Off the coast of Big Sur, California, deep beneath the waves, lies a mysterious landscape littered with large holes in the clay, silt and sand.

Decades after its discovery, scientists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and Stanford University believe they have discovered what makes up the field’s curious circular pattern.

The generally accepted theory is that pockmarks on the ocean floor are the product of methane gas, or even hot liquids, flowing up from the Earth’s interior and blowing away some fine sediment. But while that may be true for underwater cavities in some parts of the world, that’s not always the case.

Exceptions to the rule are piling up.

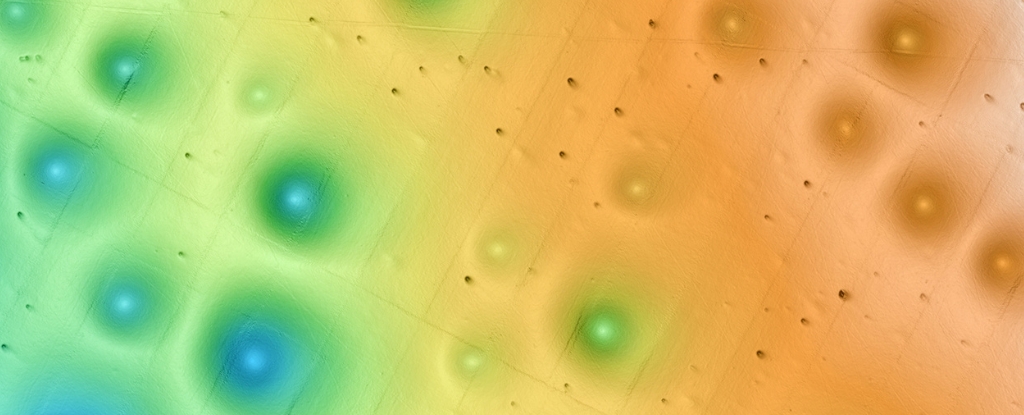

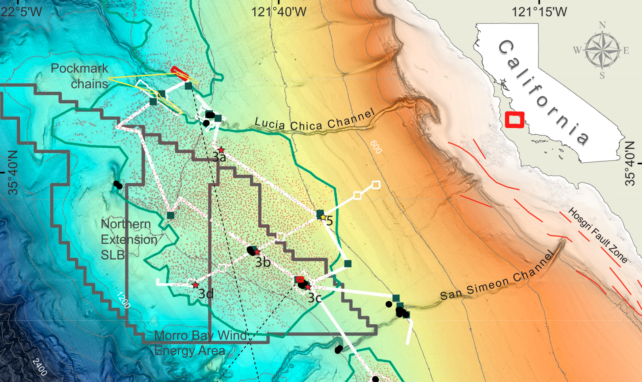

The Sur Pockmark Field off the coast of California is the largest of its kind in North America. It is about the size of Los Angeles and contains more than 5,200 cavities, the average of which extends up to 175 meters wide and 5 meters deep.

The site is planned for a potential offshore wind farm, but there are concerns that the presence of methane could undermine the stability of the infrastructure.

During a recent expedition to the Sur-pockmarks, which are located at depths of 500 to 1,500 meters, an underwater robot piloted by MBARI researchers found “little evidence” of methane vents or other fluid flows. Instead, the team thinks that smallpox was probably created by sheer gravity.

The large impressions are on a continental slope, and seafloor samples collected by the robot suggest that sediment has flowed intermittently down this slope over the past 280,000 years. The last major flow occurred 14,000 years ago, possibly due to an earthquake or slope collapse.

Researchers at MBARI claim that such events can lead to erosion at the center of each pockmark. When a large enough amount of sediment rolls down, it can even cause “enough erosion” to carve out a wider pockmark, causing the edges of “multiple pockmarks to shift tens of kilometers apart,” the team suggests .

This may cause smallpox to appear in ‘chains’, although future modeling is needed to confirm that idea.

“We collected a tremendous amount of data, which allowed us to make a surprising connection between pockmarks and sediment gravity flows,” says MBARI research technician Eve Lundsten.

“We couldn’t determine exactly how these pockmarks initially formed, but with MBARI’s advanced underwater technology, we’ve gained new insight into how and why these features have persisted on the seafloor for hundreds of thousands of years.”

The Sur Pockmark field is said to be one of the best studied seafloors on the west coast of North America. But that doesn’t say much. Researchers still don’t know how sediment or fluid moves through the field.

Until recently, experts did not know that porpoises and eels caused the smallest holes seen in a similar pockmarked field in the North Sea.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard writing; encrypted media; gyroscope; photo within photo; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

It is sometimes said that the seabed is the Earth’s last frontier. The race is on to scan this alien world not only for scientific curiosity, but also for the viability of new industries, such as offshore wind farms or seabed mining. But it’s one thing to observe an ecosystem, and quite another to understand it.

“Expanding renewable energy is critical to achieving the dramatic reductions in carbon emissions needed to prevent further irreversible climate change,” said Chris Scholin, president and CEO of MBARI.

“However, there are still many unanswered questions about the potential environmental impacts of offshore wind energy development. This research is one of many ways MBARI researchers are answering fundamental questions about our ocean to help inform decisions about how we use marine resources to use.”

The research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research Earth Surface.