It’s funny how things you think are bad sometimes turn out to be good. Like many of us, I was fascinated by all kinds of science as a child. As I got older I focused a little more, but that would come later. Living in a small town, there weren’t many recent books on science and technology, so you tended to read the same books over and over again. One day my library received a copy of the relatively recent book ‘The Amateur Scientist’, a collection of [C. L. Stong’s] Scientific American columns of the same name. [Stong] was an electrical engineer with broad interests, and those columns were great. The book only contained a snapshot of the projects, but they were great. Of course, the magazine had other projects, most of which were beyond my budget and even more beyond my skillset at the time.

If you clicked on the links you probably went down a very deep rabbit hole, so… welcome back. The book was published in 1960, but the projects largely date from the 1950s. The 57 projects ranged from building a telescope – the original topic of the column before it [Stong] took over – to use a bathtub to study the aerodynamics of model airplanes.

X-rays

However, there were two projects that fascinated me and – luckily for me – I didn’t even come close to completing them. One of them was for building an X-ray machine. Called an amateur [Harry Simmons] had described his setup and complained that in 23 years he had never met anyone else who had x-rays as a hobby. Strangely enough, at that time it was not a problem for the magazine to publish his home address.

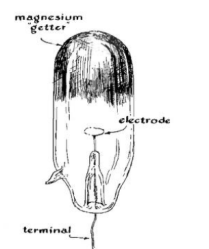

You needed a few things. An Oudin coil, somewhat like a Tesla coil in an autotransformer configuration, generated the necessary high voltage. In fact, it was the Ouidn coil that started the whole thing. [Harry] used it to power a UV light to test minerals for fluorescence. Out of idle curiosity, he replaced the UV lamp with an 01 radio tube. These old tubes had a magnesium coating – a getter – that absorbs the gas that remains in the tube.

The tube glowed inward [Harry’s] hand and it reminded him of what an old gas-filled X-ray tube looked like. He grabbed some film and was able to get an image of screws embedded in a block of wood.

But even then, 01 tubes were difficult to obtain. So [Harry]what we would now call a hacker took the obvious step of having a local glassblower make custom tubes to his specifications.

Living where the library published few books after 1959, it is no surprise that I had no access to 01 tubes or glassblowers. It was also not clear whether he was evacuating the tubs or if the glassblower was doing it for him, but the tube still contained only 0.0001 millimeters of mercury.

Why did this interest me as a child? Don’t know. Why do I care now anyway? If I had the time, I would build one today. We’ve seen more than one DIY x-ray tube project, so it’s doable. But today I am probably able to work safely with high voltages and high vacuums and protect myself from X-rays. Probably. But maybe I still shouldn’t build this. But at 10 years old, I would definitely have done something bad to myself or my parents’ house, if not both.

Then it gets worse

The other project I couldn’t stop reading about was a “homemade atom smasher” developed by [F. B. Lee]. I don’t know about “nuclear crackers,” but they were linear particle accelerators, so I think that’s an accurate description.

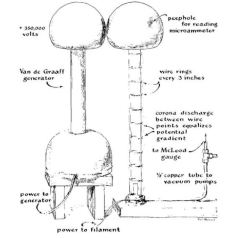

I doubt I have the chops to pull this off today, much less then. Old refrigeration compressors were run backwards to pull a rough vacuum. A homemade mercury diffusion pump got you the rest of the way there. I would work with some of these things later in life with scanning electron microscopes and similar instruments, but I bought them, and not by assembling them from light bulbs, refrigerators and homemade blown glass!

You also needed a good way to measure low pressure, so you had to build a McLeod gauge full of mercury. The accelerator itself is a meter-long tube of borosilicate glass with a diameter of five centimeters. At the top is a metal sphere with a peephole in it so you can see a neon lamp to assess the current in the electron beam. There is a filament at the bottom.

The globe at the top corresponds to that of a Van de Graf generator that generates approximately 500,000 volts at a relatively low current. The particle accelerator is definitely linear, but of course all cool particle accelerators these days form a loop.

[Andres Seltzman] built something similar several years ago, although not quite the same, and you can see it working in the video below:

What can go wrong? High vacuum, mercury, high voltage, an electron beam and many unintended X-rays. [Lee] mentions the danger of “water hammer” in mercury tubes. In addition, [Stong] Apparently he felt nervous enough to get a second opinion from [James Bly] who worked for a company called High Voltage Engineering. He said in part:

…we are somewhat concerned about the dangers associated with it. We wholeheartedly agree with his comments on the dangers of glass breakage and the use of mercury. However, we strongly believe that there is insufficient discussion about the potential dangers posed by X-rays and electrons. Although the researcher is limited to targets with a low atomic number, high-energy X-ray generation will inevitably occur when using electrons with an energy of 200 to 0.300 kilovolts. If currents as high as 20 microamps are reached, we are confident that the resulting hazard is far from negligible. In addition, there will be significant amounts of scattered electrons, some of which will inevitably pass through the observation hole.

I’ve survived it

Obviously I haven’t built either one because I’m still here. I managed to make an arc furnace from a long forgotten book. Curtain rods held carbon rods from some D cells. The fishing rods were in a flower pot full of sand. An old power cord was attached to the curtain rods, although one conductor went through a pot of salt water, creating a resistor so you didn’t blow the fuses.

Somehow I survived without dying from the fumes, blinding myself, or burning myself, but my parents’ house had a burn mark on the floor for years after that experiment.

If you want to build an electric arc furnace, we start with a more modern concept. If you want a safer old book to read, try that of [Edmund Berkeley]the developer of the Geniac.