Nowhere in the world have private equity firms found a more hospitable environment than in the UK: the scale of takeovers over the past two decades has had a greater impact on the overall economy than in any other developed market, including the US, where the sector has emerged, data shows.

Private equity firms have acquired household names, from grocers Asda and Morrisons to sandwich chain Pret A Manger, and invested in sectors ranging from insurance to nursing homes and infrastructure.

Now their track record and comparatively low taxes are coming under renewed scrutiny ahead of next week’s election. The poll-topping Labour Party wants to raise taxes on the performance fees that fund managers receive from asset sales (“carried interest”), raising concerns that dealmakers could be tempted to move elsewhere.

How quickly did the private equity industry grow?

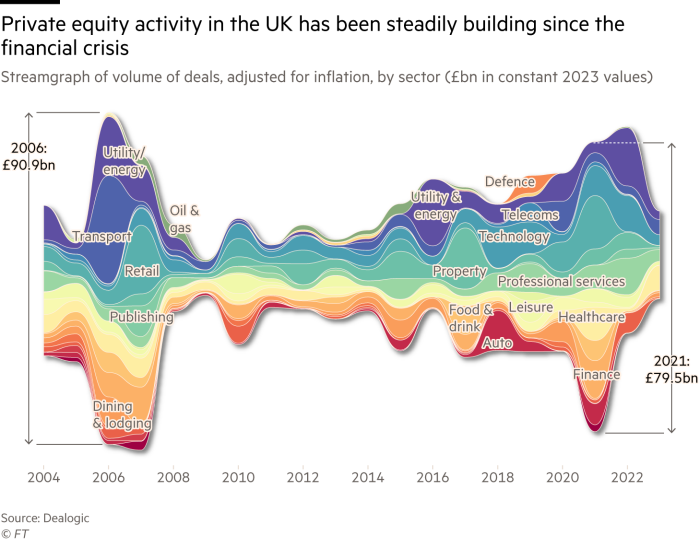

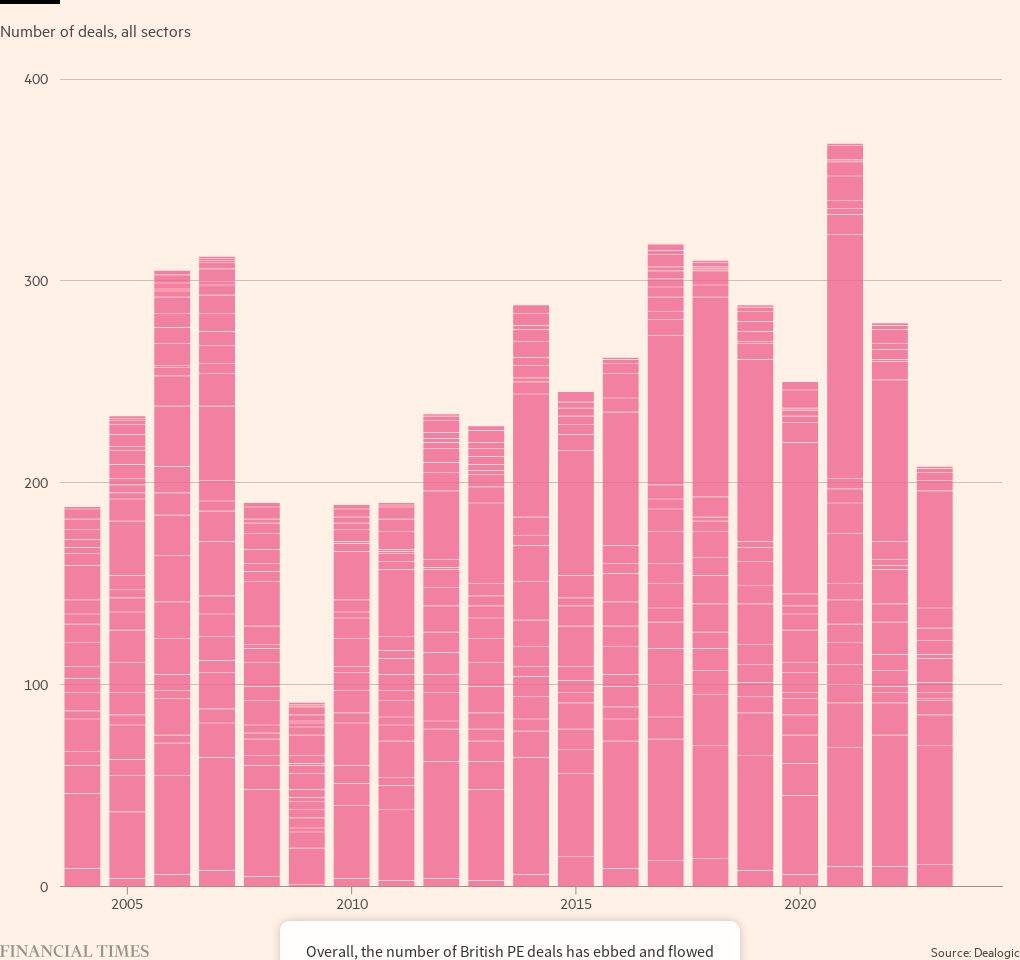

British-based private equity groups followed in the footsteps of American buyout pioneers, including KKR, in the 1990s by raising funds from pension and sovereign wealth funds to target British and European companies. The total value of private equity transactions peaked at £91 billion in 2006.

The global financial crisis around 2007 and 2008 cooled activity, with private equity investors shifting their focus from sectors such as transportation to technology and professional services.

But over the past two decades, deals have made up a larger share of the economy than in the US or other European markets, according to data from Dealogic, with London becoming a European hub. Over time, thousands of investors and associated service providers also chose the City of London as their base.

What are the largest private equity firms in Britain?

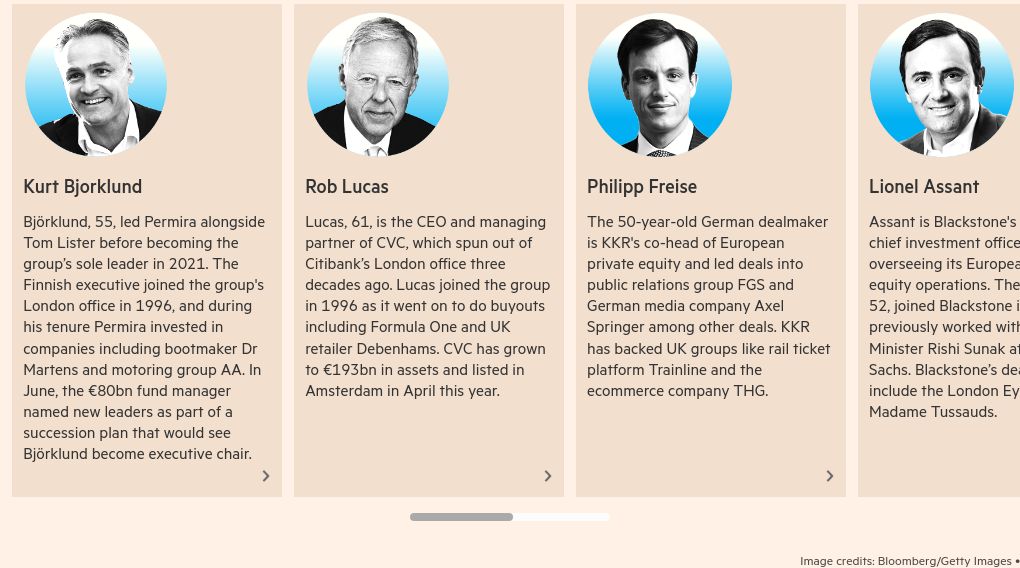

Top buyout groups such as CVC, Permira, Cinven and Apax are based or have their largest offices in London, while US groups such as KKR, Blackstone, Apollo and Clayton, Dubilier & Rice have established their main European outposts in the British capital. These typically finance the largest deals with some of their largest investors, including sovereign wealth funds, such as GIC, and pension funds, such as the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board.

Blackstone, the world’s largest alternative investor by assets under management, has been the most active, including through its real estate arm. The group’s senior European private equity manager Lionel Assant and recently knighted founder Stephen Schwarzman have a close relationship with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

Which sectors do buyout groups focus on?

While the industry’s early years were marked by large-scale acquisitions in sectors such as consumer goods and retail, dealmakers have recently shifted their focus to real estate and healthcare.

Technology, especially software with its reliable recurring sales, has also become an investor favorite for its resilience and growth.

However, the large transactions in other sectors have shaped public perception of the sector. The problems faced by Thames Water, Britain’s largest water company previously owned by Macquarie, and previous crises at private equity-owned care homes were among the events that darkened PE’s reputation. In 2007, private equity bosses were hauled before parliamentary committees, where they admitted mistakes in handling deals.

Here are the most important private equity deals in Britain over the past twenty years:

Who are the men in charge?

The leadership of Britain’s largest private equity firms is male-dominated and international. Although the sector is relatively small in terms of the number of people employed in it – law firm Macfarlanes estimated that only 2,550 people received interest – it is a valuable source of fees for law firms, banks and consultancies. The number of employees affected by private equity is in the millions when portfolio company executives are included.

“There are real benefits to having such a large industry presence here,” argues Michael Moore, head of industry lobby group British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association.

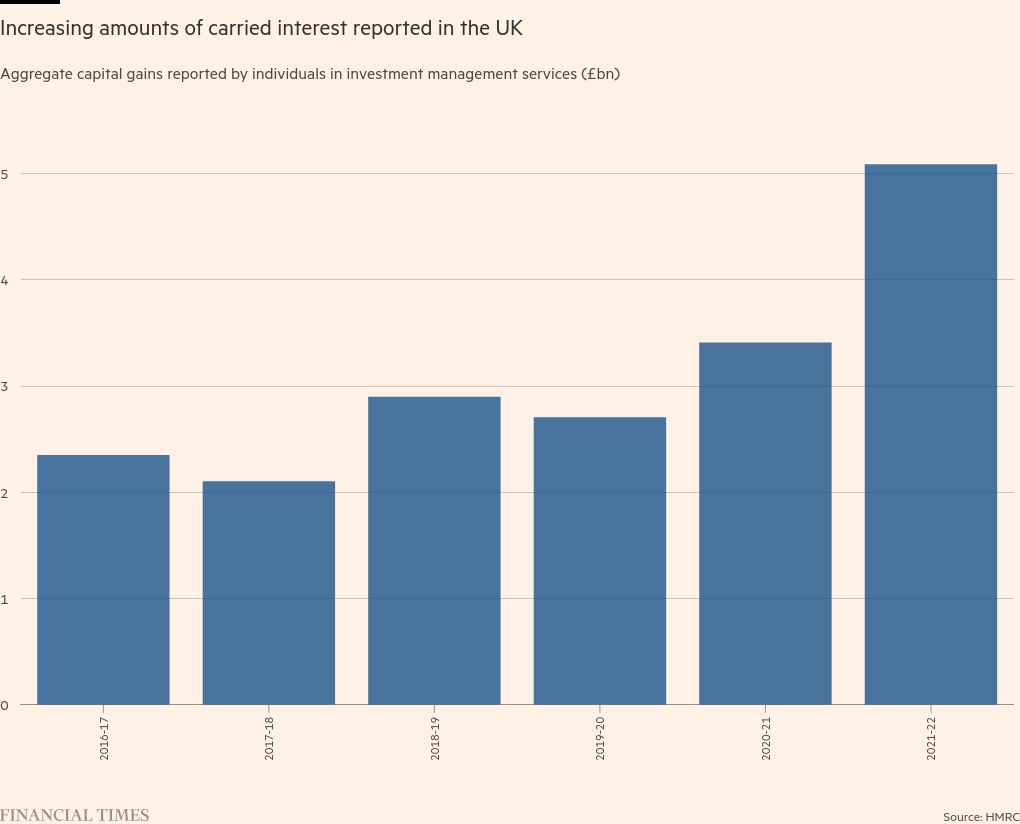

How much carry have private equity firms received?

Carried interest, which typically amounts to 20 percent of the profits that buying groups generate when they sell investments, has soared, fueled by a long period of cheap debt financing. During the pandemic years of 2021 to 2022, British buyout managers, spurred by low interest rates, massive state support and a flurry of transactions, saw their incentive fees rise above £5 billion.

Labour’s plan to increase taxes on these allowances and go beyond a planned Tory crackdown on the favorable ‘non-dom’ tax regime for expats has left the sector uneasy. Labor expects to raise a modest £565m a year by closing the ‘loophole’.

The BVCA has warned the Labor Party that it will tax carried interest as ordinary income – at the marginal rate of 45 percent – from lower-taxed capital gains, and that this risks luring dealmakers abroad.

Not all industry participants share this alarmist assessment. Ludovic Phalippou, a professor at Oxford’s Saïd School of Business who has documented the meteoric rise of private equity billionaires, says that while a few executives might leave to reduce their tax burden, funds would continue to invest in Britain .

There are also signs that shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves could soften the blow. She suggested earlier this month that buyout managers investing in their funds would continue to enjoy favorable tax treatment – putting Britain on par with France or Italy.

The industry welcomed the comment as “encouraging”. But the debate comes on top of new challenges for the private equity business model, which must continue to justify its high fees by delivering market-beating returns.

This becomes more difficult as interest rates rise because it limits the ability to finance buyouts with debt. A slowdown in the number of deals and listings, due to political uncertainty in Europe, has also made it harder to return capital to investors.

While the past two decades have been lucrative for these companies, “it’s not at all clear that they can repeat that in the future,” says Phalippou.

Data visualization and analysis by Patrick Mathurin and Alan Smith