NASA’s Viking was the first American spacecraft to land on Mars, sending back images of craters, massive volcanoes and giant canyons from its surface. In the 1970s, NASA launched two identical robots — Viking 1 and Viking 2, each equipped with landers and orbiters — to the Red Planet. After the mission, NASA reported that it had found no signs of life. But one scientist is almost certain that it unwittingly stumbled upon alien life and dismissed it, Live Science reported.

“After landing on the Red Planet in 1976, NASA’s Viking landers may have collected small, drought-resistant life forms hiding in Martian rocks,” Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at the Technical University of Berlin, suggested in an article in Big Think. He said he and his fellow scientist, Joop Houtkooper, were rethinking the results of the Viking project.

“If these extreme life forms existed and persisted, the experiments the landers performed might have killed them before they were identified, because the tests would have overwhelmed these potential microbes,” Schulze-Makuch wrote, according to Live Science. He added that microbes that survive in similar conditions live on Earth and could therefore also live on Mars.

The Viking robots conducted four experiments on Mars: the Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) experiment, for organic or carbon-containing compounds in the Martian soil; the Labeled Release (LR) experiment, for testing metabolism by adding radioactively grown nutrients to the soil; the Pyrolytic Release (PR) experiment, for carbon fixation by potential photosynthetic organisms; and the Gas Exchange experiment, for monitoring gases.

The results of these experiments were vague. In both LR and PR experiments, they found small changes in the concentrations of gases, which indicated that some kind of metabolism was taking place and that there could be life on Mars. GC-MS also found traces of organochlorine compounds. However, the results were dismissed by scientists who thought that the experimental instruments were contaminated by cleaning solutions containing chlorine. And when the gas experiment gave a negative result, the idea of life on Mars was dismissed once and for all.

But Schulze-Makuch had other ideas, since most of these experiments required adding water to the Martian soil samples. He gave the example of the 2018 study on the Atacama Desert, which showed that microbes died in the presence of water. He hypothesized that the use of water in these experiments must have killed the microbes lurking in the soil samples collected on the Red Planet.

Additionally, Alberto Fairén, an astrobiologist at Cornell University and co-author of the 2018 study, told Live Science he “totally agrees” that adding water to the Viking experiments could have killed off potential hygroscopic microbes that might have hidden signs of life on Mars.

Schulze-Makuch, Houtkooper and Alberto weren’t the only ones who believed that life had been discovered on Mars. One of the principal investigators of the NASA experiment that sent Viking landers to Mars, Gilbert Levin, stated repeatedly over the years that the Viking experiment had detected life, according to CNN. Levin published an article in Scientific American magazine in which he said, “I’m convinced that we found evidence of life on Mars in the 1970s.”

“NASA has already announced that its 2020 Mars lander will not include a life-detection test,” Levin wrote. “In accordance with well-established scientific protocol, I believe an effort should be made to include life-detection experiments on the next Mars mission.” He suggested repeating the LR experiment on Mars. “(In the 1970s) NASA concluded that LR had found a substance that mimicked life, but not life… inexplicably, in the 43 years since Viking, none of NASA’s subsequent Mars landers have carried a life-detection instrument to follow up on these exciting results.”

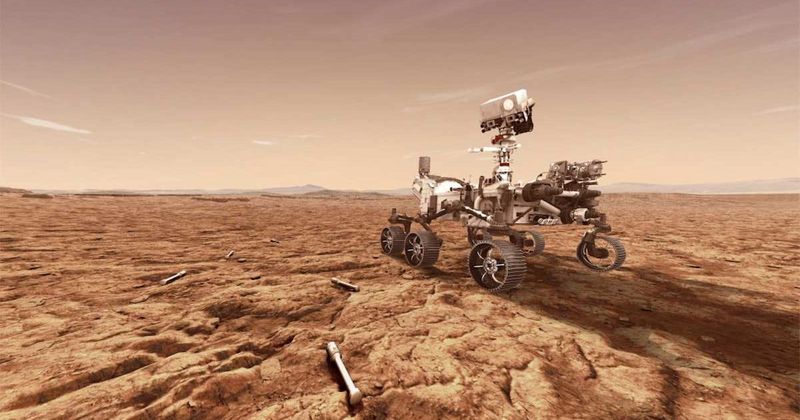

However, NASA’s later missions have yielded somewhat conflicting results. In 2007, NASA’s Phoenix lander, the successor to the Viking, found traces of perchlorate on Mars. Perchlorate is toxic to plants and microorganisms. On the other hand, NASA’s Perseverance rover from 2020 found organic material on Mars, in the form of sediments that indicated the existence of “saline lakes” somewhere on Mars. This is possible because, according to NASA, Mars was a wet planet billions of years ago and also had a lake. However, despite all these hypotheses, there is currently no solid evidence indicating the existence of life on Mars.