Microsoft Recall sounded like a really cool idea, but it quickly turned out to be a security disaster. Instead of helping you As it turns out, remembering everything you did on your Windows PC could easily help a hacker do the same.

As much as the company bungled the implementation, I do think there’s mileage in the concept, and if there’s one company I’d trust to do it with the right privacy protections, it’s Apple…

The problem that Microsoft Recall wanted to solve

We’ve probably all had the frustrating experience of reading or seeing something that didn’t seem important at the time, but would be very relevant to something we’re doing now. The frustration comes from trying to track down that information.

We dig into our browser history, or try to repeat the Google search that generated the information in the first place, but it proves a difficult and time-consuming task.

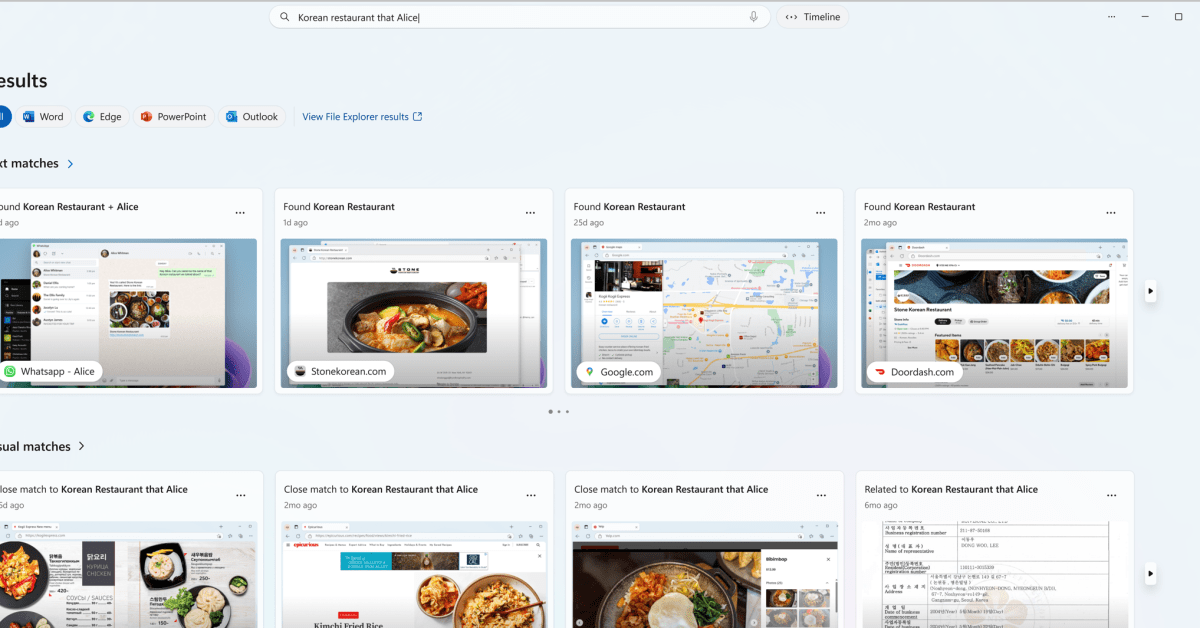

That’s the problem Microsoft Recall wanted to solve. It takes screenshots every five seconds and then uses optical character recognition to create a text database of everything that appears on our screen. We can then query that database to easily recall the contents.

For example, maybe your boss has just asked you to write a brief summary of a new technological development, and you vaguely remember seeing a statistic a few days or weeks ago that says 45% of companies are interested in it – but that could be. I can’t remember exactly where or when. With Recall you can simply search for the name of the technology and “45%” and you will immediately see the relevant document.

The security nightmare

As useful as this could be, the security risks of having a complete database of everything that was on your laptop screen should have been very clear to Microsoft, and the security measures in place were ultra-robust.

Instead, it turned out that Microsoft had given virtually no thought to how to protect the information from a hacker who had successfully compromised a PC to gain access. Kevin Beaumont was among the cybersecurity experts who showed how vulnerable the data is.

Microsoft told the media that a hacker cannot remotely exfiltrate the Copilot+ Recall activity. Reality: How do you think hackers will exfiltrate this plain text database with everything the user has ever viewed on their PC? Very easy, I automated it.

It’s just a SQLite database, the feature will ship in a few weeks – I’ve already modified it into an Infostealer hosted on Microsoft’s Github (a few lines of code) […]

I tested this with messaging apps like WhatsApp, Signal and Teams. Did someone send you a message with disappearing messages? They are admitted anyway. Write a disappearing message? It’s recorded. Delete a message? It’s recorded.

Microsoft has also managed to create an AI tool without the intelligence part. Recall has performed absolutely no checks on the nature of the information it took a screenshot of. Visible passwords? Added. Private browsing sessions? Captured. Writing in a personal Journal app? Stored. A letter entitled ‘Private and Confidential’? Scanned.

The company belatedly said it was making changes in response to some of these criticisms. Recall is now opt-in. Windows Hello (the company’s equivalent of Face ID) is required to use it. The encryption has been improved. But there still doesn’t seem to be an intelligent filter on what’s being captured, and it’ll be hard to trust a company that messed up so badly in the first place.

But I would trust Apple to do this

However, if there’s one company on the planet that I would trust to implement these types of features in a privacy-protecting way, it’s Apple.

To me, there are some pretty obvious ways an Apple version of Recall could be made more secure.

First, actual intelligence, according to the examples I mentioned above. Another simple example is excluding locked notes in the Notes app.

Second: user options. An obvious example of this is app-based lockouts, where Apple again uses intelligence to proactively suggest these, such as password managers and diary apps. Maybe we’ll turn this around and make it an app-based opt-in, so we specifically specify which apps we want to include. Or maybe the first time we open an app, we’re asked whether we should include or exclude it.

Thirdly, a scheduling function, which allows it to be turned on automatically during working hours and turned off automatically outside of work hours.

Fourth, a simple start/stop button in the menu bar. When we know we’re going to do something sensitive, we just switch the switch and the save stops. Again, some may choose to keep it disabled by default and enable it when desired.

These are all top-of-mind issues, and it’s quite astonishing to me that Microsoft didn’t think of them during the brainstorming phase of this project.

Would you like Apple to offer this?

What are your thoughts? Do you want this kind of functionality on Apple devices? Would you trust Apple to implement this in a privacy-protective way? And what additional guarantees do you want?

Take our survey and share your thoughts in the comments.

Image: Microsoft

FTC: We use monetized auto-affiliate links. More.