Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

German wages rose at the fastest pace in almost a decade, signaling a recovery in the broader euro zone and raising doubts about how aggressively the European Central Bank will cut interest rates this year.

Collectively agreed wages in Germany rose 6.2 percent in the first three months of the year, compared with 3.6 percent in the previous quarter, according to Bundesbank figures that include one-off bonuses published on Wednesday.

Economists said the German figures, together with data from other countries, suggested that annual collective wage growth in the euro zone rose to 4.7 percent in the first quarter, up from 4.5 percent in the previous quarter. The overall figures for the currency bloc will be published on Thursday.

An acceleration in wages would be a setback for investors hoping for successive rate cuts from the ECB, which is widely expected to be the first major central bank to cut rates on June 6.

The euro zone’s central bank has said the timing of the interest rate cuts will depend on whether workers get lower pay increases this year and whether those extra costs are absorbed by companies that cut profit margins rather than pass them on with higher prices.

Stronger-than-expected wage growth in the first quarter will mean policymakers are unlikely to agree on a second consecutive cut in July and are more likely to wait until September. The interest-sensitive yield on two-year German government bonds rose above 3 percent for the first time in three weeks on Wednesday, after investors lowered their expectations for a rate cut.

“This will pose a significant challenge to the idea that the ECB will implement successive rate cuts,” said Tomasz Wieladek, economist at investor T Rowe Price. “It is likely that the ECB will cut rates further in June as this was actually announced in advance and it will be difficult to deviate from this forward guidance at this stage.”

ECB policymakers have been sending strong signals for several months that they are likely to start cutting deposit rates from a record high of 4 percent in June, as long as inflation does not rise higher than they expected.

Christine Lagarde, president of the ECB, said this week that there is a “high probability” that the central bank will cut borrowing costs at its June meeting “if the data we receive reinforces the level of confidence we have that we will cut 2 percent deliver”. inflation in the medium term”.

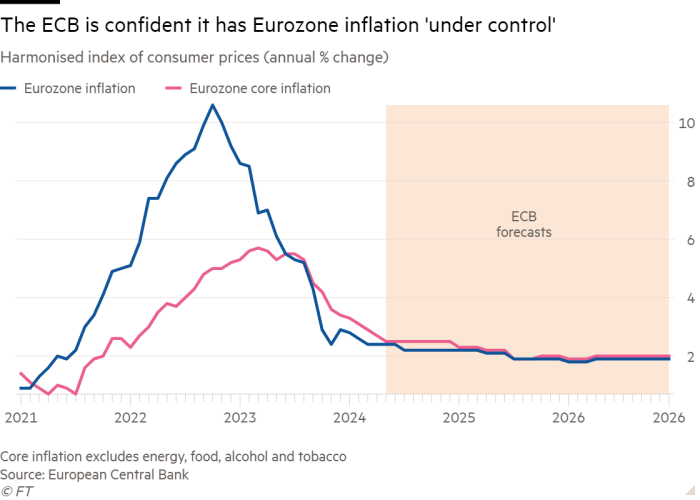

Eurozone inflation remained stable at 2.4 percent in April, after falling from above 10 percent at its peak in 2022, and Lagarde said it was “under control”.

But other ECB policymakers have warned investors not to expect consecutive rate cuts in June and July. “Even if rates are cut for the first time in June, that does not mean we will cut rates further,” Bundesbank chief Joachim Nagel said this week. “We don’t work on autopilot.”

Germany’s central bank said: “The widespread labor shortages and high willingness to strike, which have recently allowed unions to achieve above-average enforcement rates, also suggest that wage increases will remain relatively high in the future.”

According to the report, recent collective wage agreements, which increased annual wages by an average of 11.7 percent in March, indicated that wage growth in Europe’s largest economy was likely to remain high, especially in the services sector. The unions aim for annual wage increases of between 7 and 15 percent.

Greg Fuzesi, an economist at US bank JPMorgan, said the latest payroll data “could remind some policymakers of the difficulty of the last mile.” [in bringing inflation down to target] with recent disappointments in productivity also playing a role in this.”

But he added that the broader trend of easing wage pressures remained largely unchanged as the institutionalized nature of Germany’s wage negotiations meant increases were “slow in coming through” and wage growth in other countries slowed.