Hundreds of millions of years ago, trilobites were everywhere on Earth. Clad in tough exoskeletons, the animals left behind countless fossils that can be studied by paleontologists today. Despite all these preserved shells, scientists have not been able to understand certain aspects of trilobite anatomy after centuries of research, especially the soft internal structures of the ancient arthropods.

But a group of trilobite fossils buried in volcanic ash in Morocco may offer the best insight yet into the segmented navigators. In a paper published Thursday in the journal Science, researchers describe a group of trilobites that were fossilized in a similar way to the Romans of Pompeii who were frozen by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Abderrazak El Albani, a geologist at the University of Poitiers in France, led the dig that led to the discovery of the new fossils in the High Atlas Mountains in 2015. During the Cambrian period, 510 million years ago, the area was a shallow marine environment surrounded by spewing volcanoes. One of those eruptions left behind a creamy-colored layer of fine-grained volcanic ash in which the trilobites were fossilized.

When the researchers broke open the volcanic rock, they found incredibly detailed impressions of the trilobites etched into the stone. “Volcanic ash is so fine-grained, like talcum powder, that it can form the smallest anatomical features on the surfaces of these animals,” said John Paterson, a paleontologist at the University of New England in Australia and one of the co-authors of the new study . study.

Dr. El Albani and his team hypothesize that a short and sudden burst of volcanic activity buried the trilobites as ash-like debris flooded the marine environment. In fact, a suffocated trilobite’s digestive tract is full of sediment that it may have ingested before dying. When the ash turned to stone, it created three-dimensional molds of the buried trilobites.

This froze the trilobites in time, much like the doomed inhabitants of Pompeii, who were buried in ash as they fled the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Some trilobites are curled up in a ball, while others look like they are about to run around. One specimen is even covered with tiny bivalves, which have hitched a ride on the animal’s shell with the help of fleshy stems.

“These brachiopods are still in their life position, which shows how quickly the burial took place,” said Dr. El Albani.

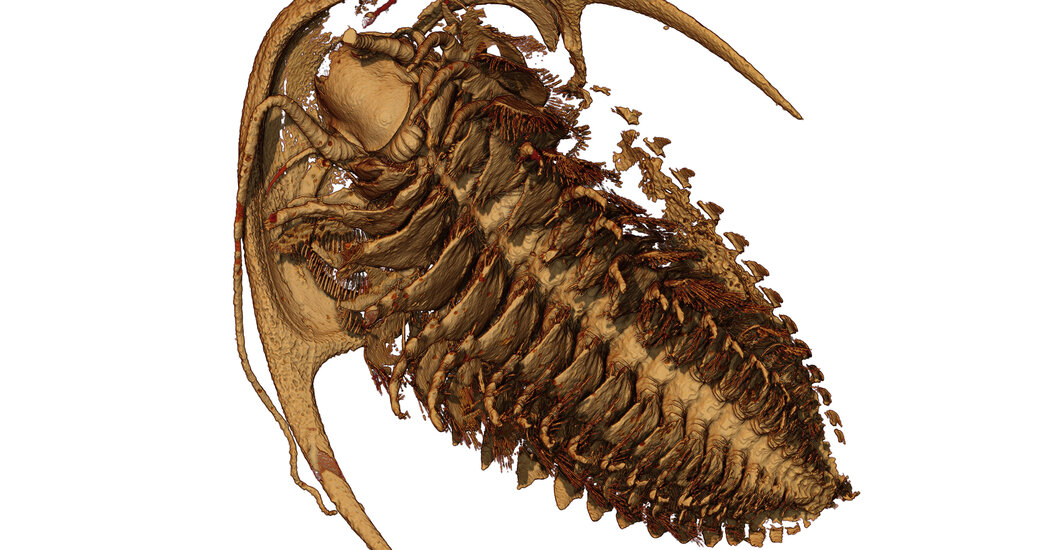

To get a better look at the fossilized anatomies, the scientists used micro-CT scans and X-ray images to create 3D images of the specimens. This allowed them to view delicate structures such as antennae, digestive tracts and even the hair-like bristles on the trilobites’ walking legs.

The team also discovered previously unknown anatomical features. These included several small appendages that helped scoop food into the trilobite’s slit-like mouth, and a flap of soft tissue called a labrum that attached to the trilobite’s hard mouthpart and is now a common feature among living arthropods.

“The labrum is a kind of fleshy lip that is connected to the mouth and is part of the oral chamber where food is processed,” Dr. Paterson said. “The labrum has long been thought to exist in trilobites, but it has never been seen in the fossil record.”

According to Thomas Hegna, a paleontologist at the State University of New York at Fredonia who was not part of the study, the appendages seen in the new specimens were most likely not shared in the same form by all trilobites. For example, some insect-eyed species in the genus Carolinites would have had to “drag their eyes through the mud with their feet,” which were as short as those on the Moroccan specimens, he said.

But the intricate structures preserved in these “breathtaking” specimens will help place trilobites in the arthropod family tree, he says.

“This is going into the details of anatomy, but such debates are relevant if we want to figure out which group of living arthropods is most closely related to extinct trilobites,” he said.

For Dr. El Albani, a Moroccan, the incredible trilobite specimens also represent something more than a taxonomic tool. He hopes they will lead to greater protection of Morocco’s paleontological heritage, which is so exploited by commercial fossil traders that some call it a “trilobite economy.”

“We want to protect the place where the discovery was made to make it available to science,” he said.