The Milky Way is only as massive as it is due to collisions and mergers with other galaxies. This is a messy process and we see the same thing happening with other galaxies in the universe.

Currently, we see the Milky Way nibbling away at its two satellite galaxies, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. Their fate is likely sealed and they will be absorbed into our Galaxy.

Researchers believed that the last major merger occurred in the Milky Way’s distant past, between 8 and 11 billion years ago. But new research reinforces the idea that it was much more recent: less than 3 billion years ago.

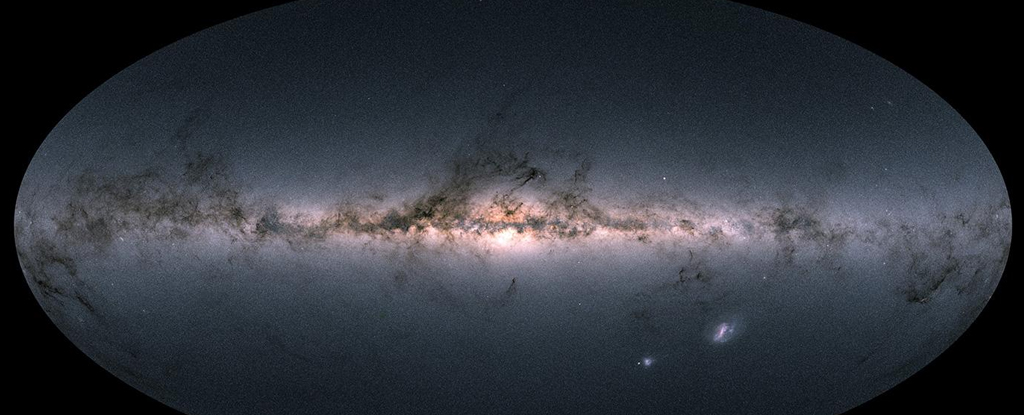

This new insight into our galactic history comes from ESA’s Gaia mission. Launched in 2013, Gaia is busy mapping 1 billion astronomical objects, mostly stars. It measures them repeatedly and provides accurate measurements of their positions and movements.

A new article published in the Monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society presents the findings. It is titled “The Debris of the ‘Last Great Merger’ Is Dynamically Young.” The lead author is Thomas Donlon, a postdoctoral researcher in physics and astronomy at the University of Alabama, Huntsville. Donlon has been studying mergers in the Milky Way for several years and has published other work on the subject.

Every time another galaxy collides and merges with the Milky Way, it leaves ripples behind. ‘Wrinkles’ is of course not a scientific term. It is an umbrella term for several types of morphologies, including phase space folds, caustics, chevrons, and shells.

These ripples move through different groups of stars in the Milky Way, affecting the way the stars move through space. By measuring the positions and velocities of these stars with great precision, Gaia can detect the ripples, the imprint of the last great merger.

“We become more wrinkled as we age, but our work shows that the opposite is true for the Milky Way. It’s a kind of cosmic Benjamin Button, becoming less wrinkled over time,” lead author Donlon said in a press release.

“By watching these ripples disappear over time, we can pinpoint when the Milky Way experienced its last major crash – and it turns out this happened billions of years later than we thought.”

The effort to understand the Milky Way’s (MW) last great merger involves several pieces of evidence. One of the pieces of evidence, along with ripples, is an Fe/H-rich region where stars follow a highly eccentric orbit.

A star’s Fe/H ratio is a chemical fingerprint, and when astronomers find a group of stars with the same fingerprint and similar orbits, it is evidence of a common origin. This group of stars is also called ‘the Splash’. The stars in the Splash may have originated from an Fe/H-rich precursor. They have strange jobs that stand out from their environment. Astronomers think they were heated and their orbits changed as a byproduct of the merger.

There are two competing explanations for all the merger evidence.

One says that a progenitor dwarf galaxy called Gaia Sausage/Enceladus (GSE) collided with the MW protodisk between 8 and 11 billion years ago. The other explanation is that an event called the Virgo Radial Merger (VRM) is responsible for the stars in the inner halo. That collision took place much more recently, less than 3 billion years ago.

“These two scenarios make different predictions about the observable structure in local phase space, because the morphology of debris depends on how long it has had to phase mix,” the authors explain in their paper.

The MW ripples were first identified in Gaia data in 2018 and presented in this paper.

“We observed shapes with different morphologies, such as a spiral that resembles a snail shell. The existence of these substructures has been observed for the first time thanks to the unprecedented precision of data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite. ESA),” Teresa Antoja, the study’s first author, said in 2018.

But Gaia has released more data since 2018, supporting the more recent merger scenario, the Virgo Radial Merger. These data show that the wrinkles are much more common than the previous data and the studies based on them suggest.

“For star ripples to be as bright as they appear in Gaia data, they would have to have joined us less than 3 billion years ago – at least 5 billion years later than previously thought,” says co-author Heidi Jo Newberg. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

If the wrinkles were much older and matched the GSE merger scenario, they would be harder to distinguish.

‘Every time the stars swing back and forth through the center of the Milky Way, new stellar ripples form. If they had joined us 8 billion years ago, there would have been so many ripples next to each other that we would no longer see them. them as separate features,” Newberg said.

This does not mean there is no evidence for the older GSE merger. Some of the stars referencing the old merger may have come from the more recent VRM merger, and some may still be associated with the GSE merger.

It’s a challenge to find out, and simulations play a big role. The researchers in previous work and in this work ran multiple simulations to see how they matched the evidence.

“Our goal is to determine the time elapsed since the precursor of the local phase-space folds collided with the MW disk,” the authors write in their paper.

“Using these simulated mergers, we can see how the shapes and number of wrinkles change over time. This allows us to determine the exact time when the simulation best matches what we see today in real Gaia data from the Milky Way – a method we used here. also a new study,” said Thomas.

“By doing this, we found that the ripples were likely caused by a dwarf galaxy that collided with the Milky Way about 2.7 billion years ago. We called this event the Virgo Radial Merger.” Those results and the name come from an earlier study from 2019.

As Gaia provides more data with each release, astronomers will gain a better view of the evidence of mergers. It becomes clear that the MW has a complex history.

The VRM likely involved more than one entity. It could have brought a whole group of dwarf galaxies and star clusters into the MW around the same time. As astronomers investigate the MW’s merger history in more detail, they hope to determine which of these objects come from the more recent VRM and which from the old GSE.

“The history of the Milky Way is currently being continually rewritten, thanks in no small part to new data from Gaia,” Thomas adds. “Our view of the Milky Way’s past has changed dramatically from a decade ago, and I think our understanding of these mergers will continue to change rapidly.”

“This finding improves our knowledge of the many complex events that shaped the Milky Way, and helps us better understand how galaxies form and form – in particular our own galaxy,” said Timo Prusti, project scientist for Gaia at ESA.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.