A GROUP of scientists from the UK and Switzerland have created what they claim is the most difficult maze ever designed.

The team, led by physicist Felix Flicker from the University of Bristol, generated pathways called irregular repeating patterns.

The resulting mazes describe a bizarre form of matter known as quasicrystals.

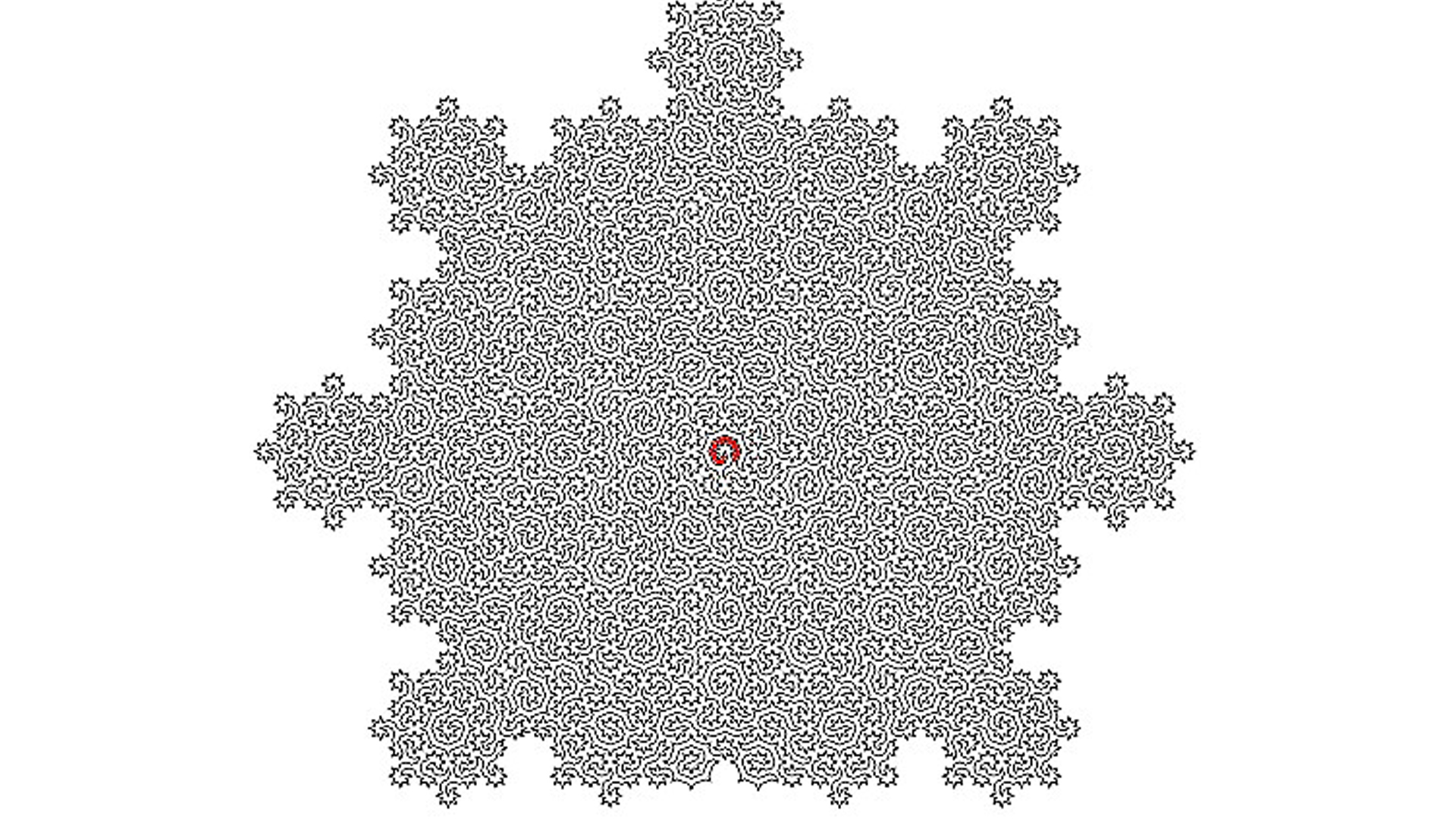

“When we looked at the shapes of the lines we constructed, we saw that they formed incredibly complex mazes,” Flicker explained in a press release.

“The size of the successive mazes grows exponentially – and there are infinitely many of them.”

The experiment was partly based on the movement of the knight across a chessboard.

In the so-called ‘knight’s march’ the piece visits each square of the chessboard only once before returning to the starting square.

This is known as a ‘Hamiltonian path’. The path runs through a graph, touching each vertex exactly once.

The physicists constructed infinite and ever-expanding Hamiltonian paths in irregular structures describing matter known as quasicrystals.

Quasicrystals are structurally somewhere between glass and regularly arranged crystals such as salt or quartz.

To return to the chess analogy, quasicrystal atoms occur in irregularly repeating and asymmetrical patterns, unlike a chessboard.

They are also extremely difficult to find. Only three natural quasicrystals have been found, all in the same meteorite.

The Hamiltonian paths form complex mazes with a clear starting point and an end. They may look complicated, but they are quite easy to solve.

But beyond being a form of entertainment, Flicker believes Hamiltonian cycles “can have practical purposes spanning several areas of science.”

The experimental results also show that quasicrystals can be efficient adsorbers.

The term describes the ability of solids to attract molecules or gases or solutions that touch them to their surface.

One application of adsorption is carbon capture and storage, preventing carbon dioxide molecules from entering the atmosphere.

“Our work also shows that quasicrystals can be better than crystals for certain adsorption applications,” said co-author Shobha Singh, a PhD candidate in physics at Cardiff University.

“For example, bendy molecules will find more ways to land on the irregularly arranged atoms of quasicrystals. Quasicrystals are also brittle, meaning they easily break apart into small grains. This maximizes their adsorption surface.”

Efficient adsorption could also make quasicrystals excellent candidates for use as catalysts, substances that lower the energy required to initiate a chemical reaction.

One possible application is the production of ammonia fertilizer for agriculture.

What is a quasicrystal?

Quasicrystals may appear symmetrical, but they are actually made up of irregularly repeating patterns.

Quasicrystals are a form of matter with atoms that are ordered, but not periodic.

This means that their pattern extends over the entire available space, but is not symmetrical.

In terms of structure, matter is somewhere between glass, which are known as amorphous solids, and crystals, which consist of neat and ordered patterns.

Quasicrystals appear to be formed from two different structures assembled in a non-repeating matrix,

They are rarely found in nature: three of them were found in a meteorite that fell in Russia’s Khatyrka region in 2011.

The third and final specimen was found in 2016 and was only a few micrometers wide.

It was discovered by a team of geologists led by Luca Bindi from the University of Florence in Italy.

Quasicrystals have also been created artificially, for example during the explosion of the first atomic bomb during the Trinity test in 1945.

The temperature and pressure of the explosion caused the surrounding sand to melt into a glassy material called trinitite.

In May 2021, scientists discovered a quasicrystal in a trinitite sample.