June 25, 2024, marked a new “first” in spaceflight history. China’s Chang’e 6 spacecraft brought back rock samples from a vast region of the moon called the South Pole-Aitken Basin. After landing on the moon’s “far side,” the southern rim of the Apollo Crater, Chang’e 6 returned with about 1.9 kg of rock and soil, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) said.

The moon’s south pole has been earmarked as the site for the future China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). This truly international undertaking has partners including Russia, Venezuela, South Africa and Egypt, and is being coordinated by a kind of ad hoc international space agency.

China has a strategic plan to build a space economy and become a world leader in this field. It plans to explore and extract minerals from asteroids and bodies such as the moon, and to use water ice and other useful space resources available in our solar system.

China wants to explore the moon first, then asteroids known as near-Earth objects (NEOs). Then it will move on to Mars, asteroids between Mars and Jupiter (known as main belt asteroids) and Jupiter’s moons, using the stable gravitational points in space known as Lagrange points for its space stations.

Scharfsinn / Shutterstock

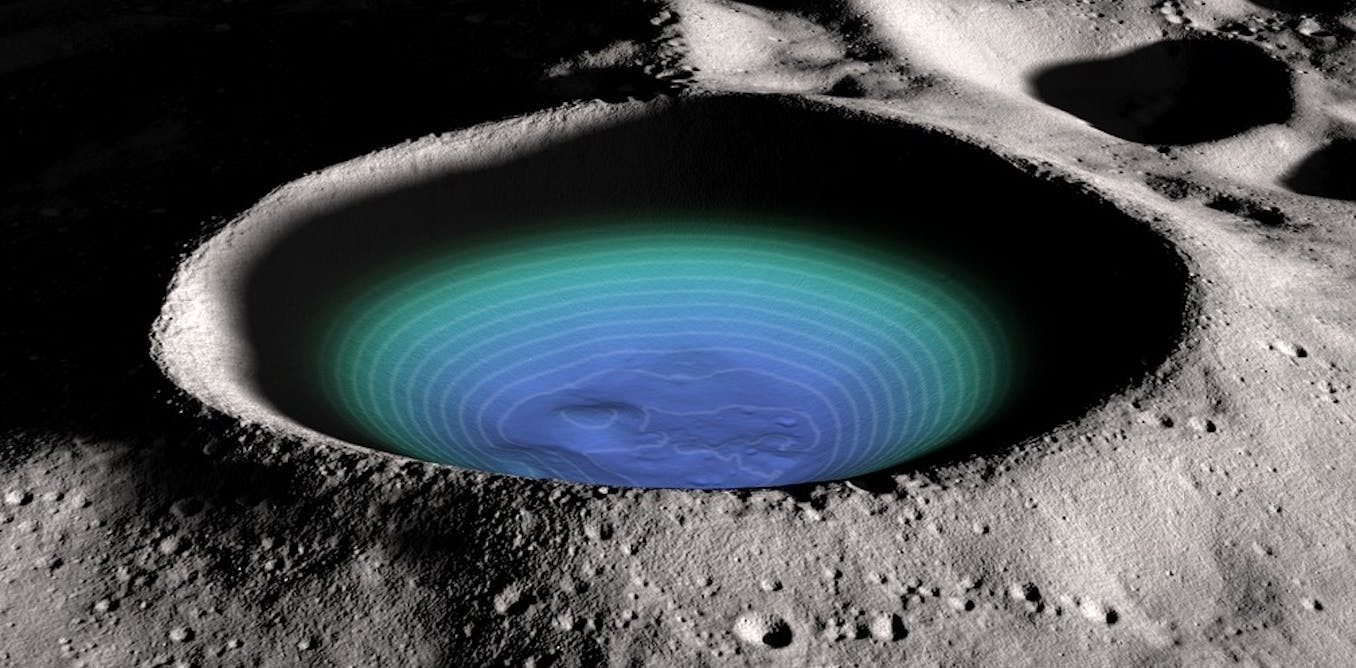

One of China’s next steps in this strategy, the robotic Chang’e 7 mission, is expected to launch in 2026. It will land on the illuminated rim of the moon’s Shackleton Crater, very close to the moon’s south pole. The rim of this large crater has a point that is constantly illuminated, in an area where the angle of the sun casts long shadows that obscure much of the landscape.

As a landing site it is particularly attractive – not only because of the illumination, but also because of the easy access it offers to the inside of the crater. These shadowed craters contain enormous reserves of water ice, which will be essential for the construction and operation of the ILRS, as the water can be used for drinking water, oxygen and rocket fuel.

It’s a bold move, given that the US also has ambitions to establish bases at the moon’s south pole – Shackleton Crater is a prime location. A later Chinese mission, Chang’e 8 (currently scheduled for no earlier than 2028), will aim to extract ice and other resources and demonstrate that it’s possible to use them to support a human outpost. Both Chang’e 7 and 8 are considered part of ILRS and will set the stage for an impressive Chinese exploration program.

NASA is currently seeking additional partners for the international agreement known as the Artemis Accords, which were drawn up in 2020. They govern how lunar resources are to be used, and so far 43 countries have signed up. However, the US Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the moon this decade, has been delayed due to technical problems.

NASA-

It’s normal to experience delays in any complex new space program. The next mission, Artemis II, which will take astronauts around the moon without landing, has been delayed until September 2025. Artemis III, which is supposed to bring the first humans to the lunar surface since the Apollo era, is not scheduled to launch until September 2026.

While the Artemis timeline could go back even further, China could make good on its plans to land humans on the moon by 2030. Some commentators are even questioning whether the Asian superpower can beat the US to the moon landing target.

Geopolitics in space

Will the US land humans on the moon by the end of the decade? I think so. Can China do it by 2030? I doubt it – but that’s not the point. China’s space program is growing systematically in a consistent and integrated way. Its missions don’t seem to have encountered the serious technical problems that other ventures have – or maybe we’re just not being told about them.

Alejo Miranda / Shutterstock

What we do know for sure is that China’s current space station, Tiangong – which translates as “Heavenly Palace” – is operational at an average altitude of 400 km. There is a plan to have it permanently inhabited by at least three taikonauts (Chinese astronauts) by the end of the decade. By the time this happens, the International Space Station, which orbits at the same altitude, will have been dismantled and sent on a fiery descent into the Pacific Ocean.

Geopolitics is returning as a force in space exploration in a way we perhaps haven’t seen since the space race of the 1950s and 1960s. It’s quite possible that the US Artemis III mission and the Chinese Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8 missions will all aim to land at the same location, close to Shackleton Crater.

Only the crater rims can serve as good landing sites, so there may be no choice but for China and the US to exchange plans and use this renewed phase of space exploration as a new era in diplomacy. While maintaining national priorities, the two superpowers, along with their partners, may need to agree on common principles when it comes to lunar exploration.

China has come a long way since its first satellite, DongFangHong 1, was launched on April 24, 1970. China was not a player during the original space race to the moon in the 1960s and 1970s. Now it certainly is.