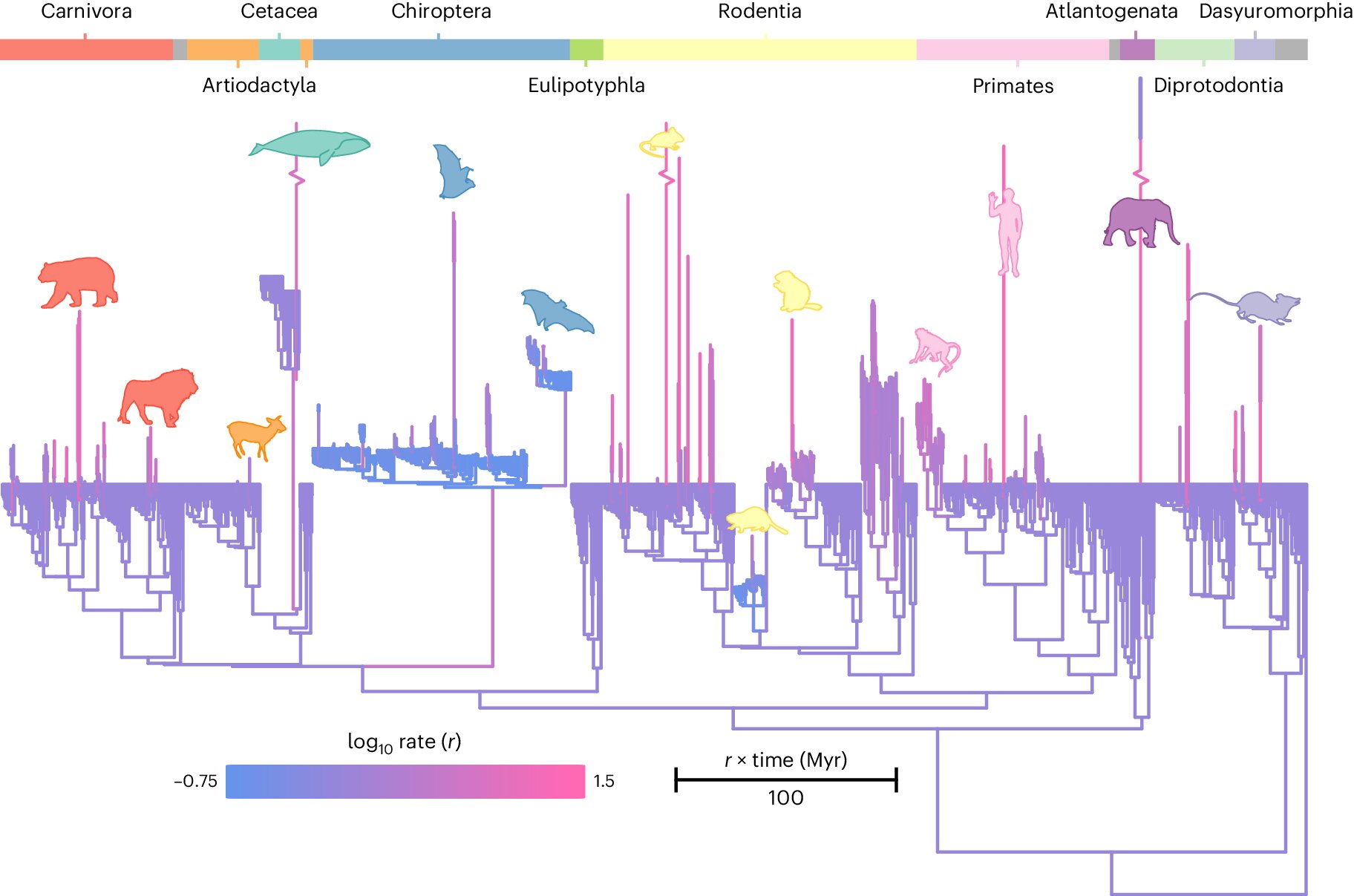

Rate of relative evolution of brain mass. Credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024). DOI file: 10.1038/s41559-024-02451-3

The largest animals don’t have proportionally larger brains, and humans are an exception to this trend, according to a study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution has revealed.

Researchers from the University of Reading and the University of Durham have compiled a huge dataset on the brain and body sizes of around 1,500 species, in an effort to clarify centuries of controversy surrounding the evolution of brain size.

Larger brains relative to body size have been linked to intelligence, sociality and behavioral complexity, with humans having evolved exceptionally large brains. The new research reveals that the largest animals do not have proportionately larger brains, challenging long-held beliefs about brain evolution.

Professor Chris Venditti, lead author of the study from the University of Reading, said: “For more than a century, scientists have assumed this relationship was linear, meaning that brain size increases proportionally as an animal gets bigger. We now know that this is not true. The relationship between brain and body size is a curve, which effectively means that very large animals have smaller brains than expected.”

Professor Rob Barton, co-author of the study from Durham University, said: “Our results help to resolve the confusing complexity in the relationship between brain and body mass. Our model has a simplicity that means previously elaborate explanations are no longer necessary: relative brain size can be studied using a single underlying model.”

Outside the ordinary

The study found that there is a simple relationship between brain size and body size across all mammals, allowing the researchers to identify the offenders: species that challenge the norm.

Among these outliers is our own species, Homo sapiens, which has evolved more than 20 times faster than any other mammal, resulting in the enormous brains that define humanity today. But humans are not the only species to buck this trend.

All mammal groups showed rapid changes, both toward smaller and larger brain sizes. Bats, for example, reduced their brain size very rapidly when they first evolved, but then showed very slow changes in relative brain size, suggesting that there may be evolutionary constraints related to the demands of flight.

There are three groups of animals that show the most pronounced rapid change in brain size: primates, rodents, and carnivores. In these three groups, there is a tendency for relative brain size to increase over time (the “Marsh-Lartet rule”). This is not a universal trend for all mammals, as was previously thought.

Dr Joanna Baker, co-author of the study, also from the University of Reading, said: “Our results reveal a mystery. In the largest animals, there is something that prevents brains from growing too big. Whether this is because large brains are simply too expensive to maintain above a certain size remains to be seen. But since we also see similar curvatures in birds, the pattern seems to be a general phenomenon: whatever causes this ‘strange ceiling’ applies to animals with very different biology.”

More information:

Chris Venditti et al, Co-evolutionary dynamics of mammalian brain and body size, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024). DOI file: 10.1038/s41559-024-02451-3

Offered by the University of Reading

Quote: Brain size riddle solved as humans exceed evolutionary trend (2024, July 8) Retrieved July 9, 2024, from https://phys.org/news/2024-07-brain-size-riddle-humans-exceed.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair dealing for private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The contents are supplied for information purposes only.