Prehistoric humans hunt a woolly mammoth. A growing body of research shows that this species—and at least 46 other megaherbivores—were driven to extinction by humans. (Source: Engraving by Ernest Grise, photographed by William Henry Jackson. Courtesy Getty’s Open Content Program)

AARHUS, Denmark — Imagine a world where elephants roamed Europe, giant ground sloths lumbered across the Americas, and car-sized armadillos settled in South American grasslands. This wasn’t a fantasy realm out of a Hollywood movie—this was the Earth of just 50,000 years ago. But then something happened. These megafauna—animals weighing more than 100 pounds—began to disappear. By 10,000 years ago, most were gone for good.

What caused this mass extinction that reshaped life on our planet? It’s a question that has puzzled scientists for more than 200 years. Now, an international team of researchers has conducted a thorough review of the evidence and concluded that prehistoric humans were likely the primary culprits behind the demise of Earth’s giants.

The study, led by scientists from the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO) at Aarhus University, analyzed patterns of megafauna extinctions across continents and time periods. They found that large animals began disappearing soon after humans arrived in new regions, with extinction rates highest where humans were most novel.

“The large and highly selective loss of megafauna over the past 50,000 years is unique in the past 66 million years. Previous periods of climate change did not lead to large, selective extinctions, arguing against a major role for climate in megafauna extinctions,” said Professor Jens-Christian Svenning, the study’s lead author, in a statement.

The researchers point out that climate change, long considered a possible cause of the extinctions, does not adequately explain the observed patterns. While the late Pleistocene did see significant climate shifts, they were no more extreme than earlier glacial cycles that did not lead to mass extinctions.

“Another important pattern arguing against a role for climate is that recent megafauna extinctions hit just as hard in climatically stable areas as in unstable areas,” Svenning adds.

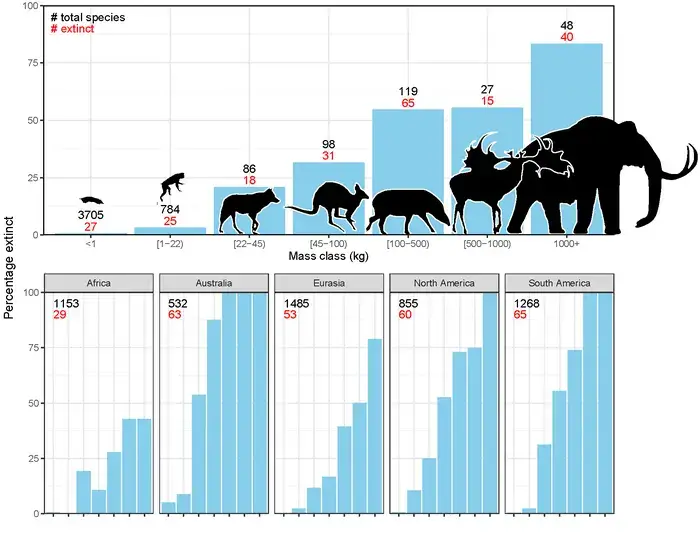

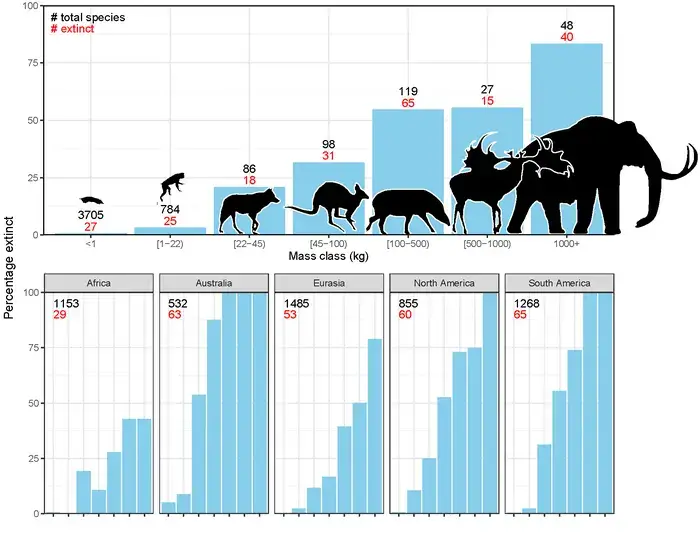

Furthermore, megafauna losses were highly selective, affecting only the largest species. Smaller animals, plants, and marine life were largely unaffected. This size bias is consistent with what we would expect from human hunting pressure, not climate change.

The study found that at least 161 species of mammals went extinct during this period, based on the remains found so far. The largest animals were hit hardest: land-dwelling herbivores that weighed more than a ton, known as megaherbivores. Fifty thousand years ago, there were 57 species of megaherbivores. Today, only 11 remain, and even these survivors are facing dramatic population declines.

Interestingly, regions where humans had a longer evolutionary history with large animals saw less severe extinctions. In Africa and parts of Asia, where hominins had been present for millions of years, fewer megafauna species went extinct compared to the Americas and Australia. This suggests that animals in Africa and Asia evolved behaviors over time to avoid human predators. The researchers found evidence of human hunting skills in the archaeological record.

“Early modern humans were effective hunters of even the largest species and clearly had the ability to reduce populations of large animals,” Svenning notes. “These large animals were and are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they have long gestations, produce few offspring at a time, and take many years to reach sexual maturity.”

The loss of these ecosystem giants had a profound impact that continues to shape our world today. Large herbivores such as mammoths and ground sloths played a crucial role in maintaining open habitats and spreading nutrients across landscapes. Their disappearance likely contributed to the spread of forests and changes in fire regimes in many regions.

“Species became extinct on all continents except Antarctica and in all types of ecosystems, from tropical forests and savannas to Mediterranean and temperate forests and steppes to Arctic ecosystems. Many of the extinct species were able to thrive in different types of environments. Therefore, their extinction cannot be explained by climate changes that caused the disappearance of a specific ecosystem type, such as the mammoth steppe – which also housed only a few megafauna species,” Svenning emphasizes.

The authors argue that understanding this extinction event is crucial, as we face a biodiversity crisis today. By recognizing the long history of humans influencing animal populations, we can better address conservation concerns. They even suggest “rewilding,” the reintroduction of large animals to restore lost ecological functions, as a possible conservation strategy.

“Our results emphasize the need for active conservation and restoration efforts. By reintroducing large mammals, we can help restore the ecological balance and support the biodiversity that evolved in megafauna-rich ecosystems,” Svenning concludes.

The research was published in the journal Cambridge Prisms: Extinction.

Methodology

The researchers conducted an extensive literature review, examining evidence from paleontology, archaeology, genetics, and ecology. They analyzed patterns of megafauna extinctions on different continents, at different time periods, and across different body size classes. The team also evaluated different hypotheses for the extinctions, including climate change and human impacts, against the observed patterns. Their review covered several areas of research, including studies of the timing of species extinctions, dietary preferences of animals, climate and habitat requirements, genetic estimates of past population sizes, and evidence of human hunting.

Results

The study found that megafauna extinctions were global in scale but varied in intensity by region. They were strongly biased toward the largest species and temporally linked to the arrival of humans in new areas. The extinctions were not well explained by climate change alone. The researchers found that at least 161 mammal species were driven to extinction during this period, with land-dwelling herbivores weighing more than a ton (megaherbivores) being hit the hardest.

Limits

One potential limitation of this study is that the fossil record is incomplete, especially for smaller species, which may affect our understanding of extinction patterns. The dating of extinction events and human arrivals can be imprecise, making it difficult to establish precise temporal relationships. Furthermore, complex interactions between people, climate, and ecosystems are difficult to fully disentangle, especially over such long timescales.

Discussion and conclusions

The researchers conclude that human hunting and ecosystem modification were likely the primary drivers of megafauna extinctions in the late Quaternary. They argue that this event is an early example of human-induced environmental change on a global scale. The study emphasizes that humans have been shaping ecosystems for tens of thousands of years and that large animals are particularly vulnerable to human impacts. The loss of megafauna had cascading effects on landscapes and ecosystems, with changes in vegetation structure, seed dispersal patterns, and nutrient cycling. The authors emphasize the importance of understanding past extinctions to inform modern conservation efforts. They suggest that rewilding with large animals could help restore lost ecological functions and support biodiversity in ecosystems that evolved with megafauna.