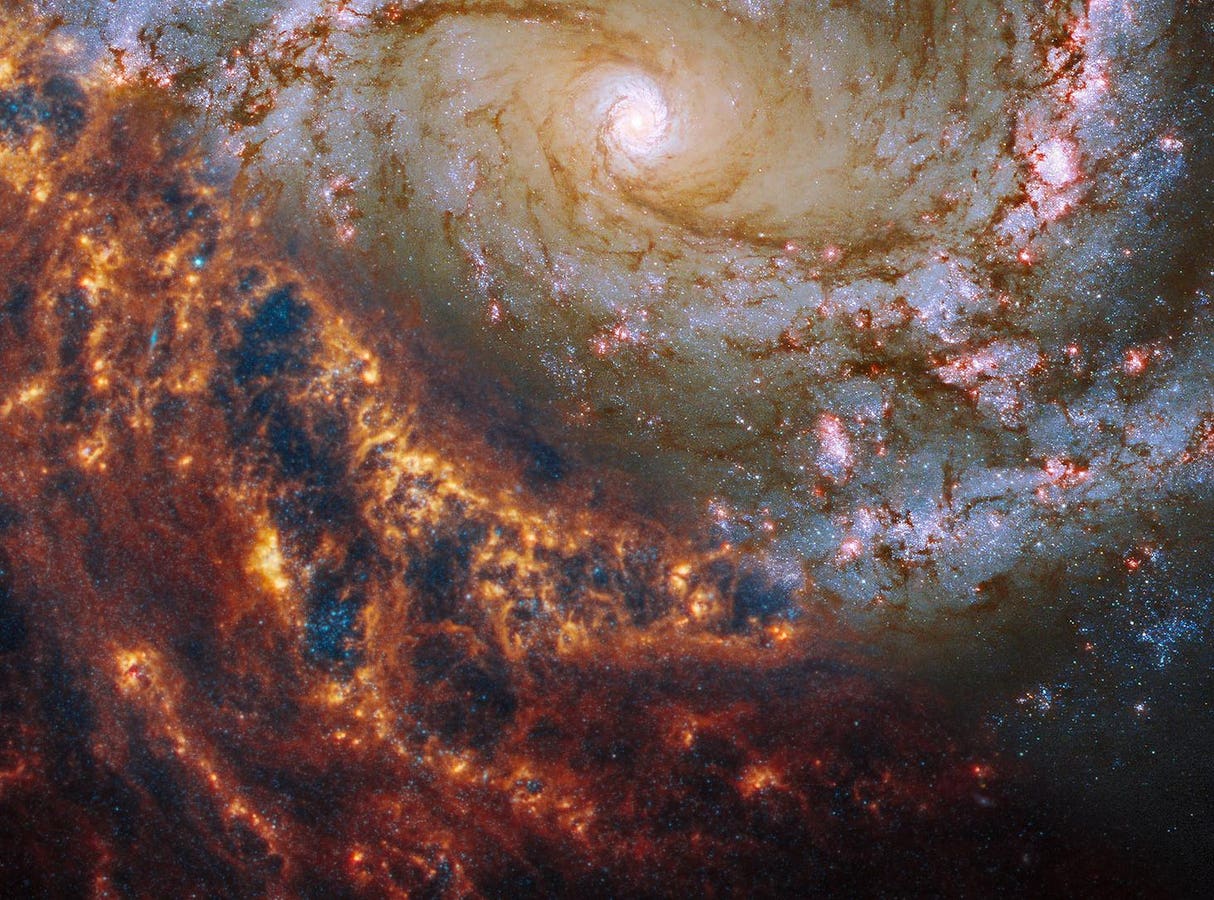

Spiral galaxy, NGC 4303, seen from above. Pink, orange and red galactic long-range images. Elements … [+]

Like most good science, large telescopes often create more riddles than they solve. That’s certainly been the case with NASA’s Webb Space Telescope, whose early deep-sky observations have continually pushed back the era of galaxy formation to ever earlier times and ever higher redshifts.

What is now clear is that there is something wrong with current theories of cosmology.

In yet another series of deep-sky observations with the Webb Space Telescope, a team led by the University of Missouri has found an unexpected abundance of spiral galaxies, which have thin disks and were present some two billion years after the Big Bang itself.

In an article published in The astrophysical diary letters, a team of researchers at the University of Missouri in Columbia, used NASA’s Webb Telescope to make observations of some of the earliest spiral galaxies ever discovered. They were astonished to discover that these early galaxies were not only more common than previously thought, but that they had already developed fully formed spiral arms and disks, similar to what we find in our own Local Group of galaxies.

Our work suggests that spiral galaxies formed several billion years earlier than previously thought, Vicki Kuhn, lead author of the paper and a graduate student in astronomy at the University of Missouri, told me via email.

The Missouri team found that nearly 30 percent of observed galaxies had developed a spiral structure within the universe’s first two billion years. Not only did galaxy formation happen much faster than ever thought possible, but the old paradigm that most spiral galaxies developed about halfway through the universe’s current epoch will likely have to be revised.

The team used Webb’s Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey (CEERS) to visually identify spiral galaxies, the authors note. Of the 873 galaxies, 216 turned out to have a spiral structure, they write.

Some of the spiral galaxies studied by the researchers in the study.

We’re using just one small region of the sky surveyed by the CEERS program, Yicheng Guo, an astronomer at the University of Missouri and one of the paper’s co-authors, told me via email. It’s a part of the sky comparable to the head of a pin held with an arm jump, Kuhn says.

That’s a mind-boggling little slice of observational heaven. So, as Guo is quick to point out, it could be pure luck that the team was able to see these early spiral galaxies at such early times in the cosmos.

Discs make the Milky Way

Our Milky Way is a disk galaxy with spiral arms; it’s a “thin” disk, Guo says. People used to believe that disks in the early universe were thick and that these thick disks first had to become thin disks, he says. And then form spiral arms in it, says Guo. But our work suggests that thinning and spiral arm formation all happened at the same time in the universe’s first few billion years, he says.

What lies ahead?

The Webb is expected to make larger and deeper observations to complement the Missouri team’s analysis of high-redshift spiral galaxies, the team notes in their paper.

What is the most puzzling?

The percentage of spiral galaxies we see is surprisingly flat over much of cosmic time, from two billion years after the universe formed to about seven billion years after the Big Bang, Guo says.

This means that the beginning of spiral formation occurred even earlier than when the universe was 2 billion years old, he says. This means that even with the Webb telescope, we have not yet explored the actual origins of spiral galaxies in the universe, Guo says.

A reconsideration

So we may need to rethink our understanding of galaxy formation, Kuhn says.