Early humans appear to have experienced sudden and rapid technological progress about 600,000 years ago, according to new findings from a team of anthropologists who examined the use of ancient stone tools.

The researchers behind the findings say this likely represents a major turning point in ancient human development, where the transmission of ancient knowledge from generation to generation, known as cumulative culture, resulted in increasing advances in society that accelerated biological, cultural and technological development of humanity.

“Our species, Homo sapiens, has managed to adapt to ecological conditions – from tropical forests to Arctic tundra – that require solving different types of problems,” said Associate Professor Charles Perreault, an anthropologist from the School of Human Evolution at Arizona State University. and social change. and a research scientist at the Institute of Human Origins. “Cumulative culture is critical because it allows human populations to build on and recombine the solutions of previous generations and to develop new complex solutions to problems very quickly.”

Tool making suddenly underwent rapid technological progress

In their published study “3.3 million years of stone tool complexity suggests that cumulative culture began during the Middle Pleistocene,” which appeared in the journal PNAS, Perreault and co-author Jonathan Paige, an anthropologist from the University of Missouri, from how their analysis of stone tools dating back 3.3 million years ago revealed this sudden and unexpected technological leap.

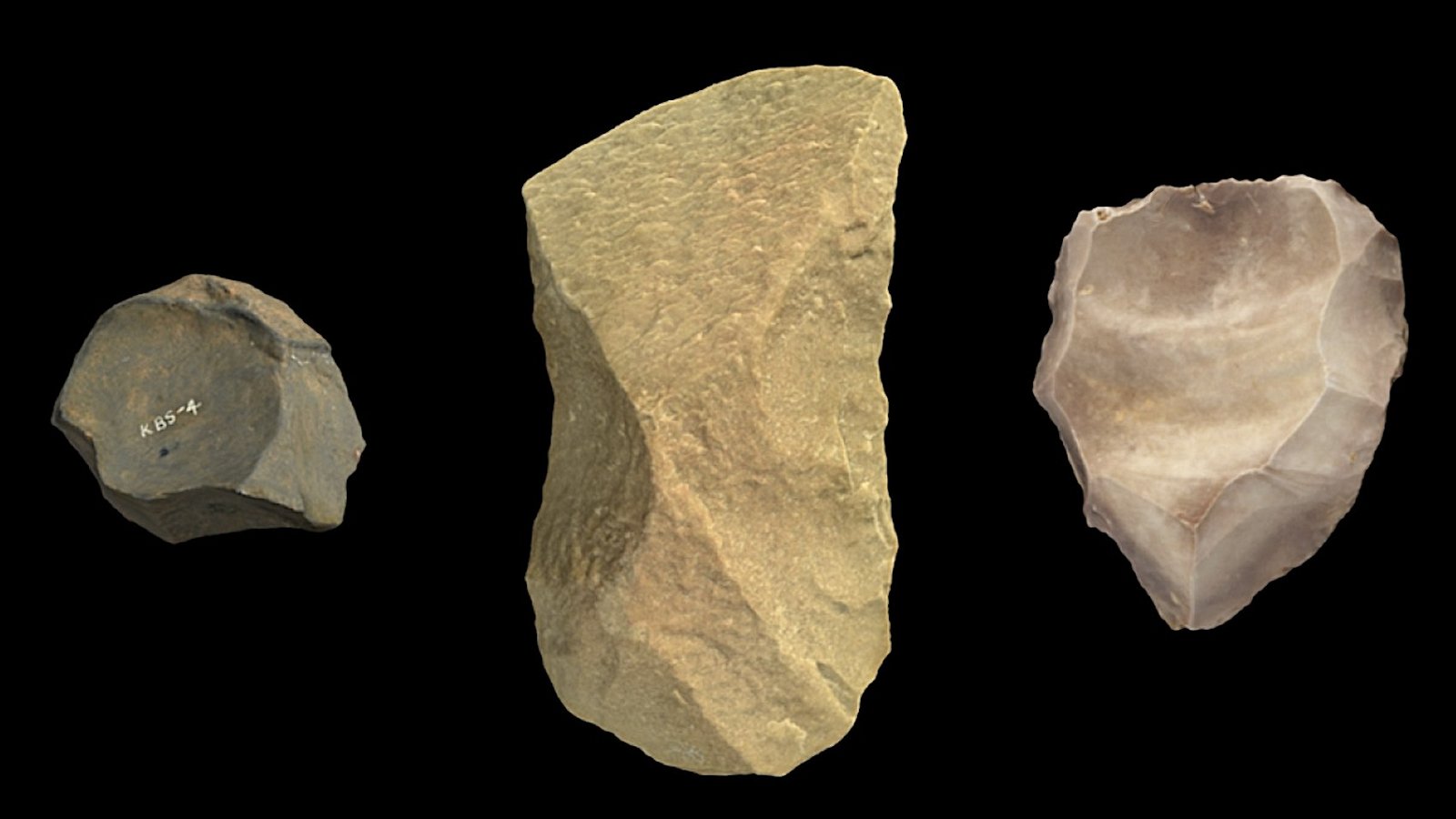

The researchers analyzed tools collected from 57 separate ancient hominin sites. The oldest tool, which is more than 3 million years old, came from an African site. However, the researchers also studied ancient stone tools discovered at ancient hominin sites in Eurasia, Greenland, Sahul, Oceania and the Americas.

The team then ranked the complexity of the tools. This meant that we had to analyze how many steps needed to be taken to create the tool in question. The researchers characterized and ranked 62 different tool-making sequences.

After mapping the complexity of the tools, the team noticed some unexpected patterns. Tools made between 3.3 million years ago and 1.8 million years ago required between two and four procedural units to manufacture. The complexity of stone tools increased steadily over the next 1.2 million years, with the top samples requiring as many as seven steps. Although significantly more complex than tools made more than a million years earlier, the researchers say this is still within the range of complexity for a single craftsman. This means that the knowledge of previous generations of toolmakers was most likely not passed on during that period.

However, the researchers found that when they looked at tools made about 600,000 years ago, in the Middle Pleistocene, they began to see a sudden and unexpected increase in complexity. Tools from this period were not only more complex, but they also required more complex manufacturing processes to make these tools.

“We analyzed the stone tools made over the past 3.3 million years,” the researchers explain. “We found that these stone tools remained simple until about 600,000 years ago. Thereafter, stone tools rapidly increased in complexity.”

While earlier tools required only a handful of procedural steps to manufacture, tools from this era often required as many as 18 steps. According to Paige and Perreault, these are far too many steps for a single generation of artisans to accomplish without the knowledge passed down from previous generations.

This evidence, the researchers write, is consistent with findings from other research teams, suggesting that such a rapid transition “signals the development of a cumulative culture in the human lineage.”

“Around about 600,000 years ago, hominin populations began to rely on unusually complex technologies, and even after that time we see a rapid increase in complexity,” says Paige. “Both findings are consistent with what we expect to see among hominins that rely on cumulative culture.”

The beginning of cumulative culture and the evolution of modern man

While the evolution of stone tool making provides evidence for the emergence of a cumulative culture, the researchers behind the findings say such a leap likely influenced all aspects of early humans. This likely included changes in human culture, biology, and even the ability to adapt to a range of environments and habitats around the world.

“Human dependence on cumulative culture may have shaped the evolution of biological and behavioral traits in the hominin lineage,” Paige and Perreault explain, “including brain size, body size, life history, sociality, subsistence, and ecological niche expansion.”

Such changes may increase in complexity as genetic and cultural evolution occur simultaneously. According to the researchers, this “gene culture co-evolution process” may explain increases in relative brain size, longer life histories, “and other important traits underlying human uniqueness.”

In particular, the researchers point out that the Middle Pleistocene shows many more examples of evolving technology. For example, studies from this era reveal consistent evidence of the controlled use of fire, hearths, and other domestic spaces. This era also marks the evolution of wooden structures built with tree trunks carved using handled tools, which, the researchers explain, are “stone blades attached to wooden or bone handles.”

In their conclusion, Paige and Perreault note that tool making is only one measure of cumulative culture, and that further research could uncover other increases in this behavior that may have occurred in the past but are not immediately apparent in the archaeological archive. “It is possible that early hominins depended on cumulative culture to evolve complex social, foraging, and technological behaviors that are archaeologically invisible,” they write.

Ultimately, the research team believes that their findings show how knowledge can be passed down from generation to generation without each successive generation having to rediscover past knowledge. When enough knowledge comes through, as what appears to have happened 600,000 years ago, this process can result in an ever-expanding and adaptive knowledge pool that allows for consistent upward progress in cultural and technological evolution.

“Generations of improvements, adjustments and fortunate mistakes can produce technologies and knowledge far beyond what a single naive individual could independently invent in a lifetime,” the researchers concluded. “When a child inherits the culture of her parents’ generation, she inherits the result of thousands of years of lucky mistakes and experiments.”

“The result is that our cultures – from technological problems and solutions to the way we organize our institutions – are too complex for individuals to figure out on their own,” Perreault adds.

Christopher Plain is a science fiction and fantasy novelist and chief science writer at The Debrief. Follow him and connect with him X, Learn more about his books at plainfiction.com, or email him directly at christopher@thedebrief.org.