study used an atomic-scale molecular dynamics simulation to quantify the amount of alumina generated during the reentry of a model satellite. The number of satellites reentering the atmosphere for mega-constellations of satellites was then used to predict the amount of alumina that will be generated in the future,” Joseph Wang, professor of Aerospace, Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering at USC and corresponding author of the study, told Space.com.

The researchers found that about 332 tons of old satellites burned up in the atmosphere in 2022, releasing 17 tons of aluminum oxide particles. Between 2016 and 2022, concentrations of these oxides in the atmosphere increased eightfold and will increase further with the growing number of launched and re-entering satellites.

According to the European Space AgencyThere are currently approximately 12,540 satellites in orbit around Earth, of which about 9,800 are operational. By the end of this decade, that number could increase tenfold due to plans by private companies to build mega-constellations of tens of thousands of internet-beaming satellites in low Earth orbit. SpaceX’s Starlink mega-constellation, for example, currently includes more than 6,000 spacecraft, and the company plans to deploy up to 40,000 satellites in total in this endeavor. Companies like OneWeb, Amazon, and the Chinese projects G60 and Guowang are developing their own mega-constellations.

If all these plans come to fruition, as much as 3,200 tons of satellite bodies could burn up in the atmosphere every year by 2030. As a result, 630 tons of aluminum oxides could be released into the upper atmosphere per year, the researchers estimate, leading to a 650% increase in the concentrations of those particles compared to natural levels.

Wang said it takes up to 30 years for the particles, which first accumulate at an altitude of about 85 kilometers, where most satellite material evaporates, to reach the altitudes where the ozone layer is located. Only then would the oxides begin their destructive work. The researchers did not study the impact on the protective ozone shield in detail. However, they did emphasize that the effects could be “significant.”

Most of the planet’s protective ozone is concentrated in the stratosphere at an altitude between nine and 28 miles (15 and 30 km). The ozone absorbs harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation and protects living organisms on the Earth’s surface from damage.

Unlike traditional ozone-depleting substances, aluminum oxide particles trigger ozone destruction processes without being consumed in the reactions, the researchers said. The concentrations of these substances therefore remain stable, allowing the oxides to do so Get on their harmful work, until they naturally descend to lower altitudes below the ozone layer. However, that could also take up to 30 years, Wang said.

Although far more meteorite material than artificial satellites enters the Earth’s atmosphere every year, this natural space rock does not contain aluminum and therefore poses no risk to the ozone layer. The researchers said more research is needed to fully understand the risks that mega-constellations pose to our planet.

“The chemistry and physics of these byproducts that re-enter as they cool and settle in the atmosphere, including chemical reactions with ozone, are not the subject of this study and are not fully understood by the community,” José Pedro Ferreira, a researcher at USC and lead author of the study, told Space.com in an email. “For that reason, any conclusions regarding environmental impacts are premature. These known unknowns should act as an incentive to devote more resources to this line of research, which is currently being pursued by our group at USC.”

The study was published June 12 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.