A bone from the Baishiya Karst cave in Tibet suggests that Denisovans lived there about 40,000 years ago, long after modern humans had spread across much of Asia. Combined with earlier evidence of their presence in the area 190,000 years ago, the find reveals an extraordinary persistence in the face of exceptionally difficult circumstances. It also raises the possibility that we won’t like the answer to what ended this remarkable run.

Extinct members of humanity are always mysterious, but the Denisovans are particularly obscure. The only known fossil records of them come from three caves, but they live on a little in our genes, or at least in the DNA of people with East Asian or Australasian ancestors.

Because so much of the picture is missing, every new fossil find is invaluable. But it also likely raises more questions than it answers. Such is the case with a rib found at Baishiya.

The bone is one of more than 2,500 preserved in the cave, dating from 190,000 to 30,000 years ago. However, almost all of them come from prey animals, not humans.

Study co-author Dr Geoff Smith from the University of Reading explained in a statement: “We were able to establish that Denisovans hunted, slaughtered and ate a range of animal species. Our study reveals new information about the behaviour and adaptation of Denisovans to both high-altitude conditions and changing climates. We are only just beginning to understand the behaviour of this extraordinary human species.”

Most of the bones Smith and coauthors studied were so badly broken that previous attempts had been unable to identify their sources. By using mass spectrometry on collagen in the bones, however, the team was able to link 2,005 of them to a species, or at least a genus, revealing much about the area’s changing ecosystem.

Among the yaks, small birds, woolly rhinos, and even blue sheep (no, not green sheep) lay a single bone from a Denisovan. It was dated to somewhere between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago—a big difference by many standards, but enough to know that its owner lived during the last Ice Age and after modern humans had spread through Asia.

Co-author Dr Jian Wang from Lanzhou University said: “The current evidence suggests that it was Denisovans, and not other human groups, who inhabited the cave and made efficient use of all the animal resources at their disposal.”

The discovery confirms that Denisovans used the cave during the last ice age and the ice age before that. Prey continued to accumulate during the interglacial period, so Denisovans were almost certainly responsible for that too, even though we have no examples of their own bones from that time.

The Denisovan rib bone, broken during excavations. So far it is not known whether the owner was given the nickname Adam.

Photo: Dongju Zhang’s group (Lanzhou University).

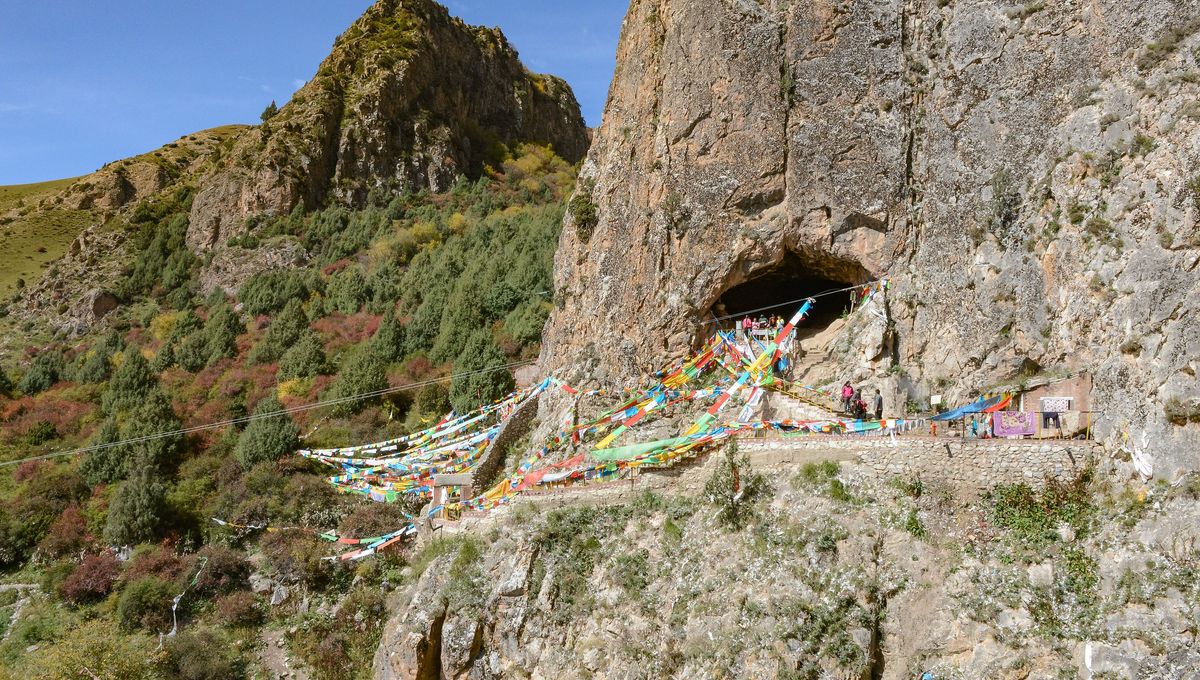

Baishiya Cave has long been a place of pilgrimage for Buddhists, but we can only speculate whether local memories of its ancient use have contributed to the cave being considered sacred.

In 2019, it was revealed that the inhabitants there 160,000 years ago were Denisovans, not Neanderthals as previously thought. This marked the first discovery of Denisovan bones outside the cave after which they are named. More precisely, it was probably the first identification of Denisovan bones elsewhere – it is likely that we have found their bones in other places and attributed them to other branches of the human family tree.

Denisova Cave is a forbidding place today. At the same latitude as London, it gets much colder in the winter, thousands of miles away from the moderating effects of the oceans. Baishiya, on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, is much further south but also 3,300 meters (10,800 feet) above sea level, making it much colder still. To survive there during an ice age, the Denisovans must have been exceptionally well adapted to the cold.

On the other hand, the fact that their genes are most prevalent in New Guinea today shows that they could also handle the heat. Perhaps their greatest legacy to modern humans is the genes that allow modern Tibetans to thrive in the oxygen-poor conditions at such altitudes.

But despite all this, the Denisovans themselves are gone, and their DNA is a small part of the modern gene pool. “The question now arises as to when and why these Denisovans became extinct on the Tibetan Plateau,” says Dr. Frido Welker of the University of Copenhagen. Given that modern humans were already well established in the surrounding areas by this point, the answer is probably not so pretty.

The study has been published open access in the journal Nature.