The return to Earth of Boeing’s Starliner capsule is on hold indefinitely pending the results of new thruster tests and continued analysis of helium leaks that emerged during the ship’s rendezvous with the International Space Station, NASA said Friday.

But agency officials continued to insist that Starliner commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams are not “stranded” in space.

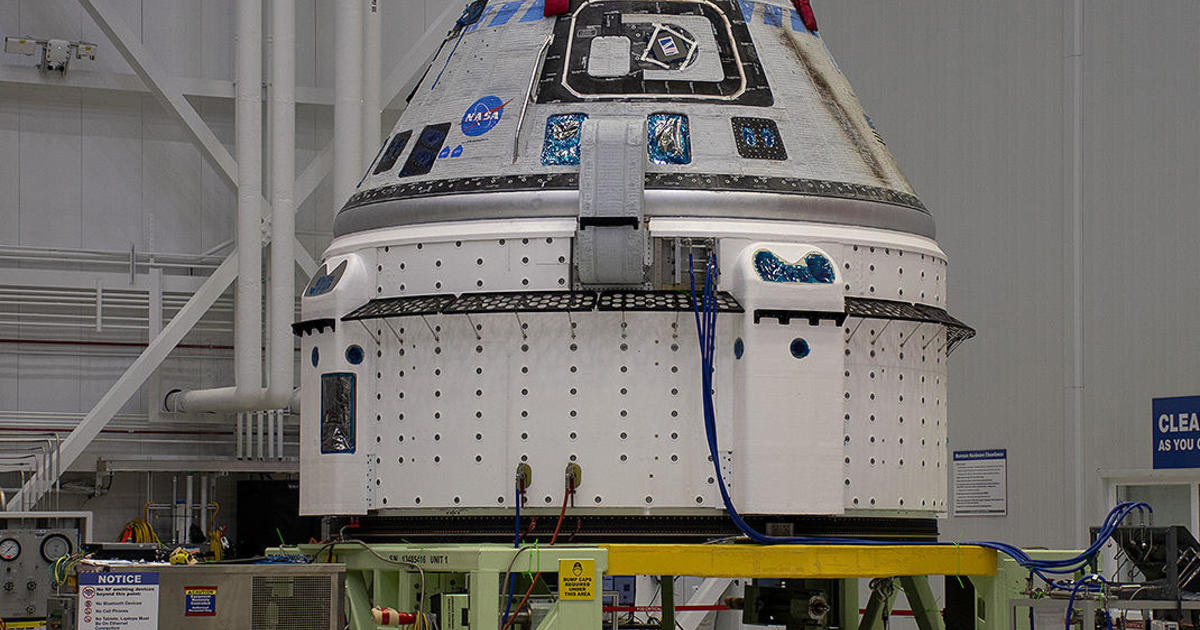

NASA

“We don’t have a target (landing) date as of today,” Steve Stich, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program Manager, told reporters on a conference call. “We’re not going to give a specific date until we complete that test.

“So essentially it’s completing the testing, completing the fault tree, taking that analysis to (the mission management team) and then having an agency-level review. And then we’ll lay out the rest of the plan, from undocking to landing. I think we’re on the right track.”

The problem for NASA and Boeing is that the Starliner’s service module, which houses the helium lines, thrusters and other critical systems, is discarded and burns up in the atmosphere before reentry.

Engineers won’t be able to study the hardware afterwards, so they want to collect as much data as possible before Wilmore and Williams go home.

But the crew’s repeatedly extended stays on the space station while that analysis continued has led some observers to say that Wilmore and Williams are stranded in orbit, a perception that seems to have taken root in the lack of updates from NASA as the target landing date was repeatedly pushed back.

Stich and Mark Nappi, Boeing’s Starliner program manager, said that description is a mischaracterization.

“It’s pretty painful to read all the stuff that’s coming out,” Nappi said. “We had a really good test flight … and it’s being looked at pretty negatively. We’re not stuck on the ISS. The crew is not in danger and there’s no increased risk if we decide to bring Suni and Butch back to Earth.”

Stich added that he “wants to make it very clear that Butch and Suni are not stranded in space. Our plan is to return them on Starliner and bring them back home at the right time. We’ll do some more work have to do to get there for the final return, but they are safe on the space station. Their spacecraft is working well and they are enjoying their time on the space station.

The Starliner was launched on June 5 on the program’s first crewed test flight with one known helium leak. The other four were created during the ship’s rendezvous with the space station when the jets were rapidly pulsed to fine-tune the Starliner’s approach.

United Launch Alliance

While docked at the station, the valves are closed to isolate the helium system, eliminating additional leakage. But once Wilmore and Williams leave and go home, the valves are opened again to repressurize the lines or manifolds.

Stich said that even with the known leaks, the spacecraft will have 10 times as much helium as it needs to get home, but engineers want to make sure the leaks don’t get worse once the system is repressurized.

The five aft thrusters in the Starliner’s service module also did not function as expected during the space station’s approach on June 6.

After docking, four of the five jets were tested successfully and despite slightly lower power levels than expected, they are considered good for undocking and reentry. The fifth thruster was not “hot fired” because its previous performance indicated that it had actually failed.

But managers want to find out what caused the other four to behave unexpectedly. Starting next week, a new thruster, identical to the one aboard the Starliner, will be tested at a government facility in White Sands, New Mexico, just as the thrusters fired in space during the Starliner’s rendezvous and docking.

“We will recreate that profile,” Stich said. “Then we will put quite an aggressive profile in the thruster for the (disengage to re-enter) phase.”

NASA

It is possible that the problems with the rear-facing thrusters were caused by higher-than-normal temperatures due to the Starliner’s orientation relative to the sun, or the series of rapid, repetitive firings commanded by the flight software. Or both.

The ground tests, which are expected to take “a couple of weeks,” could potentially provide evidence for one side or the other.

“This is a real opportunity to examine a thruster like we’ve had in space on the ground, a detailed inspection,” Stich said. “Once that test is completed, we will look at the landing plan.”

As for the perception that the crew is stranded in space, Stich and Nappi both pointed out that a catastrophic “event” occurred on Wednesday when a malfunctioning Russian satellite in a slightly lower, more tilted orbit than the space station did, killing more than 100 pieces of traceable debris have been produced.

As flight controllers evaluated the wreckage’s trajectories, the space station’s nine-member crew was told to shelter aboard their respective spacecraft, ready to depart immediately and return to Earth in the event of a damaging impact.

Two Russian cosmonauts and NASA’s Tracy Dyson boarded their Soyuz ferry, while three NASA astronauts and another cosmonaut floated in their SpaceX Crew Dragon. Wilmore and Williams rode to a safe haven in the Starliner and were cleared to fly home if warranted.

After about an hour, the crew was signaled to return to normal operations. If the Starliner had been deemed unsafe, Wilmore and Williams would likely have been told to seek refuge in the Crew Dragon. But that was not the case.

“We have an approval to serve as a rescue boat in case of emergency on ISS,” Nappi said. “That means we can return with the Starliner at any time, and that has been proven this week.”