For thousands of years, philosophers have debated the purpose of language. Plato believed it was essential for thinking. Thinking “is a silent inner conversation of the soul with itself,” he wrote.

Many modern scholars have advanced similar views. Beginning in the 1960s, Noam Chomsky, a linguist at MIT, argued that we use language for reasoning and other forms of thinking. “If there is a serious shortage of language, there will also be a serious shortage of thoughts,” he wrote.

As a student, Evelina Fedorenko took Dr. Chomsky and heard him describe his theory. “I thought it was a really nice idea,” she remembers. But she was surprised at the lack of evidence. “A lot of things he said were just said as if they were facts — the truth,” she said.

Dr. Fedorenko went on to become a cognitive neuroscientist at MIT, using brain scans to study how the brain produces language. And after fifteen years, her research has led her to a surprising conclusion: we don’t need language to think.

“When you start to evaluate it, you just don’t find support for this role of language in thinking,” she said.

When Dr. Fedorenko started this work in 2009, research showed that the same brain areas needed for language were also active when people reasoned or performed arithmetic.

But Dr. Fedorenko and other researchers discovered that this overlap was a mirage. Part of the problem with the early results was that the scanners were relatively crude. Scientists made the most of their fuzzy scans by combining the results from all their volunteers, creating an overall average of brain activity.

In her own research, Dr. Fedorenko more powerful scanners and performed more tests on each volunteer. These steps allowed her and her colleagues to collect enough data from each person to create a fine-grained picture of an individual brain.

The scientists then conducted studies to pinpoint brain circuits involved in language tasks, such as retrieving words from memory and following grammar rules. In a typical experiment, volunteers read gibberish followed by real sentences. The scientists discovered certain areas of the brain that only became active when volunteers processed actual language.

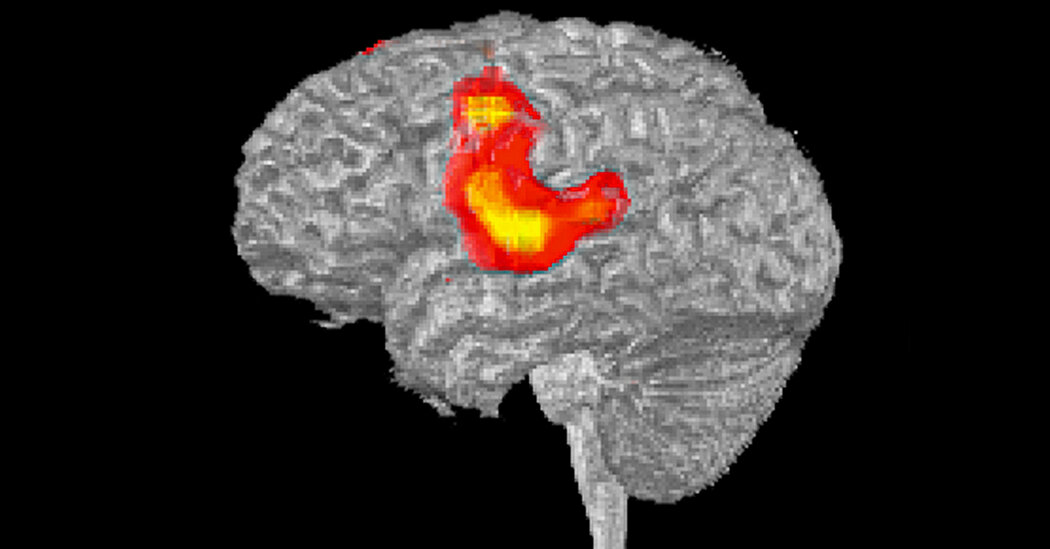

Each volunteer had a language network: a constellation of regions that become active during language tasks. “It’s very stable,” said Dr. Fedorenko. “If I scan you today, and 10 or 15 years later, it will be in the same place.”

The researchers then scanned the same people as they performed different types of thoughts, such as solving a puzzle. “Other parts of the brain are working really hard when you’re doing all these types of thinking,” she said. But the language networks remained silent. “It became clear that none of these things seem to affect language circuits,” she said.

In a paper published Wednesday in Nature, Dr. Fedorenko and her colleagues that studies of people with brain damage lead to the same conclusion.

Strokes and other forms of brain damage can wipe out the language network, leaving people with difficulty processing words and grammar, a condition known as aphasia. But scientists have found that even with aphasia, people can still do algebra and play chess. In experiments, people with aphasia can look at two numbers – for example 123 and 321 – and recognize that, using the same pattern, 456 should be followed by 654.

If language is not essential for thinking, what is language for? Communication, argue Dr. Fedorenko and her colleagues. Dr. Chomsky and other researchers have rejected that idea, pointing to the ambiguity of words and the difficulty of expressing our intuitions aloud. “The system is not well designed in many functional respects,” said Dr. Chomsky ever.

But major studies have suggested that languages are optimized to convey information clearly and efficiently.

In one study, researchers found that commonly used words are shorter, making languages easier to learn and speeding up the flow of information. In another study, researchers examining 37 languages found that grammar rules place words close together so that their combined meaning is easier to understand.

Kyle Mahowald, a linguist at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the new work, said separating thought and language could help explain why artificial intelligence systems like ChatGPT are so good at some tasks and so bad at others.

Computer scientists train these programs on large amounts of text to discover rules about how words are connected. Dr. Mahowald suspects that these programs begin to mimic the language network in the human brain, but fall short in reasoning.

“It is possible to have very fluent grammatical texts, which may or may not have a coherent underlying idea,” said Dr. Mahowald.

Dr. Fedorenko noted that many people intuitively believe that language is essential for thinking because they have an inner voice that narrates all their thoughts. But not everyone has this constant monologue. And few studies have examined the phenomenon.

“I don’t have a model of this yet,” she said. “I didn’t even do what I should have done to speculate like this.”