LONDON: It was a kind of accidental discovery, Volker Vahrenkamp admits with a smile.

“Sometimes these things need a little luck.”

Vahrenkamp, a professor of geology at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coast, had set out with a team of colleagues to investigate a coastal geological phenomenon they had captured on satellite images. noted, to be examined further.

The so-called teepee structures, a tent-shaped kink of sedimentary deposits found in intertidal zones, are valuable indicators of environmental change, both ancient and modern.

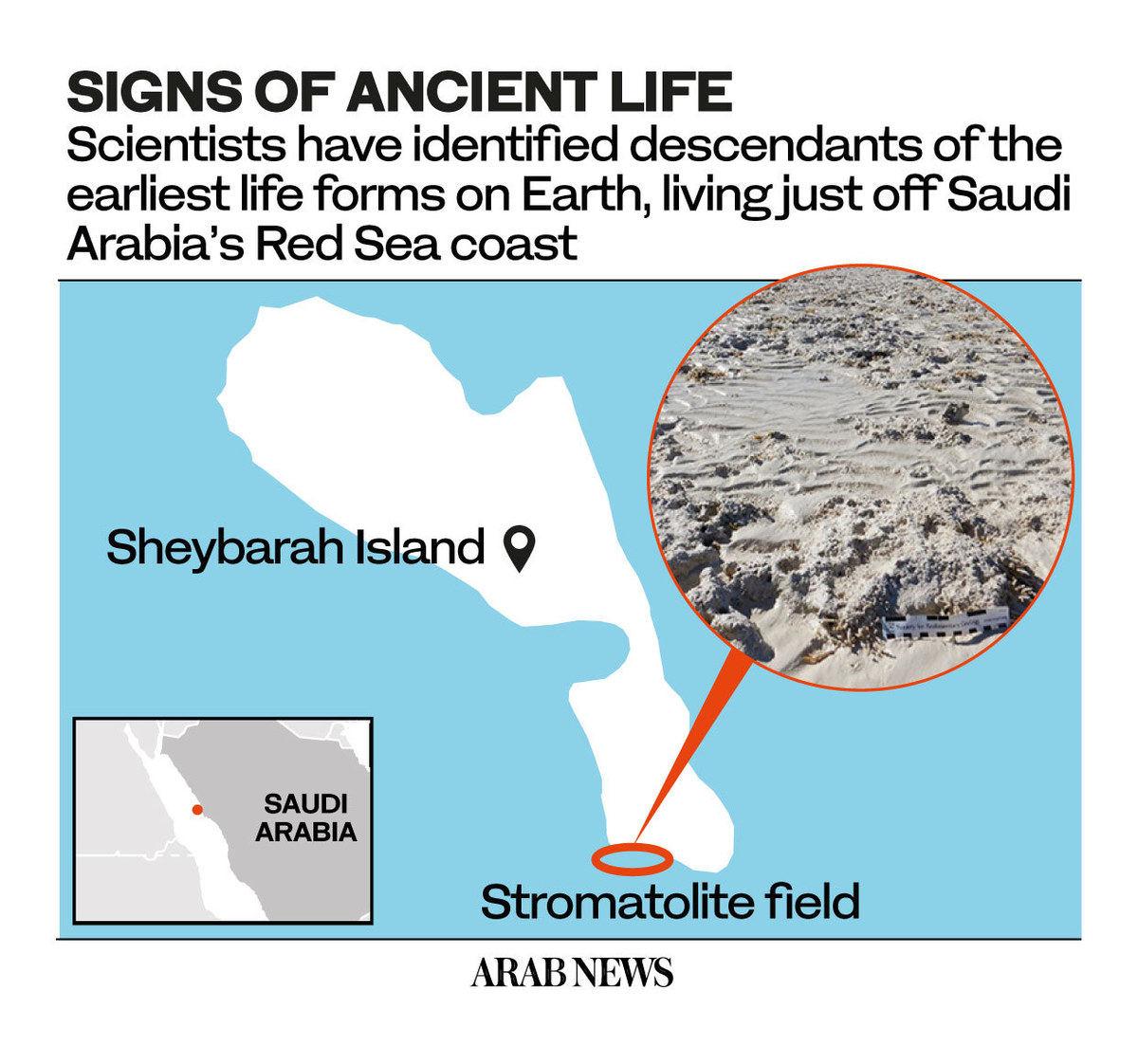

The team was delighted to discover that examples were virtually on their doorstep – just 400 kilometers up the coast of KAUST, off the southern tip of Sheybarah Island, best known for Red Sea Global’s luxury tourist resort of the same name.

“There aren’t really many good examples of teepee structures where people can study how they are formed,” Vahrenkamp told Arab News.

“Then we saw this, and it’s the most spectacular example I know of.”

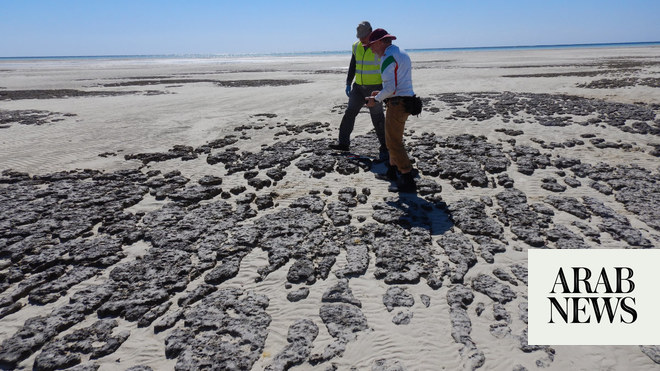

The satellite images had shown that there were two tepee fields in the intertidal zone of the island and after a short boat trip across the mainland on a converted fishing boat “we landed on the island, explored one field and then walked to the other side of the island. the other.”

And as they crossed the waterfront between the two, “we literally stepped on these stromatolites.”

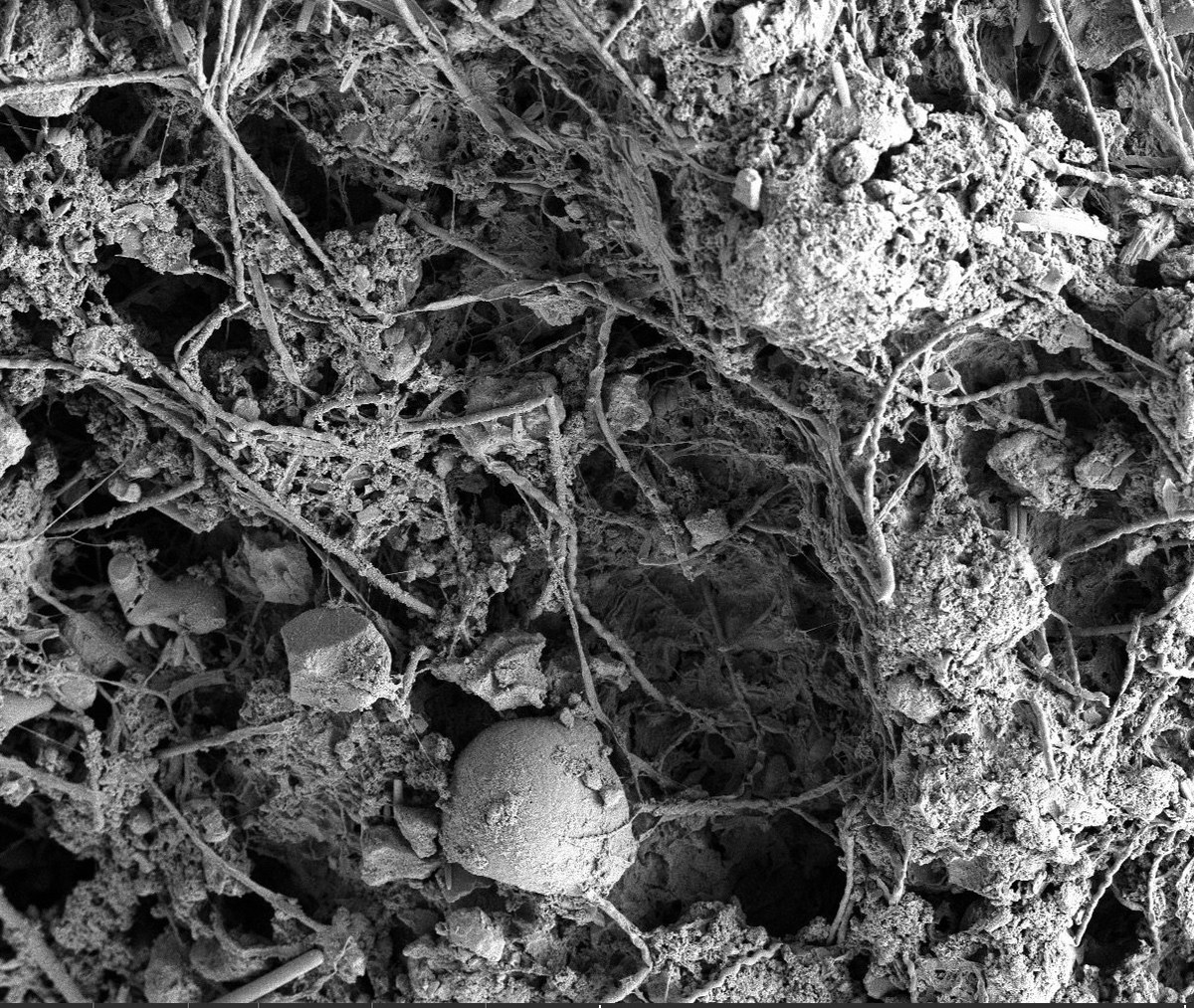

Stromatolites are layered rocky structures created by tiny microbes, individually invisible to the naked eye, some of which trap sediment in their filaments.

They live on rocks in the intertidal zone and are covered and exposed daily by the coming and going of the tides. In a process known as biomineralization, they slowly transform the dissolved minerals and sand grains they capture into a solid mass.

Humans, and every other living thing on Earth that depends on oxygen for survival, owe their existence to the tiny, so-called cyanobacteria that have been creating stromatolites for about 3.5 billion years.

Cyanobacteria were one of the first life forms on Earth, at a time when the planet’s atmosphere consisted mainly of carbon dioxide and methane. When they emerged about 3.5 billion years ago, they possessed a special ability: the ability to generate energy from sunlight.

This process, photosynthesis, had a crucial byproduct: oxygen. Scientists now believe that the microscopic cyanobacteria were responsible for the greatest thing ever to happen on Earth: the Great Oxidation Event, which transformed Earth’s atmosphere and set the stage for the evolution of oxygen-dependent life as we know it today.

Most stromatolites today are just fossils. As other life evolved on Earth, they lost their foothold in the planet’s oceans to competitors, such as coral reefs.

In a few places around the world, however, “modern” living stromatolites, “analogues for their ancient counterparts,” as Vahrenkamp puts it, continue to grow.

“Stromatolites are a remnant of the earliest life on Earth,” he said. “They ruled the Earth for an incredible period of time, about 3 billion years.

“Today they are part of the rock record in many parts of the world, but from these ancient rocks it is impossible to tell which type of microbes were involved and exactly how they did what they did.”

INNUMBERS

• 400 kilometers Distance from teepee fields to KAUST campus

• 3 billion Years when rocky stromatolites ruled the earth

• 120 Meters by which the sea level was lower during the last ice age

That’s why the discovery of a rare colony of living stromatolites, like the one-time Sheybarah Island, is such a gift to geologists, biologists and environmental scientists.

“If you find a modern example like this, chances are you can better understand how the interaction of this microbial community led to the formation of stromatolites.”

Other examples are known, but they are almost always found in extreme environments, such as alkaline lakes and ultra-saline lagoons, where competitors cannot thrive.

One previous colony was found in a more normal marine environment, in the Bahamas – which Vahrenkamp visited and is why he so easily recognized what he was walking on at Sheybarah Island – but this is the first example of living stromatolites discovered in Saudi Arabia. waters.

It is not yet clear how old these stromatolites are, “but we can estimate it somewhat,” says Vahrenkamp.

“We know that during the last ice age the sea level here was 120 meters lower, so they were not there 20,000 years ago. The area where they are located was flooded about 8,000 years ago to a height of about 2 meters above where it is today, and then the sea level dropped back to where it is now about 2,000 years ago.”

This does not mean that the stromatolites are 2000 years old. No one knows how long it takes for the microbes to make their sedimentary layer cake and “no one has yet figured out a good way to date the layers.

“The tide and waves come in and throw in sand and material from the surrounding reefs, so all kinds of ages can be present. This makes it very difficult to precisely date the stromatolites and estimate their growth rate.”

That’s why Vahrenkamp and colleagues are now devising an experiment to mimic the natural environment of rising and falling tides and alternating sunlight and darkness in an aquarium, in an effort to grow stromatolites under controlled, easily observable conditions.

Whether this will take weeks or many years, “we honestly don’t know.”

The team is also working to genetically sequence many of the thousands of different types of microbial bacteria at work in the stromatolite plant.

“It’s about finding out ‘who’ is there and who is doing what,” Vahrenkamp said

This section contains relevant reference points, posted in (Opinion field)

“But then the question also arises what kind of functionalities these bacteria have, and whether we can use them in other ways, for example in medical applications.

“Scientists are now looking closely at the microbial composition of our intestines, to find out which microbes, for example, cause cancer and which prevent it. The microbacteria at work in stromatolites may contain functional secrets that we are simply not yet aware of.”

The discovery also resonates with the environmental ambitions of the Saudi Green Initiative, announced by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2021 and which, together with the Middle East Green Initiative, aims to combat climate change through regional cooperation.

As Vahrenkamp and his seven co-authors wrote in an article recently published in Geology, the journal of the Geological Society of America, “the discovery of the Sheybarah stromatolite fields holds important implications not only in a scientific perspective, but also in terms of ecosystem services and awareness of ecological heritage, in line with the ongoing projects for sustainability and ecotourism development promoted by Saudi Arabia.”

In the article, KAUST scientists thank Red Sea Global for its support in gaining access to the stromatolite site, which is currently under consideration for designation as a protected area.

As for the tourists relaxing in the spectacular new overwater villas on Sheybarah Island’s crystal clear Al-Wajh Lagoon, an added attraction now is that a short walk along the beach will take them back in time for a glimpse of the life on Earth 3.5 billion years ago. past.