New research shows that the Sun’s magnetic field originates near the surface and not deep within the star. . This upends decades of prevailing scientific thinking, which placed the field more than 130,000 miles below the surface of the sun. It also brings us closer to understanding the nature of the Sun’s magnetic field, which scientists have been thinking about since Galileo.

The study, and a team of international researchers, suggests that the magnetic field actually generates 20,000 miles (32,000 kilometers) below the surface. This was discovered after the team performed a series of complex calculations on a NASA supercomputer. It’s worth noting that these are just initial findings and more research is needed to confirm the data.

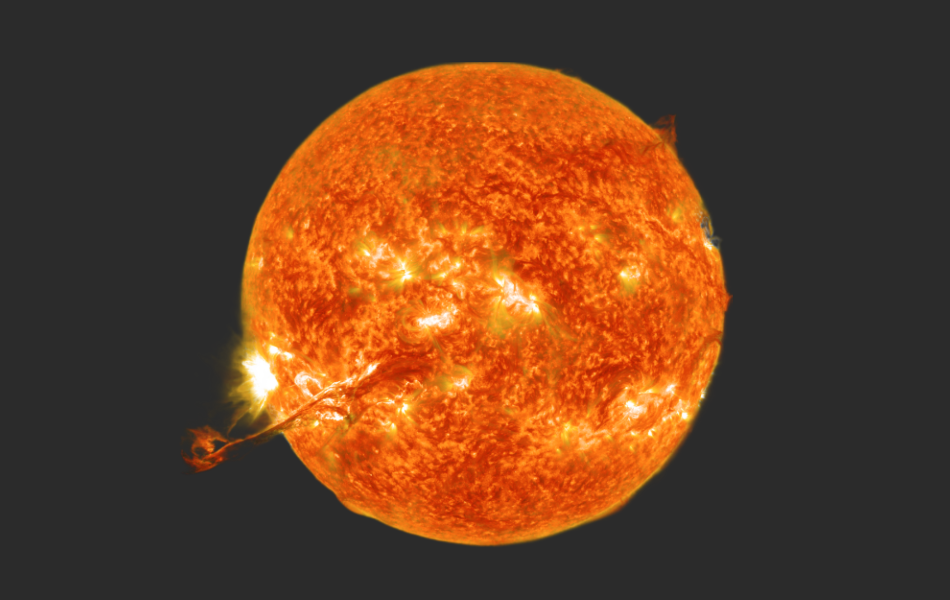

The sun’s magnetic field fluctuates in a cycle that lasts eleven years. During the strongest part of this cycle, powerful winds and sunspots form at the solar equator, along with plumes of material that create it here on Earth. Previous theories that place the magnetic field deeper in the Sun have struggled to connect these different solar phenomena. Scientists hope that, with further research, they can use this theory to not only explain the origins of solar events, but also to more accurately predict when they will occur.

Every second, 1.5 million tons of solar material, traveling at a speed of 160 kilometers per second, shoots away from the sun. Earth’s magnetic field deflects most of it, but not all of it. The solar wind, a stream of charged particles, flows at a speed of 447 km/s (1 million mph), and while the magnetic field protects… pic.twitter.com/40CSNZYesU

— Historical Videos (@historyinmemes) January 1, 2024

This could lead to more than just previous predictions of the next Aurora Borealis event. The sun’s intense magnetic energy is also the source of solar flares and bursts of plasma called coronal mass ejections. When these emissions travel towards Earth, all kinds of bad things happen. This famously happened in 1859, when a gigantic geomagnetic storm created the largest solar storm in history.

This is attributed to the British astronomer Richard Christopher Carrington. The solar flare, which was actually a magnetic explosion on the Sun’s surface, briefly surpassed the Sun and caused colored light to erupt over the entire planet, similar to the aurora borealis. It also boosted telegraph wires, shocked operators and set telegraph paper on fire. It was pretty nasty.

This was 1859, before the modern use of electricity and before computers and all related technologies. If something like the Carrington event were to happen today, . The emitted X-rays and ultraviolet light would disrupt electronics, radio and satellite signals. The event would cause a solar radiation storm, which would be fatal for astronauts not fully equipped with protective equipment.

It would also cause a coronal mass ejection to collide with Earth’s magnetic field, like cell phone satellites, modern cars and even airplanes. The resulting global power outages could last for months. Last month’s small (relatively speaking) storm was not a Carrington-sized event. Even worse? This is absolutely meant to happen. It’s basically a ticking time bomb.

So these findings could theoretically be used to prepare new early warning methods for large-scale solar flares hitting Earth. One day we might get solar flare warnings in addition to hurricane warnings and the like. The research has already shown some interesting connections between sunspots and the sun’s magnetic activity.

“We still don’t understand the sun well enough to make accurate predictions” of solar weather, lead study author Geoffrey Vasil of the University of Edinburgh . These new findings “will be an important step toward finally solving” this mysterious Northwestern University process.

This article contains affiliate links; if you click on such a link and make a purchase, we may earn a commission.