The rising political heat is complicating interest rate decisions in the US and Britain, where central banks are wondering whether to cut borrowing costs as voters prepare to go to the polls.

The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve want to avoid any perception that they are cutting rates to help sitting governments, former officials and economists said, making it more likely they will deviate from moves too close to Election Day.

According to former monetary policymakers, the situation is particularly difficult for the BoE as its next meeting takes place just two weeks before the July 4 general election. Governor Andrew Bailey has indicated that a rate cut is imminent.

“The central banks don’t want to appear to be playing politics at all, so the easiest thing to do is to do nothing,” said Charles Goodhart, a former member of the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee. “[But] if you don’t [move rates] this month, you can do it next month.

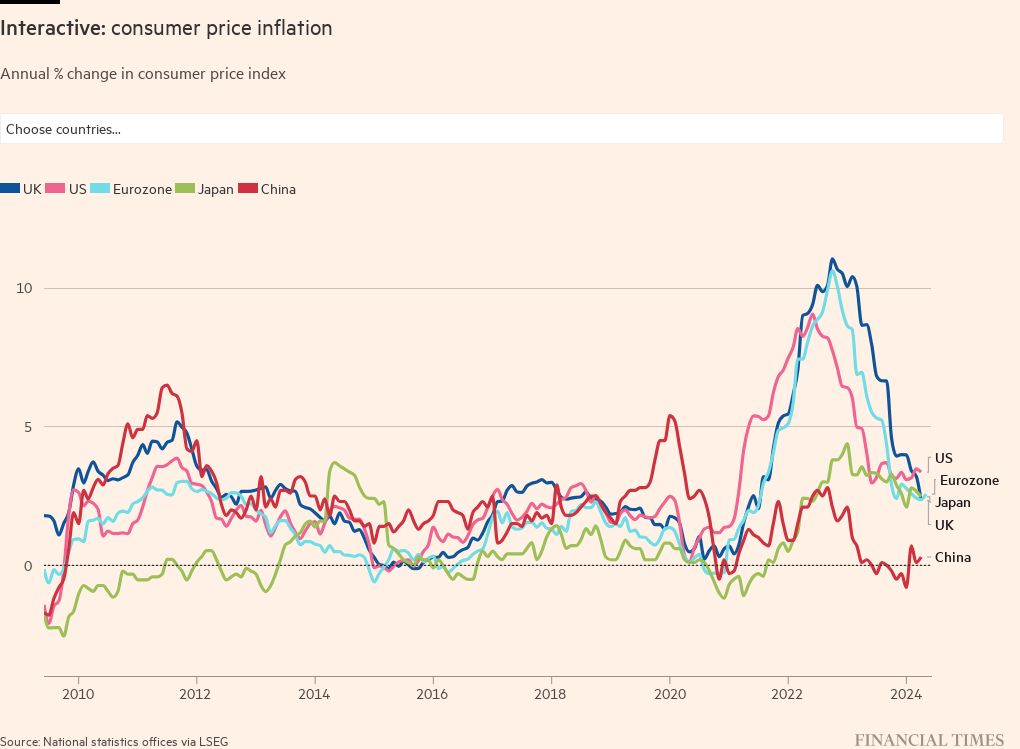

After raising interest rates to their highest level in several years in response to the worst inflation surge in a generation, Western central banks are now under intense pressure to reverse course. The Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank are among those that have already taken their first step toward looser monetary policy, implementing their first cuts last week.

But the Fed and BoE are lagging behind in weighing the effects of persistent services inflation.

In the US, the Fed faces a much longer election campaign than the accelerated process in Britain. Markets still expect the Fed to cut rates in mid-September, the last meeting before the Nov. 5 presidential election, despite a strong jobs report on Friday.

But some think this could be difficult for U.S. policymakers.

Adam Posen, director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former member of the MPC, said the strong US economy meant the Fed was unlikely to put itself in the spotlight by cutting rates before the election.

“The Fed cannot put itself on hold indefinitely, nor should it indicate that it will remain so,” he said. But he added that rate cuts were unlikely until September and “if the data allows, they will try very hard not to do anything until November”.

Although President Joe Biden has faced political pressure from some Democrats, he and his Treasury Secretary, former Fed Chair Janet Yellen, are adamant that they do not want to jeopardize the independence of the US central bank.

The data could buy the Fed time. At 2.7 percent, personal consumption expenditure inflation remains well above the 2 percent target. The labor market is cooling down more slowly than expected.

Eswar Prasad, a professor at Cornell University, said the May jobs numbers almost certainly rule out a July shutdown.

“Any Fed action, which seemed unlikely in the summer, could now come uncomfortably close to the November elections,” Prasad said. “The combination of strong employment and wage growth, coupled with persistent inflationary pressures, underlines the continued growth momentum.”

The Fed has already postponed its November meeting to take place after the election. This gap also occurred in 2020.

Others, however, argue that the Fed is unlikely to let the timing of the general election play a role. Former Fed Vice Chairman Donald Kohn said Chairman Jay Powell “has been very clear that their decisions are driven not by politics but by economics. I am confident that he will stick to it.”

He added: “So if we get to September and the labor market has weakened and inflation has remained low, I don’t see why they wouldn’t cut rates.”

In Britain, Sushil Wadhwani, another ex-MPC member, said there was no reason in principle why the BoE could not act before the election. Just a day before the June 2001 general election, he voted in favor of a rate cut, although the majority chose to leave rates unchanged.

But he added: ‘The current business environment is much more difficult for the bank because they [politicians] have said more [about rates].”

Bailey said last month that MPC members “never talk about politics” during their meetings. “Our job is to make decisions that are consistent with our mission.”

But Prime Minister Rishi Sunak suggested last month that a vote for his Conservatives rather than the opposition Labor party would be a vote for cheaper borrowing costs, in an intervention that appeared to breach the BoE’s independence.

“This most recent administration has been much more willing to express positions on monetary policy than past governments; it doesn’t seem to really understand the concept of operational independence,” said Martin Weale, member of the MPC from 2010 to 2016.

“If I were a member of the MPC, I would think I would need a particularly good reason to make a change shortly before the general election.”

UK inflation figures for April were stronger than expected, while CPI growth in the services sector fell only marginally to 5.9 percent – well above the 5.5 percent forecast by the BoE.

But if the May inflation figures, due to be published on June 19, show a clear fall in consumer prices, the case for an immediate 5.25 percent rate cut at the next BoE meeting could trump all political considerations.

“If the data on the 19th [is] sufficiently convincing. I don’t think anyone can argue with it,” Wadhwani said.