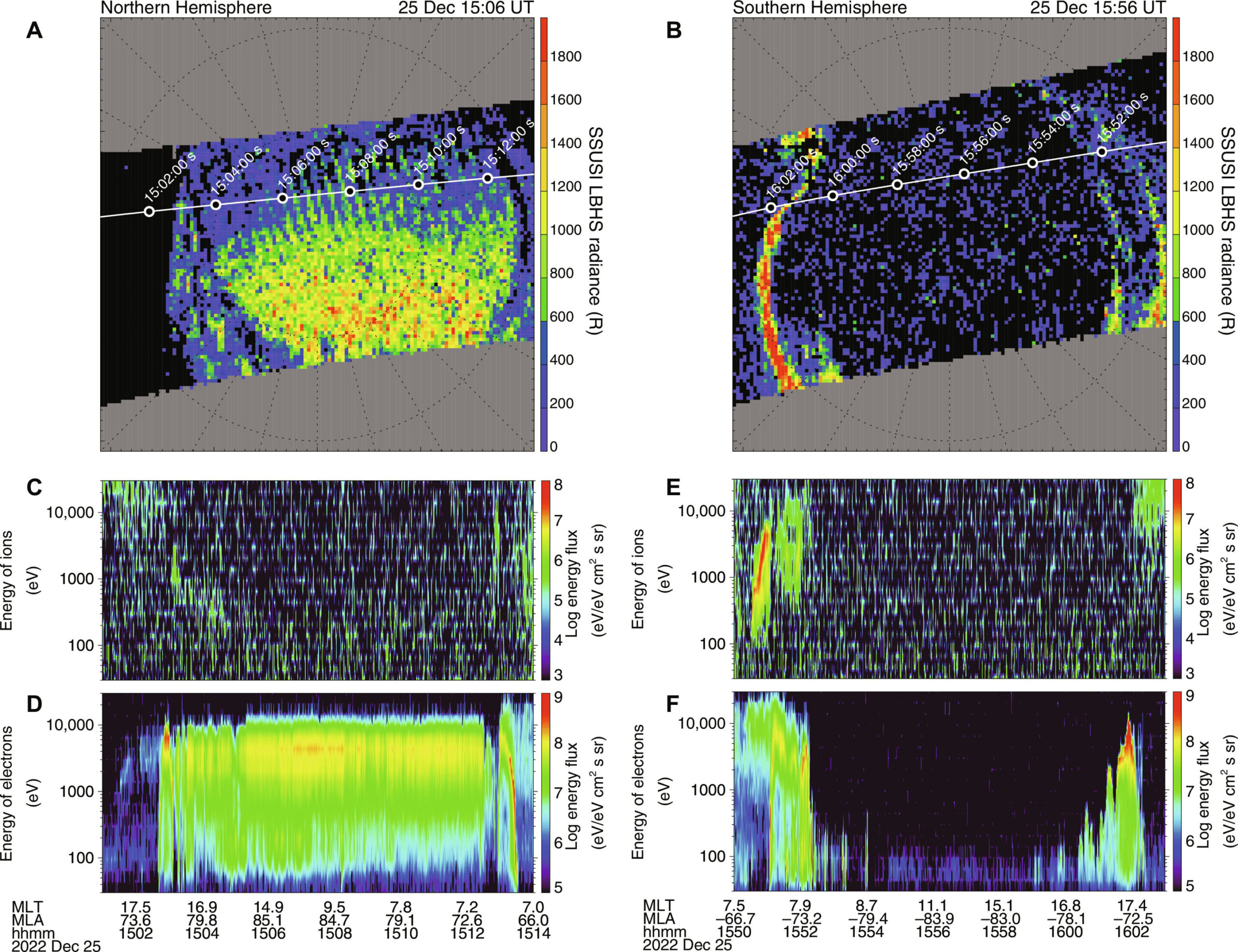

Optical and particle observations by the DMSP satellites in both hemispheres. (A) UV image of the SSUSI on board the DMSP F17 satellite in the Northern Hemisphere (B) UV image of the SSUSI on board the DMSP F17 satellite in the Southern Hemisphere (C and D) Energy-time spectrogram of ions (C) and electrons (D) taken by the particle instruments on board the DMSP F17 satellite during the interval plotted in (A). (E and F) Energy-time spectrogram of ions (E) and electrons (F) taken by the particle instruments on board the DMSP F17 satellite during the interval plotted in (B). Credit: Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn5276

× close to

Optical and particle observations by the DMSP satellites in both hemispheres. (A) UV image of the SSUSI on board the DMSP F17 satellite in the Northern Hemisphere (B) UV image of the SSUSI on board the DMSP F17 satellite in the Southern Hemisphere (C and D) Energy-time spectrogram of ions (C) and electrons (D) taken by the particle instruments on board the DMSP F17 satellite during the interval plotted in (A). (E and F) Energy-time spectrogram of ions (E) and electrons (F) taken by the particle instruments on board the DMSP F17 satellite during the interval plotted in (B). Credit: Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn5276

A small team of astronomers from several institutions in Japan, working with some colleagues in the US, have solved the mystery of the unusually smooth aurora that appeared in the Arctic sky in December 2022.

In their article published in Science progress, The group describes how they delved into both ground data and satellite observations captured during the event, and what they learned along the way.

In December 2020, a ground-based camera in Norway captured what was described at the time as a remarkable aurora event in the night sky – an event that stretched 4,000 kilometers across the polar ice cap. It was considered unusually smooth and covered much more of the night sky than normal.

For two years the source remained a mystery. In this new study, the research team has finally determined the circumstances that led to the unusual event.

The team studied camera images of the event and then compared them with satellite images from 75 degrees of magnetic latitude. In doing so, they found a suprathermal flow of electrons emanating from the Sun’s corona, in emission patterns that were remarkably similar to images captured from polar rain aurorae – where electrons traveling from the Sun’s corona through Earth’s atmosphere above travel the sun. of the polar regions.

Convinced they were on to something, they did some more research, this time into why the aurora could last so long. They discovered that the unique event had occurred during an unusually calm period of solar wind.

As the polar rain aurora filled the night sky in December, solar wind density dropped to just 0.5 cm-3– something that almost never happens. The research team notes that polar rain aurorae are typically invisible to the naked eye. The reason the 2022 event could be seen by a regular camera was the lack of solar wind.

It has been noted that aurora research has been greatly assisted by citizen scientists; for example, they played a key role in solving the source of purple light that appeared over the Canadian sky in 2016.

More information:

Keisuke Hosokawa et al., Exceptionally gigantic aurora in the polar cap on a day when the solar wind almost disappeared, Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adn5276

Magazine information:

Scientific progress

© 2024 Science X Network