Low Earth orbit, a low superhighway that wraps around Earth’s thermosphere some 300 to 600 kilometers above our heads, is once again overloaded.

Yet no one knows how the massive increase in the number of satellites orbiting the Earth will affect the atmosphere, and thus life below. With the rush to send up more and more satellites, a new study suggests that the hole in the ozone layer, a problem scientists thought they solved decades ago, could be making a comeback.

“Until a few years ago, this wasn’t an area of research at all,” Martin Ross, an atmospheric scientist at Aerospace Corporation, said of the study, which looked at how a potential increase in man-made metal particles could eat away at space. The protective layer of the earth.

Since Sputnik, the first man-made space satellite, was launched in 1957, scientists have thought that when satellites reenter our atmosphere at the end of their lives, their evaporation has little impact. But new satellites — much more advanced, but also smaller, cheaper and more disposable than previous satellites — are having sales akin to fast fashion, said the study’s lead author, José Pedro Ferreira, a doctoral candidate in aerospace engineering at the University of Southern California .

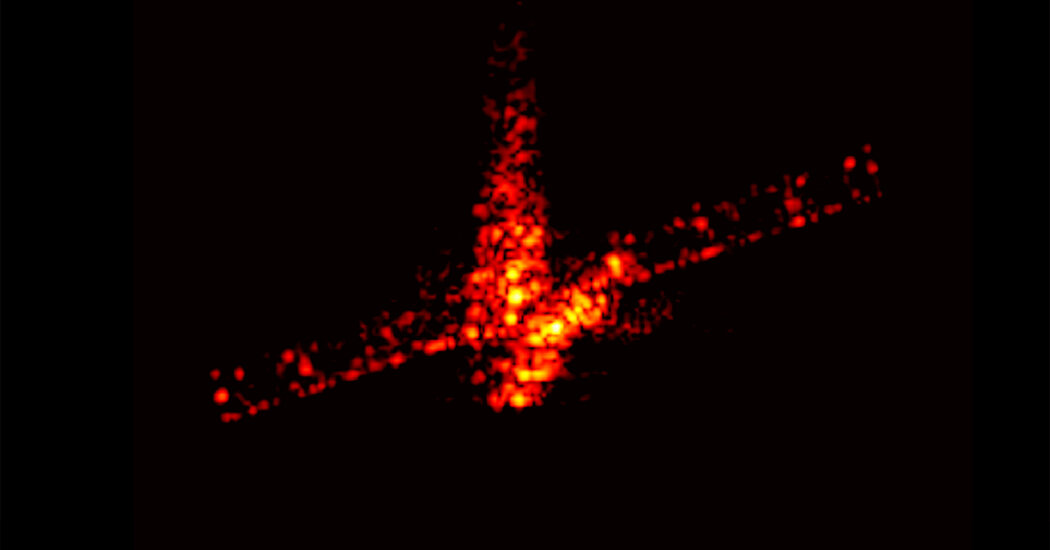

Nearly 20 percent of all satellites ever launched have reentered Earth’s atmosphere in the past five years, where they burned up in super-fast, super-hot flames.

Mr. Ferreira calculated that upon satellite return, most of a burned satellite could become alumina, a pollutant that could disrupt ozone chemistry in the stratosphere. Each satellite can generate just under 70 kilos of aluminum oxide nanoparticles.

The study, which relied on laboratory measurements and computer models, states that if the number of satellites launched results in mega-constellations of hundreds or thousands, they could create a surplus of aluminum 640 percent above natural levels, potentially leading to significant ozone development. exhaustion.

“We are just at the beginning of a major research effort, so it is too early to be sure there is a negative impact, but we are clearly starting to see the evidence,” said Mr Ferreira, whose research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, was funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

Mr Ferreira said studies like his were not anti-satellite but complemented a growing body of research into the sustainable development of space.

Daniel Cziczo, a professor of earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences at Purdue University, flies high-altitude aircraft to look at the particles left in the atmosphere by meteoroids. Last year he published a study showing that these particles coagulated with man-made metals from satellites.

He said Mr Ferreira’s study reached conclusions not supported by his own research by applying the incorrect size, composition and chemistry to the particles found in the atmosphere.

Increasing the number of launches and dismantling more satellites that are largely burning up means there will be more material in the atmosphere, said Dr. Cziczo. “It raises the question of what impact that will have, and we don’t know yet.” He said that ozone depletion and the climate impacts of satellites needed to be studied, but he felt that this article did not approach these issues correctly.

Mr Ferreira said: “models are only as good as the data you use to validate them, so we need to be careful about the level of certainty we have about environmental impacts.”

Regulators are slowly taking notice of the unanswered questions that come with increasing space hardware. In 2019, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space published long-term sustainability guidelines recommending regulating the environmental impacts of space activities on the planet. In 2022, the Federal Communications Commission, which licenses most satellites, approved 7,500 of SpaceX’s requested batch of nearly 30,000 satellites.

The Montreal Protocol, an international agreement that regulated ozone-depleting substances in 1987, was written to include gases, not particles, said Dr. Ross of Aerospace Corporation. But the regulatory body could intervene in the coming years.

“This is something that the world should really take seriously, and the Montreal Protocol is aware of this and will be studying it,” said David Fahey, co-chair of the Montreal Protocol’s Scientific Assessment Panel and director of the Chemical Sciences Laboratory at the Montreal Protocol. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The Protocol, he said, would examine the issue for their next review, due to be completed in 2026.