To be honest, I believe in a future of space colonization because I want to believe in it. It’s romantic. It’s adventurous. It is cool! At worst, it is also the way to preserve the species in case we ruin the Earth deus ex humana to save ourselves, even though we might not deserve it under those circumstances. I support the Artemis missions and the Gateway project, which could begin construction of a space station in lunar orbit by the end of this decade, and a manned mission to Mars within my lifetime. I dream of what lies beyond, because it is good and healthy to dream. Standing in the way are numerous technological hurdles, which in themselves are worth tackling: we make scientific progress by determining which challenges can be overcome.

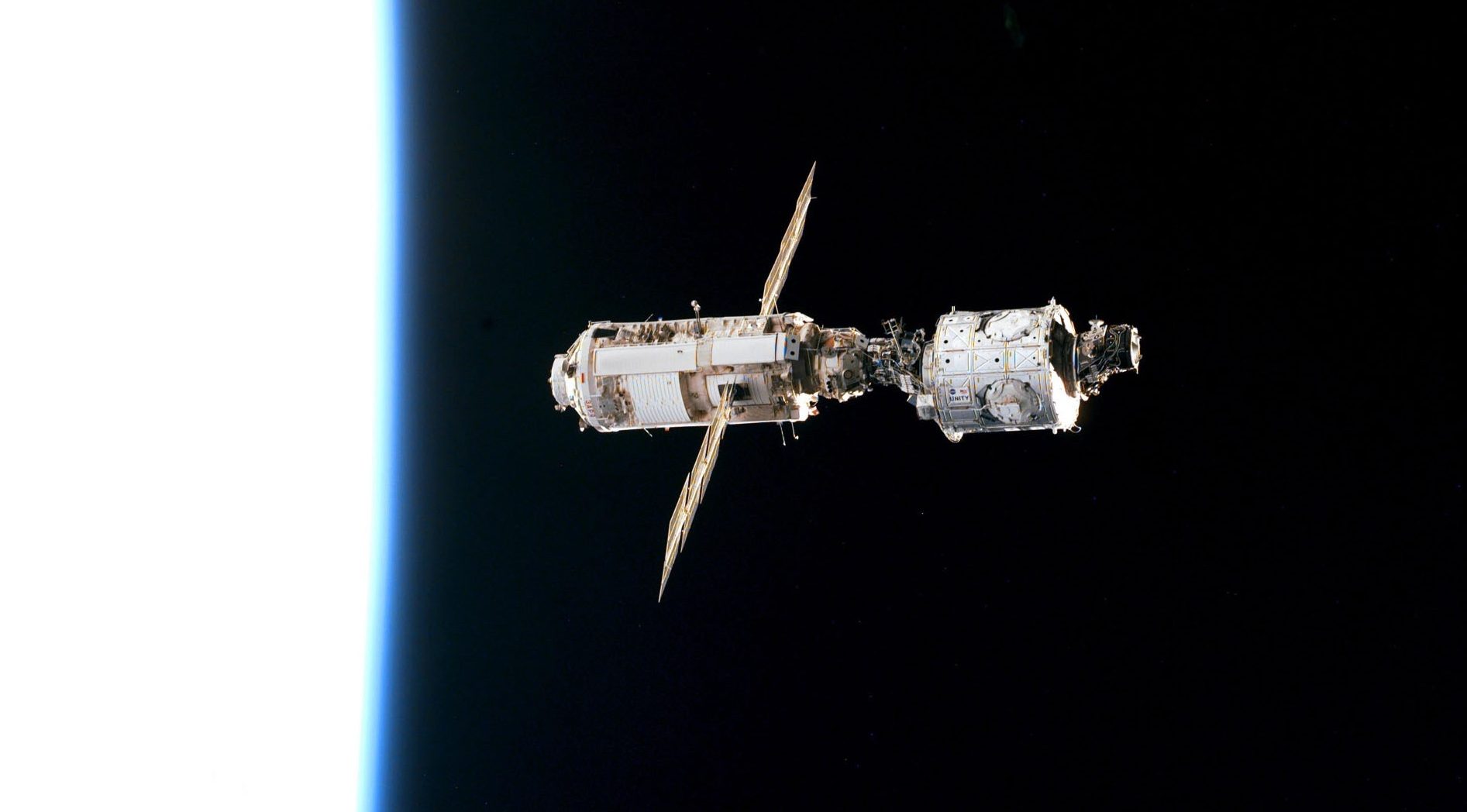

But what if certain challenges are not obstacles but roadblocks, and not technological but biological? When the problem is not what we can build, but what we are? It would be a huge blow to the future hopes of a cosmic diaspora if the obstacles were not to do with time and distance, but with the fundamental weaknesses of the human body. We’ve long known about the damaging effects spaceflight can have on the human body: bone loss, anemia, weakened immune systems, higher risks of cancer, and the list goes on. Some problems are caused by microgravity; others from the background radiation of space – NASA estimates that astronauts are exposed to the equivalent of as many as 6,000 chest X-rays. Astronauts in low Earth orbit, where the International Space Station is located, are partially protected from this radiation by Earth’s magnetosphere, but even they suffer the consequences.

Add to these effects another potentially disastrous one: space is really messing up our kidneys.

The study, ominously titled ‘Cosmic Kidney Disease’ and published last week in Nature communication, examines the kidney function of 66 astronauts who spent up to 180 days on the International Space Station, which is relatively safe compared to, for example, a return mission to Mars, which would last a few years and expose astronauts to the more intense radiation of deep space. But even that limited time had a major impact on astronauts. The study showed a significant decline in kidney function and a higher risk of kidney stones, resulting from shrinking of the renal tubules. You don’t have to be a doctor to know this is bad. And the damage could be permanent after long enough: The study simulated the effects of longer exposure on mice, and their kidneys never recovered.

Even more ominous for a long-term mission, the effects don’t begin to show until it’s too late to prevent them. “If we don’t develop new ways to protect the kidneys, I would say that even though an astronaut could get to Mars, he might need dialysis on the way back,” says Dr. Keith Siew, lead author of the study. “We know that it is too late for the kidneys to show signs of radiation damage; by the time this becomes apparent, it will likely be too late to prevent failure, which would be catastrophic for the mission’s chances of success.”

NASA is well aware of the need to provide protection against radiation, especially higher energy galactic cosmic rays, during any manned interplanetary mission, and is investigating possible solutions. One way to protect against cosmic rays is through sheer protective mass: a bulkier spacecraft. However, this chungus craft would be prohibitively heavy and expensive to launch. Another option is to use materials that shield more efficiently without weighing more. Those materials do not currently exist. Other ideas, such as force fields or drugs that counteract the effects of radiation, remain in the distant domain of theory. Currently, there is no way to go to Mars or beyond without exposing astronauts to potentially fatal doses of radiation.

It would be almost poetic if the limitations that ultimately keep us tethered to the earth were not those of distance and time, but of our bodies themselves. But it does make sense. We have evolved to live over billions of years here, and only here: so much gravity, so much radiation exposure, this temperature and pressure and atmospheric composition. When we talk about the Goldilocks zone of habitability, there is nothing special about these parameters; they are precisely the parameters for which humans are designed.

This isn’t necessarily a death sentence for space exploration and colonization; the same sci-fi brain that can imagine settling on other planets can, I don’t know, easily come up with genetic engineering to protect our kidneys from the ravages of space. But there are many very smart people who believe that these and other problems are truly insurmountable, that we will never live on other worlds. They could be right! My first reaction is that I find that disheartening, but maybe it doesn’t have to be that way. Perhaps it could actually be stimulating to know that we as a species have to live and die here. There’s no shame in that – it’s true of every other species so far – and it might be a motivation to make the best of what we have, to preserve it, to stop wasting it. If there is no escape from an uninhabitable Earth, the only choice is to repair it.