Researchers have uncovered the details of how sound behaves at different times and places Mars – and the results are very different from what we are used to on Earth.

NASAs Perseverance robber on Mars has different microphones. These devices, intended to study the properties of materials on the Red Planet, have picked up all kinds of additional sounds, including the eerie sputtering of Mars dust devils.

Recordings have already shown that sound behaves strangely on Mars. For example, sounds below 240 hertz (about middle C of a piano) travel about 10 meters per second (30 feet per second) slower than higher-pitched sounds. This is because carbon dioxide molecules, which absorb some of the energy of sound at low frequencies, make up 95% of Mars’ atmosphere. Such bizarre features, if not taken into account, could compromise communications on future Mars missions, especially crewed missions.

With this in mind, a team of scientists from French and American institutions set out to study the speed of sound and its attenuation (its tendency to decrease over distance) within the first 20 meters of Mars’ atmosphere.

To start, the team collected values of several parameters – including atmospheric pressure, temperature and chemical composition – at different locations on the Red Planet from the Martian climate database. Changes in these parameters can stretch or shrink sound waves, making these factors essential in predicting the properties of sound.

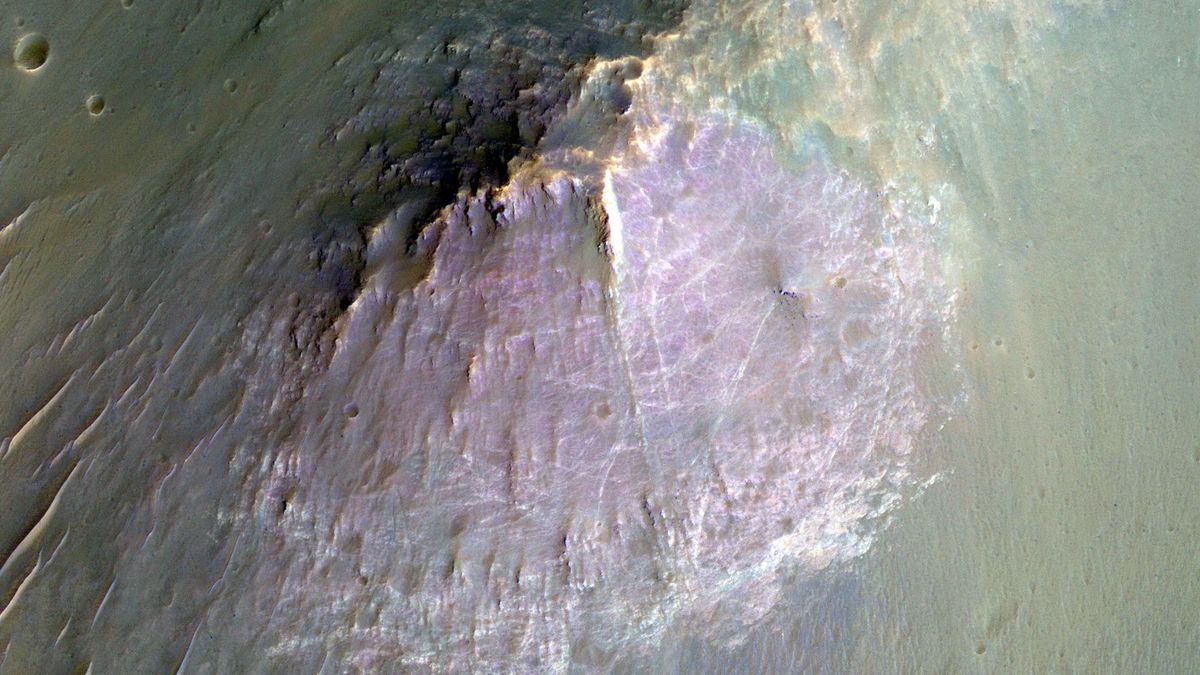

Related: Fly through the ‘Labyrinth of Night’ – a Martian canyon the size of Italy – in thrilling new satellite video

The team calculated the speed and attenuation of sound at different times in the planet’s year (that’s about 687 Earth days) and at different places in the Martian landscape, including mountain peaks and valleys. This approach was necessary because the underlying factors vary enormously in space and time. In the Arctic, for example, afternoon temperatures can fluctuate by 108 degrees Fahrenheit (60 degrees Celsius) and carbon dioxide levels by 30% throughout the seasons.

The calculations yielded several interesting findings, which were published on May 7 in the American magazine The Guardian JGR: Planets. First, dust doesn’t appear to affect the propagation of sound, the authors said in a joint email to LiveScience — similar to on Earth, where a dust storm between you and an airport, for example, wouldn’t hinder your hearing. the planes taking off. The change in the speed of sound with temperature (about 0.5 m/s for each degree Celsius) is also similar to that on Earth.

Unlike on Earth, however, the speed and attenuation of sound are strongly dependent on the carbon dioxide content. Furthermore, although the speed of sound increases abruptly around 240 hertz, the magnitude of the shift is less pronounced at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures.

The biggest difference from Earth, however, comes from the enormous fluctuations in temperature – and, to a lesser extent, the concentration of carbon dioxide – on a daily basis. For example, in the area where the Perseverance rover currently resides, mercury levels change by about 90 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius) during the day. This ensures that the sound travels at a speed of up to 30 meters per second (30 m/s) and decays three times faster in the warmer hours than in the colder hours. Changes in temperature and carbon dioxide levels also cause variations in the speed of sound and attenuation between seasons, although this effect is more pronounced in the polar regions.

The results allow scientists to “predict the speed of sound and attenuation for any location on the surface of Mars, at any time of year and at any time of day,” the researchers told LiveScience. The model could also improve scientists’ understanding of what sound-producing objects on Mars actually sound like.

‘We only hear it [a sound] after the sound has propagated through the atmosphere,” the authors said. ‘Our model can help recover the characteristics of the original sound sources.’

Moreover, the model offers a glimpse into the life of future human inhabitants on Mars: mornings on mountaintops may be the closest thing to the way sound behaves on Earth. At other times and places, such as midday at the Perseverance site, a jarring effect will occur because high-pitched sounds at close range reach the ears more quickly than lower-pitched sounds; more distant sounds normally audible on Earth will not be heard at all.