Of all the places I expected to learn fundamental lessons about therapy, playing a game about vampire therapists wasn’t one of them. Yet I did, and now I wonder why I ruled out such a possibility in the first place. Games have a unique power in their interactivity that is perfect for education (although I’ve sat through plenty of terrible corporate training videos trying to do the same thing). That Vampire Therapist can teach me concepts normally associated with more rigid education shouldn’t really come as a surprise. What is surprising is that no one has tried this approach for this topic before.

Vampire Therapist is a game about seeking and providing therapy, specifically cognitive behavioral therapy. I’ve experienced this a bit in my real life. As far as I can tell, it’s a way to change thought patterns to identify unhelpful ways of thinking. It also provides skills to help deal with problematic situations. It’s the talking part of the therapy that the game focuses on, although I’ve only played a few hours of it. And it’s developed with the help of licensed therapists, so it’s not all bullshit.

Apologies for the American slang, but I picked it up from the character in the game you’ll be playing as: Sam Walls, a cowboy from the Wild West who left behind a life of bloody gunslinging to get his head straight and face the bad things he’d done. In the name of this quest, he heads to present-day Leipzig, Germany, to meet the ancient vampire therapist Andromachos and learn more. Sam already has the makings of a therapist – he’s come to many insights of his own – but it’s Andromachos who formalizes his training and helps him become the therapist he becomes.

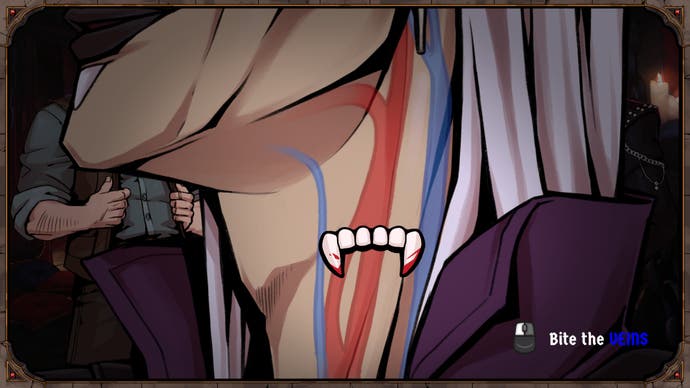

It’s a visual novel of sorts, a conversational game. The gameplay almost always revolves around two characters talking and chatting (with voice acting). The only time I’ve seen that change is when I had to bite someone’s neck – I had to press my button so that my fangs would stop right above their carotid artery, which was really fun. But mostly it’s conversations.

In those conversations, you have a few dialogue choices, but the point is to provide a place to point out cognitive distortions when you see them. Cognitive what-now? Exactly—this is where the game gets therapeutic, but it never overwhelms you. Cognitive distortions are ways of talking that aren’t helpful. Early in the game, Sam has created a few for himself. He’s given them his own names: Hot Branding, High Noon Mind, and Saloon Thinking.

Hot Branding is where people give themselves names – Sam compares it to branding yourself with a hot iron. High Noon Mind refers to someone who talks in all-or-nothing extremes, as if the situation is do or die. And Saloon Thinking is how someone might talk in a bar, either confidently or self-loathingly. Andromachos formalizes these as Nosferatu Thinking (a pun on the fact that it’s a black and white film and the statements are black and white; High Noon Mind), as Labelling (Hot Branding) and as Control Fallacy (Saloon Thinking), and he quickly adds a couple more: Disqualifying the Positive and Should Statements. These then appear as buttons beneath the conversation text, which can be pressed when you recognize someone talking that way.

As I said, you’re introduced to it gently. Sam is a character who’s good at thinking things out loud, Andromachos is a good teacher, and there’s a detailed but not dense diary with extra information if you want it. A lot of effort has been made to make the information accessible. The game moves slowly: first it’s Andromachos examining Sam, then it’s Sam examining patients, the complexity increasing the more you play. The fact that the game doesn’t take itself too seriously – it cites famous vampire properties like What We Do in the Shadows as inspiration – helps immensely to ease the anxiety. I laughed out loud a few times; it’s a game that likes a joke. It helps that Sam is likable too – he reminds me a lot of Ted Lasso, both in his accent and his boundless enthusiasm and in his constant willingness to give people a philosophical pep talk, while Andromachos is patient and calm.

What still amazes me about Vampire Therapist is how powerful an easy-going game can be in teaching real, heavy therapy concepts—though there’s a broader question of whether that’s a responsible thing to do; it can be dangerous to self-diagnose, or worse, impose your views on someone else. But the impression I get from the game in this regard is a responsible one. It seems more focused on expanding understanding of cognitive behavioral therapy than replacing it in any way. It also never loses sight of the fact that it’s a game—that it’s entertainment. That’s partly why it’s so easily absorbed. You just watch a bunch of conversations and try to identify cognitive dissonances as they surface, and if you get it wrong, it doesn’t matter: Andromachos says try again.

It’s slowly sinking in—and I mean really sinking in. I’m taking the advice and lessons I’ve learned in the game to heart. I’m paying attention to the “shoulds” in my sentences and all-or-nothing statements I make. I’m looking for ways in which I’ve unnecessarily put pressure on situations and how I can alleviate that. I’m being a little kinder to myself, and that’s nice. It’s positive. And it’s remarkable how quickly and subtly a game can have that effect.

A copy of Vampire Therapists was provided by Little Bat Games.