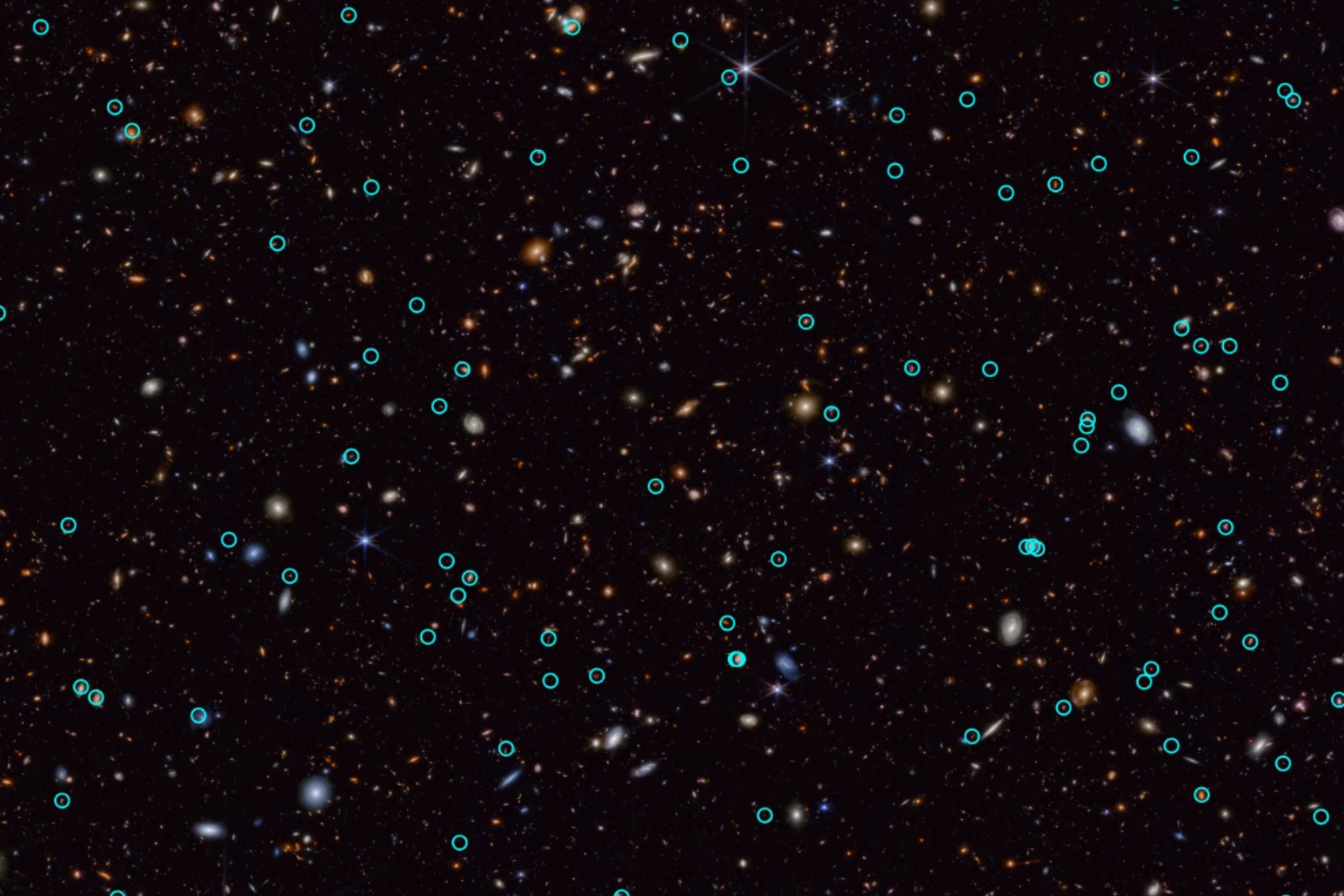

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has uncovered an unprecedented collection of ancient supernovae.

Astronomers announced that they have found ten times more of these stellar explosions than previously known in the early days of the universe. Some of these approximately 80 newly discovered supernovae exploded when the universe was only about 2 billion years old (the universe is now about 13.8 billion years old), making them among the oldest ever found.

“Webb is a supernova discovery machine,” Christa DeCoursey, a third-year student at the Steward Observatory and the University of Arizona in Tucson, said in a NASA statement. “The sheer number of detections plus the large distances to these supernovae are the two most exciting outcomes of our research.”

Supernovas are huge explosions that occur when a star dies. They emit enormous amounts of energy when the star’s core collapses as fuel runs out. These supernovae often leave behind black holes or neutron stars if the original star is large, or white dwarfs for smaller stars.

Astronomers from the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) have found these new supernovae in a tiny patch of sky, the size of a grain of rice held at arm’s length.

“Because Webb is so sensitive, he finds supernovas and other transients almost everywhere he points,” JADES team member Eiichi Egami, a research professor at the University of Arizona in Tucson, said in the statement. “This is the first important step toward more comprehensive studies of supernovae with Webb.”

The astronomers discovered these ancient supernovas thanks to a phenomenon known as cosmological redshift, in which the light from distant galaxies appears redder than it should be. This is because the universe is expanding, causing the space between galaxies to increase. Light stretches so that it shifts toward the red end of the spectrum – because red light has a longer wavelength than blue light – meaning that when astronomers observe light from distant galaxies, they see this redshift, which tells them that those galaxies that is moving away from us as a result of the expansion of the universe.

“This is really our first example of what the high-redshift universe looks like for transient science,” Justin Pierel, a NASA Einstein Fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, said in the statement. ‘We are trying to determine whether distant supernovae are fundamentally different from or very similar to what we see in the nearby universe.’

Collaboration NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI and JADES

The JWST discovery of these 80 new supernovae was unveiled by astronomers from the JADES program during a press conference at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin. Before the JWST was launched, only a few supernovae had been discovered that had a redshift value consistent with their existence when the universe was younger than about 3.3 billion years old.

One of the newly discovered supernovae exploded when the universe was only 1.8 billion years old, making it the most distant and therefore oldest supernova ever found.

The astronomers are particularly interested in types of supernovae known as Type Ia supernovae, which have predictable intense brightness. This means they can be used to calculate the expansion rate of the universe using redshift. In this recent finding, they discovered at least one Type Ia supernova from when the universe was 2.3 billion years old, making it the oldest known Type Ia supernova. This could help scientists investigate whether the brightness of these supernovas changes with redshift, which would affect their ability to be reliable predictors of the universe’s expansion rate.

These findings could also help astronomers study how supernovae in the early universe were different from those of today and how this might have affected the formation of early stars and planets.

“We are essentially opening a new window on the ephemeral universe,” STScI Fellow Matthew Siebert, head of the spectroscopic analysis of the JADES supernovae, said in the statement. “Historically, whenever we’ve done that, we’ve found extremely exciting things — things we didn’t expect.”

Do you have a tip about a scientific story that Newsweek should cover? Do you have a question about supernovas? Let us know at science@newsweek.com.

Unusual knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.