Some truths about the universe and our experience in it seem unchangeable. The sky is up. Gravity sucks. Nothing can travel faster than light. Multicellular life needs oxygen to live. However, perhaps we should reconsider the latter.

In 2020, scientists discovered a jellyfish-like parasite that lacks a mitochondrial genome – the first multicellular organism ever to find such an absence. That means it doesn’t breathe; in fact, it lives its life completely free from oxygen dependence.

This discovery not only changes our understanding of how life can work here on Earth – it could also have implications for the search for extraterrestrial life.

Life began to evolve the ability to metabolize oxygen, that is, to breathe, more than 1.45 billion years ago. A larger archaeon engulfed a smaller bacterium, and somehow the bacterium’s new home was beneficial to both parties, and the two stayed together.

That symbiotic relationship resulted in the two organisms co-evolving, and eventually the bacteria that nested within them became organelles called mitochondria. Every cell in your body, except red blood cells, has large numbers of mitochondria, and these are essential for the breathing process.

They break down oxygen and produce a molecule called adenosine triphosphate, which multicellular organisms use to power cellular processes.

We know that there are adaptations that allow some organisms to thrive in low-oxygen or hypoxic conditions. Some unicellular organisms have evolved mitochondria-related organelles for anaerobic metabolism; but the possibility of exclusively anaerobic multicellular organisms had been the subject of scientific debate.

That was until a team of researchers led by Dayana Yahalomi of Tel Aviv University in Israel decided to take another look at a common salmon parasite called Henneguya salminicola.

(Stephen Douglas Atkinson)

It is a cnidarian, belonging to the same phylum as corals, jellyfish and anemones. Although the cysts this creates in the fish’s flesh are unsightly, the parasites are not harmful and will live together for the salmon’s entire life cycle.

Hidden within its host, the small cnidarin can survive quite hypoxic conditions. But exactly how that happens is hard to figure out without looking at the creature’s DNA – so that’s what the researchers did.

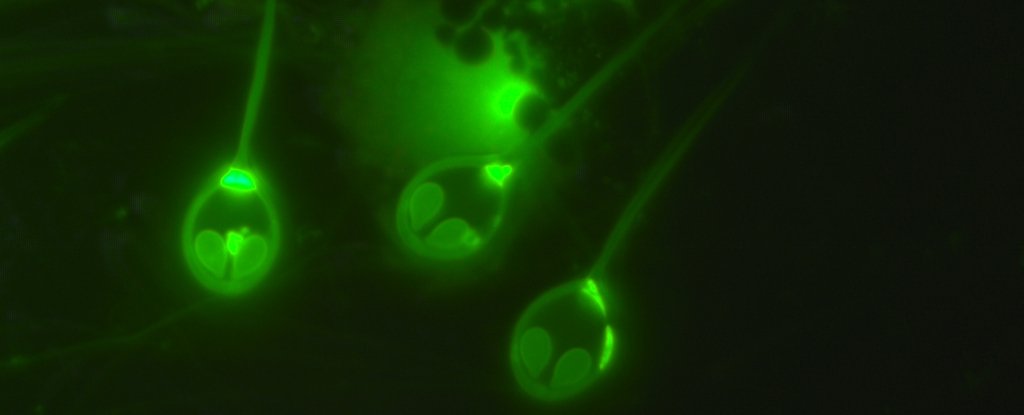

They used deep sequencing and fluorescent microscopy to study this in detail H. salminicola, and discovered that it had lost its mitochondrial genome. In addition, it also lost the ability for aerobic respiration and almost all nuclear genes involved in transcribing and replicating mitochondria.

Like the single-celled organisms, it had developed mitochondria-related organelles, but these are also unusual: they have folds in the inner membrane that you normally don’t see.

The same sequencing and microscopic methods in a closely related nettle fish parasite, Myxobolus squamaliswas used as a control and clearly showed a mitochondrial genome.

These results showed that here finally was a multicellular organism that does not need oxygen to survive.

While H. salminicola is still a mystery, the loss is quite consistent with a general trend in these creatures – one of genetic simplification. Over many, many years, they actually evolved from a free-living ancestor of jellyfish to the much simpler parasite we see today.

(Stephen Douglas Atkinson)

(Stephen Douglas Atkinson)

They have lost most of the original jellyfish genome, but – strangely – retain a complex structure that resembles jellyfish stinging cells. They do not use these to sting, but to cling to their hosts: an evolutionary adaptation of the needs of the free-living jellyfish to those of the parasite. You can see them in the image above – they’re the things that look like eyes.

The discovery could help fisheries adapt their strategies for dealing with the parasite; Although it is harmless to humans, no one wants to buy salmon covered in small weird jellyfish.

But it is also a great discovery to help us understand how life works.

“Our discovery confirms that adaptation to an anaerobic environment is not unique to unicellular eukaryotes, but has also evolved in a multicellular, parasitic animal,” the researchers explained in their paper, published in February 2020.

“Hence, H. salminicola provides an opportunity to understand the evolutionary transition from an aerobic to an exclusively anaerobic metabolism.”

The research was published in PNAS.

An earlier version of this article appeared in February 2020.