Adani Group has dismissed low-quality coal as a much more expensive cleaner fuel in deals with an Indian state-owned energy company, according to evidence from the Financial Times that sheds new light on allegations of a long-running coal scam.

The documents, secured by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and reviewed by the FT, add a potential environmental dimension to the corruption allegations linked to the Indian conglomerate. They suggest that Adani may have fraudulently made huge profits at the expense of air quality, because using low-grade coal for energy means burning more fuel.

Invoices show that Adani purchased an Indonesian batch of coal in January 2014 that reportedly contained 3,500 calories per kilogram. The same consignment was sold to the Tamil Nadu Generation and Distribution company (Tangedco) as 6,000-calorie coal, one of the most valuable grades. Adani appears to have more than doubled his money, after deducting transport costs.

The FT has also matched documentation for a further 22 shipments in 2014 involving the same parties, indicating a pattern of inflation in the supply of 1.5 million tonnes of coal.

Adani sourced the coal in Indonesia from a mining group known for low-calorie production, at prices consistent with low-grade fuel. It supplied the coal to India’s southernmost state for power generation and fulfilled a contract that required expensive, high-quality fuel.

According to a 2022 study in The Lancet, more than two million people in India die every year from outdoor air pollution, while other studies show that infant mortality has increased significantly in hundreds of kilometers around coal-fired power stations.

Another study from a decade ago found that coal-fired power stations, which supply about three-quarters of India’s electricity, were responsible for about 15 percent of man-made emissions of particulate matter, 30 percent of nitrogen oxide and 50 percent of man-made emissions. caused particulate matter emissions. cent sulfur dioxide.

“Public health has definitely taken a back seat in India, against the interests of the energy sector,” said Sunil Dahiya, a New Delhi-based analyst at the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

Opposition politicians last year called for an investigation into Adani after the FT reported that the group paid more than $5 billion to middlemen for coal imported into India between 2021 and 2023, far above market prices.

The latest revelations come as Adani aims to transform itself into a major player in renewable energy, including by building one of the world’s largest wind and solar farms in Khavda, near the border with Pakistan. The group, which denies wrongdoing, remains one of India’s largest coal importers.

The findings are also likely to help intensify political debate in India over the power and influence of billionaires, including Gautam Adani, whose names and vast wealth have emerged during the current election campaign as Narendra Modi seeks a third term as prime minister. .

India’s Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI), the finance ministry’s investigative unit that monitors economic crime, opened an investigation into coal prices in 2016. The prosecution of a businessman in connection with $68 million in alleged coal price inflation is one of the few tangible outcomes of that ongoing investigation.

New documents obtained by the OCCRP and shared with the FT show how in December 2013 the MV Kalliopi L ship left Indonesia carrying coal with a list price of $28 per tonne. When it arrived in India in the new year, Adani sold the coal to Tangedco for $92 per tonne.

The coal came from the operations of Indonesian mining group PT Jhonlin in South Kalimantan, where the ship was loaded.

An export declaration from PT Jhonlin stated that Tangedco was the end buyer and gave Adani’s details as the intermediary. However, Jhonlin’s invoice went to British Virgin Islands-based Supreme Union Investors, which was charged $28 per tonne.

A week later, Supreme Union Investors invoiced Adani in Singapore for the shipment at $34 per tonne, stating that the coal contained 3,500 calories per kg.

On Adani’s subsequent invoice to Tangedco, the quality rose to 6,000 calories, as did the price, to $92 per tonne.

Other documents suggested the discrepancy was not isolated. A 2014 purchase order lists 32 deliveries of 6,000 calories of coal to Tangedco by Adani, for a total of 2.1 million tons at $91 per ton. The warrant was released under India’s freedom of information laws, following a request from OCCRP.

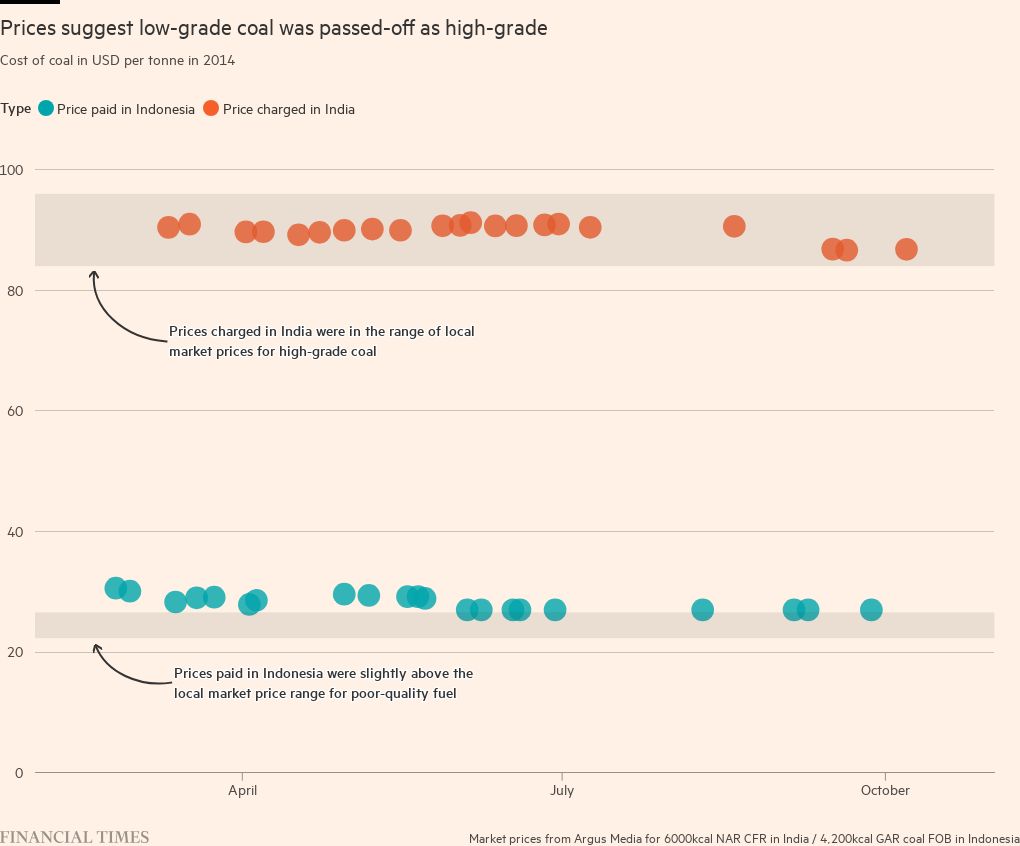

According to internal Jhonlin data, Supreme Union Investors acted as an intermediary for 24 of the cargoes listed in Tangedco’s purchase order, purchasing them at an average price of $28 per tonne. According to Argus data, freight rates were slightly above the benchmark for 4,200-calorie coal from Indonesia, which was trading between $22 and $26 per tonne at the time.

The FT matched 22 of the 24 trips with registrations from India; for all 22 shipments, Tangedco was the end buyer at an average price of $86 per tonne. The price is in line with Argus’ estimates of local market prices for high-quality 6,000-calorie coal, which were between $81 and $89, including freight costs.

Argus’s contemporary price estimates for freight costs imply that for every tonne sold for an average of $86, Adani and its intermediaries shared up to $46 in profits. This totaled approximately $70 million for the 22 voyages.

Adani denies allegations of fraud. A spokesperson for the group said the quality of the coal was tested independently at the point of loading and unloading, as well as by customs authorities and Tangedco scientists: “Because the coal supplied has passed such an extensive quality control process by multiple agencies at multiple It is clear that the claim about the supply of low-quality coal is not only baseless and unfair, but also completely absurd.”

Tangedco, Jhonlin, Supreme Union Investors and the DRI did not respond to requests for comment.

“Given the market power of coal suppliers, [utilities] often have no choice but to accept grade discrepancies,” says Rohit Chandra, assistant professor of public policy at IIT Delhi. “Third-party testing has done very little to address these concerns.”

The transactions fit a pattern of endemic fraudulent price inflation that Indian authorities alleged in 2016 in a notice that listed five Adani companies and five importers supplied by the group among 40 entities investigated.

The DRI announcement alleged that offshore intermediaries were being used to inflate the price of coal supplied to utilities, and that “in a significant number of cases” two sets of test reports for shipments were discovered: “one with a lower gross calorific value (GCV) and one with a lower calorific value (GCV) and the other higher GCV”.

Arappor Iyakkam, a non-governmental organization based in Tamil Nadu’s capital Chennai, alleged a “coal billing scam” in a complaint to the state Directorate of Vigilance and Anti-Corruption in 2018.

The NGO, which focuses on transparency issues, said Tangedco paid above market price for coal and that the calorific value of coal quoted on tenders and purchase orders did not match what was received.

“Tangedco has suffered heavy losses [billions of rupees] every year for the past ten years,” the NGO said in its complaint. “We need to understand that this directly translates into higher energy tariff for the common man and has major implications for the common man.”

The NGO estimated that a total of Rs60 billion ($720 million) was wasted on Tangedco’s coal procurement between 2012 and 2016. ($360 million),” Jayaram Venkatesan, the NGO’s chairman, told the FT.

Adani’s spokesperson said the NGO had “repeated DRI’s allegations”. India is the world’s second largest consumer and producer of coal after China. But strong demand and rail bottlenecks mean the country must also import, with Indonesia being the largest supplier of thermal coal.

In a 2017 report, India’s Comptroller and Auditor General raised questions about whether Tangedco’s tender process for imported coal favored major groups like Adani. The inadequate time for submitting bids and the high turnover requirement for bidders were pointed out. The DRI’s investigation is still ongoing and is delayed by legal proceedings related to international document requests.

Adani said it was vindicated by the DRI’s decision last year to withdraw its appeal to the Supreme Court in a case against one of 40 importers listed in 2016.

Industry analysts say testing of the calorific value of coal – including stringent requirements for random sampling of coal racks – is rigorous and carried out by third-party agencies in India. But because it all happens with human intervention, there is room for abuse, they note. The costs of testing are usually divided between the supplier and the end user on the loading side, and are borne by the end user on the unloading side.

“A wide variation” between a shipment’s declared calorific value and its actual value “can only happen with the cooperation of the people on the unloading side,” said a senior energy industry official.

Tangedco documents include multiple certifications by its own scientists and third-party testing companies that the coal supplied by Adani under the 2014 purchase order met specifications.

A person who works on India’s power grid said the primary focus was on continuity of coal supply and balancing generation to meet demand, meaning any issue of coal quality was a “post hoc exercise” .

An Adani spokesperson said: “That is not possible by any stretch of the imagination [Adani’s Singapore subsidiary]with a total supply of less than 2 percent of the coal that Tangedco burned during the relevant period, be held responsible for air pollution or the losses” of India’s state-owned power distribution companies.