Deshnee Naidoo has spent her career climbing the ladder in the mining industry and finds the change in attitudes towards women “phenomenal”.

But lately, the former head of Vale Base Metals, a nickel and cobalt producer, has noticed a worrying reaction. When candidates from diverse backgrounds secure jobs, some men in the industry have taken to using the acronym DEI – diversity, equity and inclusion – in a derogatory rephrasing: “Didn’t Earn It.”

“I hear more anti-wokeism voices. The jury is still out on whether it will grow,” says 48-year-old Naidoo. “We are always taken back to how things were, rather than where they should go.”

Naidoo’s experience suggests that a transatlantic backlash against diversity initiatives – in which high-profile conservatives have criticized programs such as bias training or targeting underrepresented groups in recruitment – threatens efforts to reduce gender inequality. In mining, one of the industries furthest behind in gender equality, the risk of reversing hard-won gains is particularly high.

“Globally we’re seeing this Andrew Tate effect, where men are taking back power,” said Stacy Hope, director of advocacy group Women in Mining UK, referring to the self-described ‘misogynistic’ social media influencer. “We need to take men along on this journey to ensure they become allies.”

According to some female leaders, the belief that women are promoted based on gender, not ability, has permeated middle management and the board. Naidoo says she has been accused of being “too aggressive and pushy”. “At the executive level, despite the champions we have. . . we just look so far away from what we should look like,” she adds. “At the top, the sector still looks like it used to.”

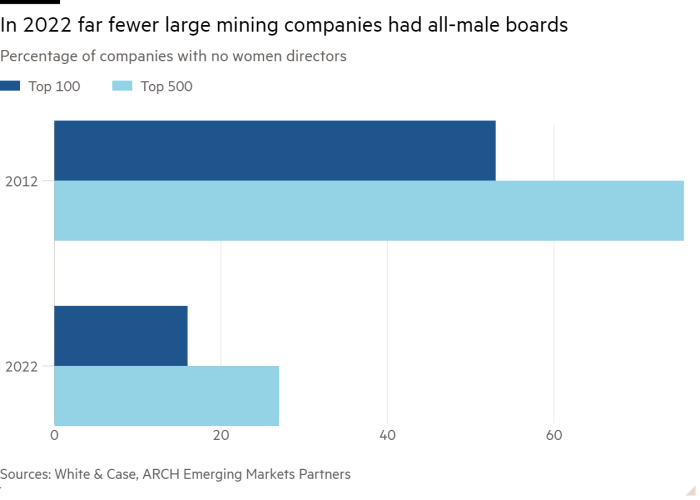

The mining industry has made remarkable progress towards gender equality over the past decade. According to law firm White & Case, the number of female directors at the 500 largest mining companies has risen from 4.9 percent in 2012 to about 18 percent in 2022.

One of the most high-profile female executives in mining is Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, the owner of an iron ore empire who has introduced pink mining trucks to raise breast cancer awareness.

But the sector is far from equal. Of the top 100 mining groups, 16 still had no women on their boards and one in four of the 500 largest companies had none, White & Case figures from 2022 showed. The diversity among ‘junior’ mining companies, which exploring and developing mines and making up the majority of the industry is still sad.

The struggle to recruit women comes as the mining sector – crucial to producing the raw materials for the international shift to clean energy – struggles to attract the most talented workforce. Young people, executives say, are increasingly more interested in becoming data engineers than miners.

A survey of mining industry leaders by consultancy McKinsey found that 71 percent said a talent shortage was preventing them from achieving production targets and strategic objectives. Another PwC survey found that two-thirds of leaders expected skills shortages to have a major impact on profitability over the next decade.

A particular challenge for extractive industries is location: mines are often located in remote places around the world. Sometimes the rural communities in which they are located have different norms than Western companies, putting female employees at risk of gender-based violence or local backlash.

To meet the interests of a new generation, the industry hopes to increasingly position itself as a technology and data-driven business that doesn’t necessarily involve being in the hole or going deep underground.

“I hate it when people regard our industry as heavy,” said Hilde Merete Aasheim, who last month ended her five-year term as CEO of Norsk Hydro, Europe’s largest aluminum producer. “That’s an old word, it’s no longer about raw muscles. It is really high-tech.”

Hope says the perception of mining as a ‘boys club’ has not done the industry any favors in attracting women. According to her, the industry must become ‘visible’ to young people, also as a sector that is essential for achieving green goals, such as limiting emissions to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“We need young people to innovate with AI and digital toolsets,” she says. “We are not doing a good job of turning this into a sector that needs young people and diverse talent to bring about that change.”

Management scandals have not helped that reputation. A 2022 report on workplace culture at British-Australian mining group Rio Tinto found that bullying and sexism were “systematic” in workplaces, a finding that CEO Jakob Stausholm called “deeply troubling.” Rio has now partially linked executive pay to gender diversity performance and will announce the results of a new review this year.

Elizabeth Broderick, the former Australian sex discrimination commissioner who led the Rio report, said discriminatory incidents in mining were “not isolated workplace grievances” but “symptoms of a tolerant culture”.

However, the situation across the sector is improving in some respects. The new amendment to Australia’s Sex Discrimination Act is a game-changer by making employers responsible for not only responding to complaints, but also taking preventative measures to create inclusive workplaces, Broderick says.

Norsk Hydro’s Aasheim is a woman who has benefited from supportive male leaders throughout her career, which started as a teenager in a bakery. “I’ve never applied for a job,” she says. “But I’ve been given many opportunities because I’ve had key leaders who saw my potential and challenged me about what I could do. . . As leaders we have to be active.”

But in light of the backlash against DEI, some believe executives should take a more proactive approach to entrenching support for women’s advancement within the workforce.

“We need to listen to men’s concerns about the changing demographics of the workforce and ensure their fears are heard and addressed,” says Broderick. “Organizations that increase women’s representation are working [not only] to change mindsets and behavior, but also to anchor everyday respect in their systems and structures.”

Additional reporting by Nic Fildes