By means of

This is an artist’s rendering of a Hyper-X research vehicle under scramjet power in free flight after separating from its booster rocket. New research into hypersonic jets could transform space travel by making scramjet engines more reliable and efficient, leading to aircraft-like spacecraft. Credit: NASA

Wind tunnel research reveals that hypersonic jet engine flow can be controlled optically

Researchers at the University of Virginia are exploring the potential of hypersonic jets for space travel, using innovations in engine control and sensing techniques. The work, supported by NASAaims to improve the performance of scramjets through adaptive control systems and optical sensors. This could lead to safer and more efficient spacecraft that function like airplanes.

The future of space travel: hypersonic jets

What if the future of space travel looked less like Space-X’s rocket-based Starship and more like NASA’s “Hyper-X,” the hypersonic jet that, 20 years ago this year, flew faster than any other aircraft before or after?

In 2004, NASA’s final X-43A unmanned prototype tests marked a milestone in the latest era of jet development—the leap from ramjets to faster, more efficient scramjets. The final test, in November of that year, recorded a world-record speed that only a rocket had previously achieved: Mach 10. The speed is equal to 10 times the speed of sound.

NASA gathered a lot of useful data from the tests, as did the Air Force six years later in similar tests with the X-51 Waverider, before the prototypes crashed into the ocean.

Although the hypersonic proof of concept was successful, the technology was far from operational. The challenge was achieving engine control, as the technology was based on decades-old sensor approaches.

NASA’s B-52B launch vehicle flies to a test range over the Pacific Ocean on November 16, 2004, carrying the third and final X-43A vehicle, attached to a Pegasus rocket. Photo: NASA/Carla Thomas

Breakthroughs in hypersonic engine control

However, this month there was hope for possible successors to the X-plane series.

As part of a new NASA-funded study, researchers from the University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science published data in the June issue of the journal Aerospace science and technology which showed for the first time that the airflow in supersonic combustion jet engines can be controlled by an optical sensor. The finding could lead to more efficient stabilization of hypersonic jets.

In addition, the researchers achieved adaptive control of a scramjet engine, which was another first in the field of hypersonic propulsion. Adaptive engine control systems respond to changes in dynamics to maintain optimal overall system performance.

“One of our national priorities in aerospace since the 1960s has been to build single-stage aircraft that can fly into space from a horizontal takeoff like a traditional airplane and land on the ground like a traditional airplane,” said Professor Christopher Goyne, director of the UVA Aerospace Research Laboratory, where the research took place.

“The most advanced vessel currently is the SpaceX Starship. It has two stages, with vertical launch and landing. But to optimize safety, convenience and reusability, the aerospace community wants to build something that looks more like a 737.”

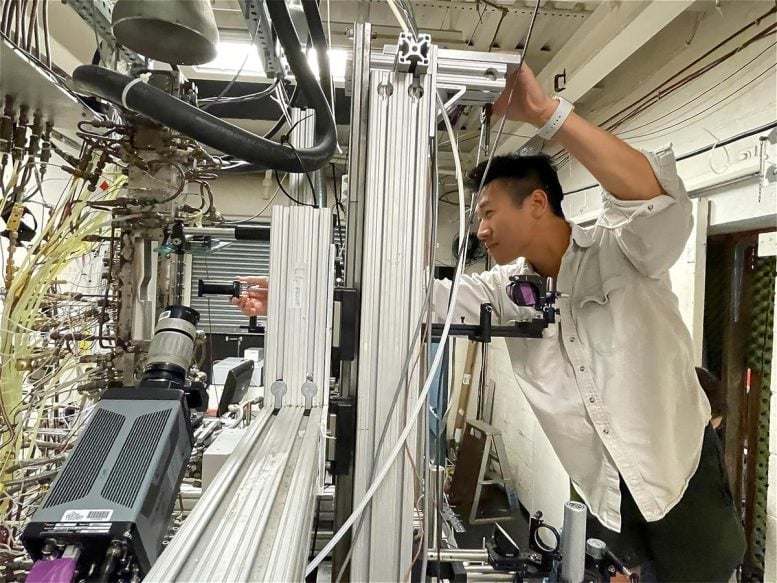

PhD candidate Max Chern examines the wind tunnel setup where researchers from the University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science demonstrated that control of a dual-mode scramjet engine is possible with an optical sensor. Credit: Wende Whitman, UVA Engineering

Goyne and his co-researcher, Chloe Dedic, an associate professor of engineering at UVA, believe that optical sensors could play an important role in control engineering.

“It seemed logical to us that if an aircraft is operating at hypersonic speeds of Mach 5 and higher, it would be better to incorporate sensors closer to the speed of light than to the speed of sound,” Goyne said.

Other members of the team included doctoral student Max Chern, who was the first author of the paper, as well as former graduate student Andrew Wanchek, doctoral student Laurie Elkowitz and UVA senior scientist Robert Rockwell. The work was supported by a NASA ULI grant led by Purdue University.

Improving Scramjet engine performance

NASA has long sought to prevent something that can occur in scramjet engines called “unstart.” The term refers to a sudden change in airflow. The name comes from a specialized testing facility, a supersonic wind tunnel, where a “start” means that the wind has reached the desired supersonic conditions.

UVA has several supersonic wind tunnels, including the UVA Supersonic Combustion Facility, which can simulate engine conditions for a hypersonic vehicle traveling five times the speed of sound.

“We can run test conditions for hours, allowing us to experiment with new flow sensors and control methods on realistic engine geometry,” Dedic said.

Goyne explained that “scramjets,” short for supersonic burner ramjets, build on ramjet technology that has been in common use for years.

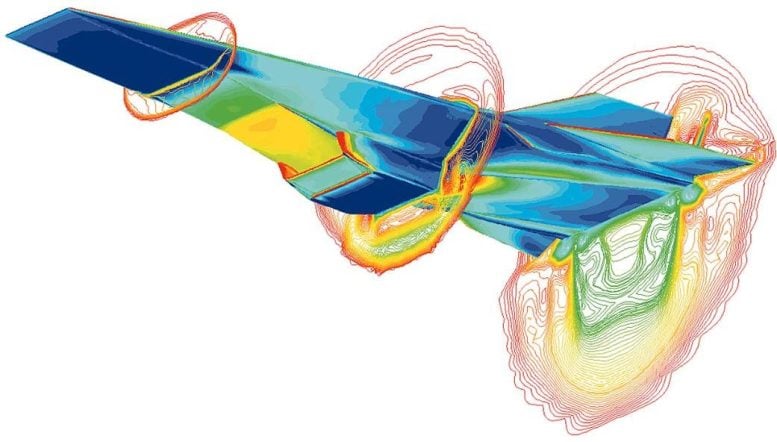

This numerical fluid dynamics image from the original Hyper-X tests shows the engine running at Mach 7. Credit: NASA

Ramjets essentially “ram” air into the engine using the forward motion of the aircraft to generate the temperatures and pressures needed to burn fuel. They operate in a range of approximately Mach 3 to Mach 6. As the intake at the front of the craft narrows, the internal airspeed slows to subsonic speeds in a ramjet internal combustion engine. However, the plane itself does not do that.

Scramjets are a little different though. While they are also “air breathing” and have the same basic layout, they need to maintain that super fast airflow through the engine to reach hypersonic speeds.

“If something happens within the hypersonic engine and subsonic conditions suddenly arise, that is a moot point,” says Goyne. “The thrust will drop suddenly and it may be difficult to restart the intake at that point.”

Testing a dual-mode scramjet engine

Currently, scramjet engines, like ramjets, require boost to get them up to a speed where they can take in enough oxygen to operate. That could be a ride attached to the underside of an aircraft carrier, or it could be a rocket boost.

The latest innovation is a dual-mode scramjet combustion engine, the type of engine tested by the UVA project. The dual engine starts in ramjet mode at lower Mach numbers and then switches to receiving a full supersonic airflow into the combustion chamber at speeds above Mach 5.

Preventing no-starts while the engine is making that transition is critical.

Christopher Goyne, professor and director of the UVA Aerospace Research Laboratory, and Chloe Dedic, associate professor. Credit: Wende Whitman, UVA Engineering

The incoming wind interacts with the inlet walls in the form of a series of shock waves known as a ‘shock train’. Traditionally, the leading edge of these waves, which can be destructive to the integrity of the aircraft, is monitored by pressure sensors. For example, the machine can adjust by moving the position of the shock train.

But where the leading edge of the shock train is can change quickly as flight disturbances change the dynamics in the air. The shock train can pressurize the intake, creating conditions for a start.

So, “If you’re observing at the speed of sound and the motor processes are moving faster than the speed of sound, you don’t have much reaction time,” Goyne said.

He and his associates wondered whether an impending start-up could be predicted by observing the properties of the engine flame instead.

Feeling the spectrum of a flame

The team decided to use an optical emission spectroscopy sensor to provide the feedback needed to control the leading edge of the shock train.

No longer limited to information obtained at the walls of the engine, such as pressure sensors, the optical sensor can identify subtle changes both within the engine and within the flow path. The tool analyzes the amount of light emitted by a source — in this case, the reacting gases within the scramjet combustion chamber — and other factors such as flame location and spectral content.

“The light emitted by the flame in the engine is due to the relaxation of the molecules kind “These are excited during combustion processes,” explained Elkowitz, one of the PhD students. “Different types emit light at different energies or colors, which provides new information about the state of the engine that is not captured by pressure sensors.”

Current UVA Engineering mechanical engineering and aerospace doctoral students Laurie Elkowitz and Max Chern were among the influential members of the team. Credit: Wende Whitman, UVA Engineering

The team’s wind tunnel demonstration showed that the engine control can be both predictive and adaptive, and can switch smoothly between scramjet and ramjet functions.

The wind tunnel test was in fact the world’s first proof that adaptive control in this type of dual-function motorcycle can be achieved with optical sensors.

“We were very excited to demonstrate the role that optical sensors could play in the control of future hypersonic vehicles,” said first author Chern. “We continue to test sensor configurations as we work on a prototype that optimizes package volume and weight for flight environments.”

Building the future

Although much work remains to be done, Goyne thinks optical sensors could be part of the future that will be realized within his lifetime: an airplane-like journey to space and back.

Dual-mode scramjets would still require some kind of boost to get the plane to at least Mach 4. But there would also be an added safety measure, namely not relying solely on rocket technology, which requires carrying highly flammable fuel as well as large amounts of chemical oxidizer to burn off the fuel.

That lower weight would create more space for passengers and cargo.

Such an all-in-one aircraft, which would one day float back to Earth like the space shuttles, could even offer the ideal combination of cost-efficiency, safety and reusability.

“I think it’s possible, yes,” Goyne said. “While the commercial space industry has been able to reduce costs through some reusability, they haven’t yet mastered aircraft-like operations. Our findings could potentially build on the storied history of Hyper-X and make access to space safer than current rocket-based technology.”

Reference: “Monitoring a Dual-Mode Scramjet Current Path Using Optical Emission Spectroscopy” by Max Y. Chern, Andrew J. Wanchek, Laurie Elkowitz, Robert D. Rockwell, Chloe E. Dedic, and Christopher P. Goyne, April 18, 2024 , Aerospace science and technology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ast.2024.109144