It didn’t go perfectly.

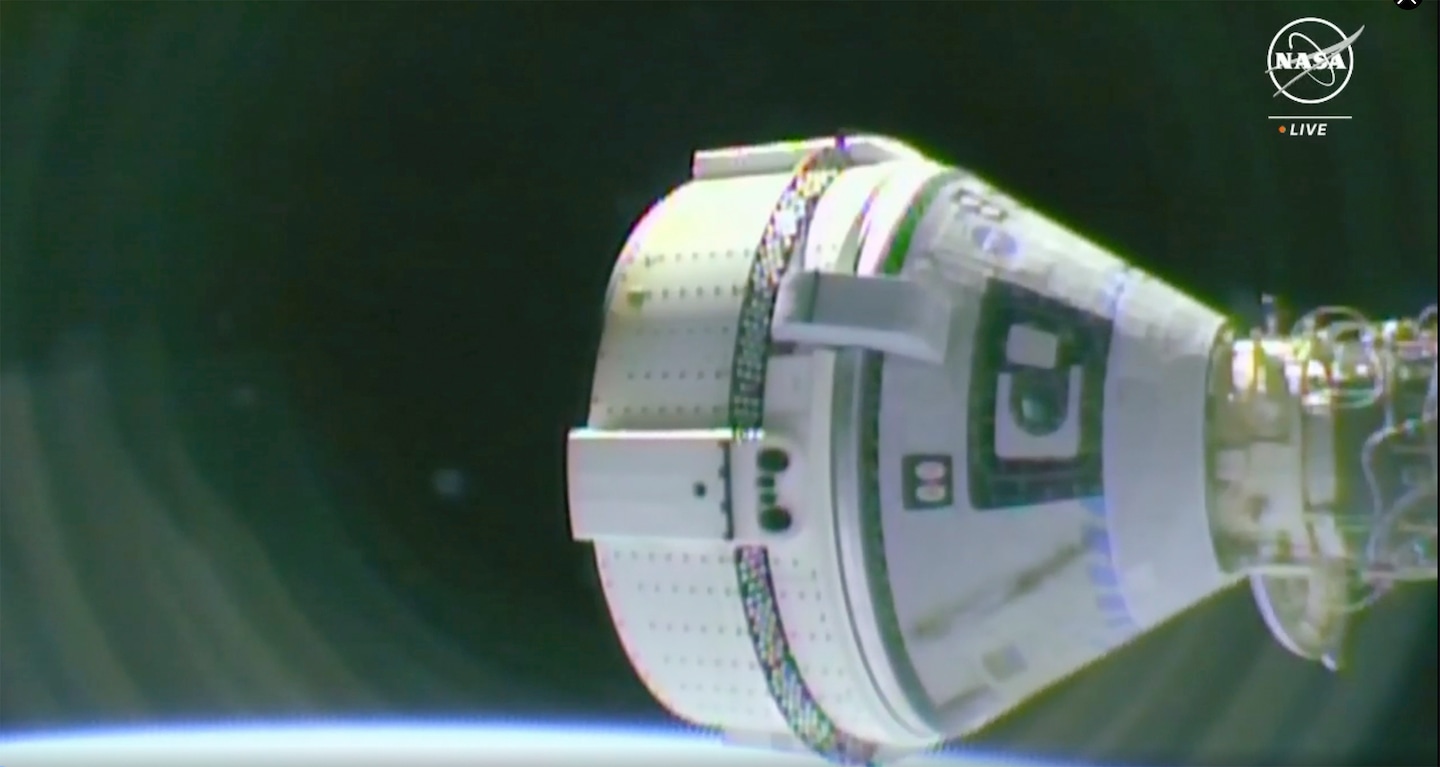

Instead of arriving home in about eight days, the spacecraft remains docked to the space station, with its return postponed indefinitely while teams continue to fix a series of problems — helium leaks and a pair of thrusters that fail at a critical time during the flight no longer works – in the capsule’s propulsion system.

While the top priority is ensuring NASA astronauts Sunita Williams and Barry “Butch” Wilmore return safely to Earth, the technical delays, and whether Boeing can overcome them, reflect more than just the high stakes for the Starliner’s future program, but also the expectations of the company. future in space. Boeing urgently needs to demonstrate that it can safely fly astronauts and overcome the kinds of technical challenges facing the spacecraft — as well as the company’s commercial aviation division.

Once the mission is complete, so should NASA and Boeing undergo a rigorous process to certify Starliner for regular crew rotation missions with a full contingent of four astronauts for a regular six-month stay on station. Only then is that possible Starliner joins SpaceX’s Dragon, which flew astronauts for NASA for the first time in 2020, and delivers on a $4.2 billion contract that NASA awarded to Boeing a decade ago.

NASA wants Boeing’s Starliner to serve as a second U.S. transportation system to the space station. SpaceX has been the sole provider since 2020, but NASA says it needs two systems in case one fails.

Years of setbacks, including a failed test flight without astronauts on board in 2019, have cost Boeing about $1.5 billion in cost overruns. It needs Starliner to start flying the regular rotational flights with crew so it can get paid for the missions.

“I have a lot of confidence that they are looking at it very hard and that they are not going to commit to dismantling a spacecraft that was unsafe,” said Wayne Hale, the former NASA Space Shuttle program director who also served as flight director. director for 40 shuttle flights. “Both Boeing and SpaceX make their money from the post-certification missions. Those are income flights. They are keen to recoup their development costs and essentially make a profit from the exercise. So it is important.”

GET SAVED

Stories to keep you informed

Starliner has caused a series of small helium leaks that have confused NASA and Boeing and led to a number of delays in getting off the ground and then home. Originally, the teams said they thought the leaks were due to a poor seal, but later said they weren’t sure what was behind it. They are also trying to determine why five of the spacecraft’s small thrusters suddenly stopped working as the spacecraft approached the space station on June 6, forcing NASA to have Boeing back up the vehicle and fire the thrusters again to bring them back online.

Initially, Starliner was scheduled to arrive home on June 18; then NASA pushed that back to June 26. The space agency postponed it again on Friday until sometime later in July, saying teams needed more time to study problems with the propulsion system.

There’s no rush to fly the astronauts home, NASA said; the helium leaks do not pose a risk to returns, the report said. Four of the five thrusters are now operating normally, and since the spacecraft is equipped with 28 such thrusters, there is plenty of redundancy, officials say. The spacecraft can remain in orbit for up to 45 days, giving crew members some breathing room to continue troubleshooting.

NASA and Boeing have repeatedly emphasized that Starliner is healthy and can be used at any time to fly the astronauts back to Earth in the event of an emergency on the space station.

“We are taking our time and following our standard mission management team process,” Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, said in a statement. “We are letting the data drive our decision-making regarding management of the small helium system leaks and thruster performance we observed during the rendezvous and docking.”

Being able to solve the thruster problem and the helium leaks will figure prominently in that certification review, officials say.

“We need to address the helium leaks,” Stich said during a media briefing last week. “We’re not going to fly another mission like this with the helium leaks.” The teams also need to figure out what “causes the thrusters to have low thrust,” he added. “So we still have some of that work to do after this flight.”

However, the certification process is not the agency’s primary concern at this time. For now, “the entire team is focused on understanding what happens to this vehicle for the manned flight test and our plan for return. So we didn’t look too much ahead,” says Stich. “Later this summer we’ll put all the work in front of us after this vehicle comes back with the crew and then figure out the way forward.”

In preparation for that work, Boeing and NASA want to collect as much data as possible about the systems. Boeing has already tested the thrusters while the spacecraft was docked to the space station. Boeing and NASA are working with ground simulators to test different scenarios to determine the cause of the problems and ensure the vehicle is safe.

The certification process is a “rigorous evaluation,” Hale said. “And it’s clear that these two issues need to be resolved” before NASA allows Boeing to fly a full crew of astronauts. He added that “thruster failures and helium leaks are something we have had to deal with all the time in the shuttle program. They were very common.”

Safety comes first, and the tragedy of the space shuttle Columbia, which disintegrated while returning from space in 2003, is always in the back of people’s minds, he said. “Those lessons are not forgotten,” he said.

Complicating matters is the fact that the helium and thruster problems are within Starliner’s service module, which provides the majority of the spacecraft’s engine power. Before returning to Earth, it is thrown overboard and burns up in the atmosphere. Engineers would like to diagnose the problems while the hardware is still accessible. That, Stich said, will allow them to “gain valuable insight into the system upgrades we want to make for post-certification missions.”

Because “the service module is not coming back, they have to get all the data they can out of it now,” said Mike Massimino, a former NASA astronaut and professor of mechanical engineering at Columbia University. “You’d want to stay in orbit as long as possible to get that data.”

Williams and Wilmore are also more than happy to remain in orbit, he said, especially since Williams was last in space in 2012 and Wilmore in 2015.

“More time in space is a great thing,” he said. “I would like to be above that. They both waited for that flight. Why rush through it?”