Blackstone Group has become one of the largest buyers of a type of bank debt that has become a lifeline for the private equity industry, exposing the company to the risks that come with running its own business.

The world’s largest buyout group, which manages more than $1 trillion in assets, has emerged over the past year as a major investor in risk-transfer products backed by short-term loans used by private equity fund managers to close deals while they wait for money from their investors.

Because of its vast size, Blackstone has taken on risk on credit lines tied to its own buyout funds, though the firm said these represent only “a single-digit percentage” of the portfolios it is exposed to.

Such transactions increase the private equity giant’s exposure if an investor is unable or unwilling to finance its investment.

“The unusual thing about Blackstone is that it’s a bit circular,” said one major SRT investor. “They’re protecting themselves.”

The deal underscores how complex and interconnected the private capital sector has become, and how new areas of risk can emerge in less regulated corners of the financial system.

Banks in Europe and the US have increasingly encountered investors willing to take on some of the default risk on their loan portfolios through so-called significant risk transfer transactions (SRTs).

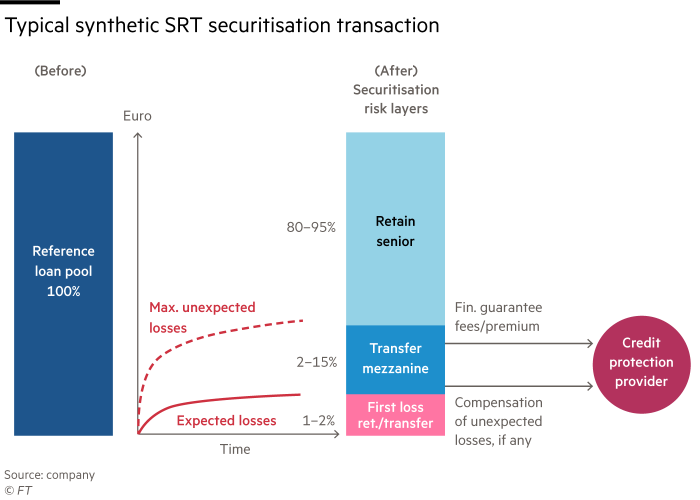

Such risk transfer agreements allow lenders to reduce the amount of capital they are required to hold by regulators and thereby increase their returns.

Blackstone recently became a major investor in subscription-backed SRTs, short-term loans used by private equity funds to close deals before they receive money from their investors.

For several years, private equity firms have been financing their corporate buyouts with debt provided by their own credit funds. The recent SRT transactions, which themselves can be partially financed with bank debt, come at a time when regulators are increasingly concerned about the lack of transparency in private markets.

Blackstone President Jonathan Gray told investors in an April earnings call that the group was a “market leader” in SRTs. He highlighted subscription lines as an area of particular interest because they are seen as safe assets.

“The most active area so far has been the subscription lines, which … have had virtually no defaults for the last 30, 40 years. So we like that area,” he said.

Blackstone disputed the circular nature of the risk, saying its investors are “the ultimate risk counterparty to which the lender is exposed.” It noted that its investors had never missed a capital call in its 40-year history.

The group added that its funds made up “a single-digit percentage of the portfolios for which we provided SRTs” and that all of its subscription line SRTs “were in highly diversified portfolios”.

According to insiders, the Wall Street-listed group bought the assets through its investment unit Blackstone Multi-Asset, which manages investment strategies in the form of hedge funds.

Banks typically use SRTs to buy protection against default on a pool of loans. This can be done through a traditional cash transaction where assets are moved into a special investment vehicle that issues bonds, or through a derivative product where the lender holds the assets on its balance sheet.

Asset managers and hedge funds, including Dutch pension fund PGGM (valued at $244 billion) and New York-based DE Shaw, were also among the largest buyers.

The market for these products first developed in Europe after the 2008 financial crisis, when lenders were asked to meet stricter regulatory capital requirements. US banks became more active last year after the Federal Reserve gave the green light to the capital relief deals.

The International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers estimates that there were 89 SRT transactions globally last year for loans worth a total of €207 billion. About 80 percent of these were corporate loans, with the remainder made up of debt such as subscription lines, auto loans and trade finance loans.

Although private equity credit facilities represent a small part of the SRT market, they have become popular because they are perceived as relatively safe.

“The thing about subscription lines is that it’s an asset class that historically has no losses,” said Frank Benhamou, risk transfer portfolio manager at Cheyne Capital. “They tend to be tightly priced, so investors who engage in this trade often use a little bit of leverage to enhance returns.”

SRTs expose Blackstone to the risk that large investors such as pension funds and sovereign wealth funds will refuse to meet capital calls when the loans mature, usually within a year. An investor could be left short of cash or face complications such as sanctions or fraud.

Although no limited partner has ever defaulted on its obligations, including during the 2008 financial crisis, potential buyers have been wary because of the lower diversification of subscription lines compared to corporate loans.

“While we accept that the credit risk for subscription lines is low, there is a risk that we cannot quantify and price,” said an investor who has been active in the SRT market for more than a decade.

The pool of loans for subscription lines is smaller than more traditional asset classes, so the “idiosyncratic risk is the sensitivity of your returns to one party… and there is a higher risk of fraud, which is difficult to estimate,” they added, referring to the limited number of private equity funds they would be exposed to.

Another SRT investor noted that a typical subscription line transaction involves anywhere from 10 to 30 funds, leading to more concentrated risk.

The rise of these debt products has also rekindled fears of unforeseen events, with banking analysts and some policymakers debating whether the banks selling the SRTs have fully protected themselves. In the April earnings call, Evercore ISI analyst Glenn Schorr asked Blackstone’s Gray whether the explosion of SRTs presented hidden risks, as it did during the global financial crisis.

These types of deals “give us the creeps, remind us of 16 years ago,” Schorr said, referring to the off-balance sheet entities banks used during the crisis to relieve their overstretched balance sheets. Gray said the firm conducted the transactions in a “responsible manner.”