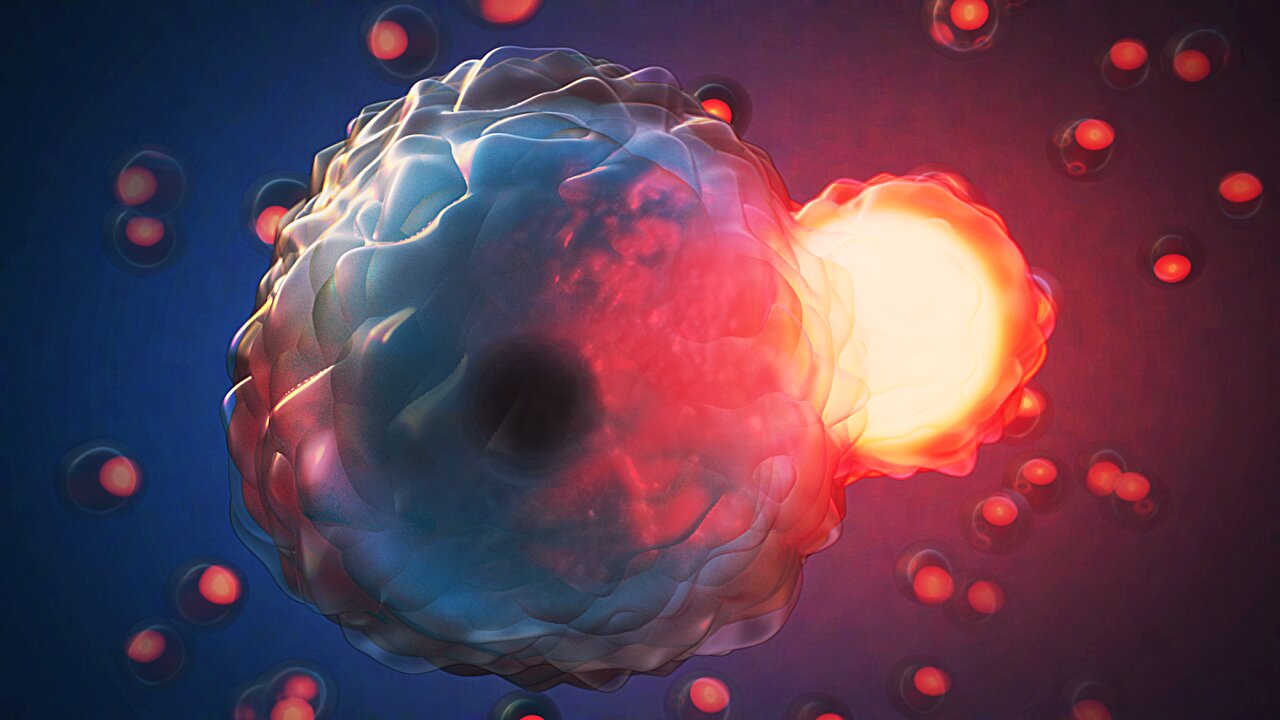

In addition to competing for resources, living cells actively kill and eat each other. New explorations of these ‘cell-within-cell’ phenomena show that they are not limited to cancer cells, but are a common facet of living organisms throughout the tree of life. Credit: Jason Drees, Arizona State University

× close to

In addition to competing for resources, living cells actively kill and eat each other. New explorations of these ‘cell-within-cell’ phenomena show that they are not limited to cancer cells, but are a common facet of living organisms throughout the tree of life. Credit: Jason Drees, Arizona State University

In a new review article, Carlo Maley and colleagues from Arizona State University describe cell-within-cell phenomena in which one cell engulfs and sometimes eats another. The research shows that cases of this behavior, including cell cannibalism, are widespread throughout the tree of life.

The findings challenge the common perception that cell-in-cell events are largely confined to cancer cells. Rather, these events appear to be common in diverse organisms, from single-celled amoebae to complex multicellular animals.

The widespread occurrence of such interactions in non-cancerous cells suggests that these events are not inherently ‘selfish’ or ‘cancerous’ behaviour. Rather, the researchers argue that cell-in-cell phenomena may play a crucial role in normal development, homeostasis and stress response in a wide range of organisms.

The study argues that targeting cell-in-cell events as an approach to treating cancer should be abandoned because these phenomena are not unique to malignancy.

By showing that events span a wide range of life forms and are deeply rooted in our genetic makeup, the research invites us to reconsider fundamental concepts of cellular cooperation, competition and the complicated nature of multicellularity. The study opens new avenues for research in evolutionary biology, oncology and regenerative medicine.

The research, published in Scientific reports, is the first to systematically investigate cell-in-cell phenomena in the tree of life. The group’s findings could help redefine the understanding of cellular behavior and its implications for multicellularity, cancer and the evolutionary journey of life itself.

“We first started this work because we learned that cells not only compete for resources, but actively kill and eat each other,” says Maley. “That’s a fascinating aspect of cancer cell ecology. But further research revealed that these phenomena occur in normal cells, and sometimes neither cell dies, resulting in an entirely new type of hybrid cell.”

Maley is a researcher at the Biodesign Center for Biocomputing, Security and Society; professor in ASU’s School of Life Sciences; and director of the Arizona Cancer Evolution Center.

The study was conducted in collaboration with first author Stefania E. Kapsetaki, formerly at ASU and now a researcher at Tufts University, and Luis Cisneros, formerly at ASU and currently a researcher at Mayo Clinic.

From selfish to cooperative cell interactions

Cell-within-cell events have long been observed but remain poorly understood, especially outside the context of immune responses or cancer. The earliest genes responsible for cell-in-cell behavior date from more than 2 billion years ago, suggesting that the phenomena play an important, but yet undetermined, role in living organisms. Understanding the diverse functions of cell-in-cell events, both in normal physiology and disease, is important for developing more effective cancer therapies.

Phylogenetic tree of multicellularity and cell-in-cell phenomena. Credit: Scientific reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-57528-7

× close to

Phylogenetic tree of multicellularity and cell-in-cell phenomena. Credit: Scientific reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-57528-7

The review delves into the occurrence, genetic underpinnings and evolutionary history of cell-in-cell phenomena, shedding light on behavior once considered an anomaly. The researchers reviewed more than 500 papers to catalog the different forms of cell-within-cell phenomena observed in the tree of life.

The study describes 16 different taxonomic groups in which cell-in-cell behavior occurs. The cell-in-cell events were classified into six different categories based on the degree of relatedness between the host and prey cells, as well as the outcome of the interaction (whether one or both cells survived).

The study highlights a spectrum of cell-within-cell behavior, ranging from completely selfish actions, in which one cell kills and eats the other, to more cooperative interactions, in which both cells remain alive. For example, the researchers found evidence of “heterospecific killing,” in which one cell engulfs and kills a cell from another species, in a wide range of unicellular, facultative multicellular and obligate multicellular organisms. In contrast, ‘similar killing’, where one cell consumes another cell of the same species, was less common and was observed in only three of the seven major taxonomic groups examined.

Obligate multicellular organisms are organisms that must exist in a multicellular form throughout their entire life cycle. They cannot survive or function as individual cells. Examples of this are most animals and plants. Facultative multicellular organisms are organisms that can exist as single cells or in a multicellular form depending on environmental conditions. For example, certain types of algae can live as single cells under certain conditions, but form multicellular colonies under others.

The team also documented cases of cell-in-cell phenomena in which both host and prey cells remained alive after the interaction, suggesting that these events may serve important biological functions beyond just killing competitors.

“Our categorization of cell-in-cell phenomena in the tree of life is important for better understanding the evolution and mechanism of these phenomena,” says Kapsetaki. “Why and how exactly do they happen? This is a question that requires further research in millions of living organisms, including organisms where cell-in-cell phenomena may not yet have been explored.”

Old genes

In addition to cataloging the diverse cell-in-cell behaviors, the researchers also examined the evolutionary origins of the genes involved in these processes. Surprisingly, they found that many of the most important cell-in-cell genes arose long before the evolution of obligate multicellularity.

‘When we look at genes associated with known cell-in-cell mechanisms in species that diverged from the human lineage very long ago, it appears that the human orthologs (genes that evolved from a common ancestral gene) are generally associated with normal functions of multicellularity, such as immune surveillance,” says Cisneros.

A total of 38 genes associated with cell-in-cell phenomena were identified, and 14 of them arose more than 2.2 billion years ago, older than the common ancestor of some facultatively multicellular organisms. This suggests that the molecular machinery for cell cannibalism evolved before the major transitions to complex multicellularity.

The ancient cell-in-cell genes identified in the study are involved in a variety of cellular processes, including cell-cell adhesion, phagocytosis (engulfment), intracellular killing of pathogens and regulation of energy metabolism. This diversity of functions indicates that cell-within-cell events likely played an important role even in unicellular and simple multicellular organisms, long before the emergence of complex multicellular life.

More information:

Stefania E. Kapsetaki et al., Cell-within-cell phenomena in the tree of life, Scientific reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-57528-7

Magazine information:

Scientific reports