Officials will also investigate whether the parachute system, which Boeing had to redesign after an earlier test flight without anyone on board, ensures a safe landing in what would be the final act of Starliner’s first flight with people on board.

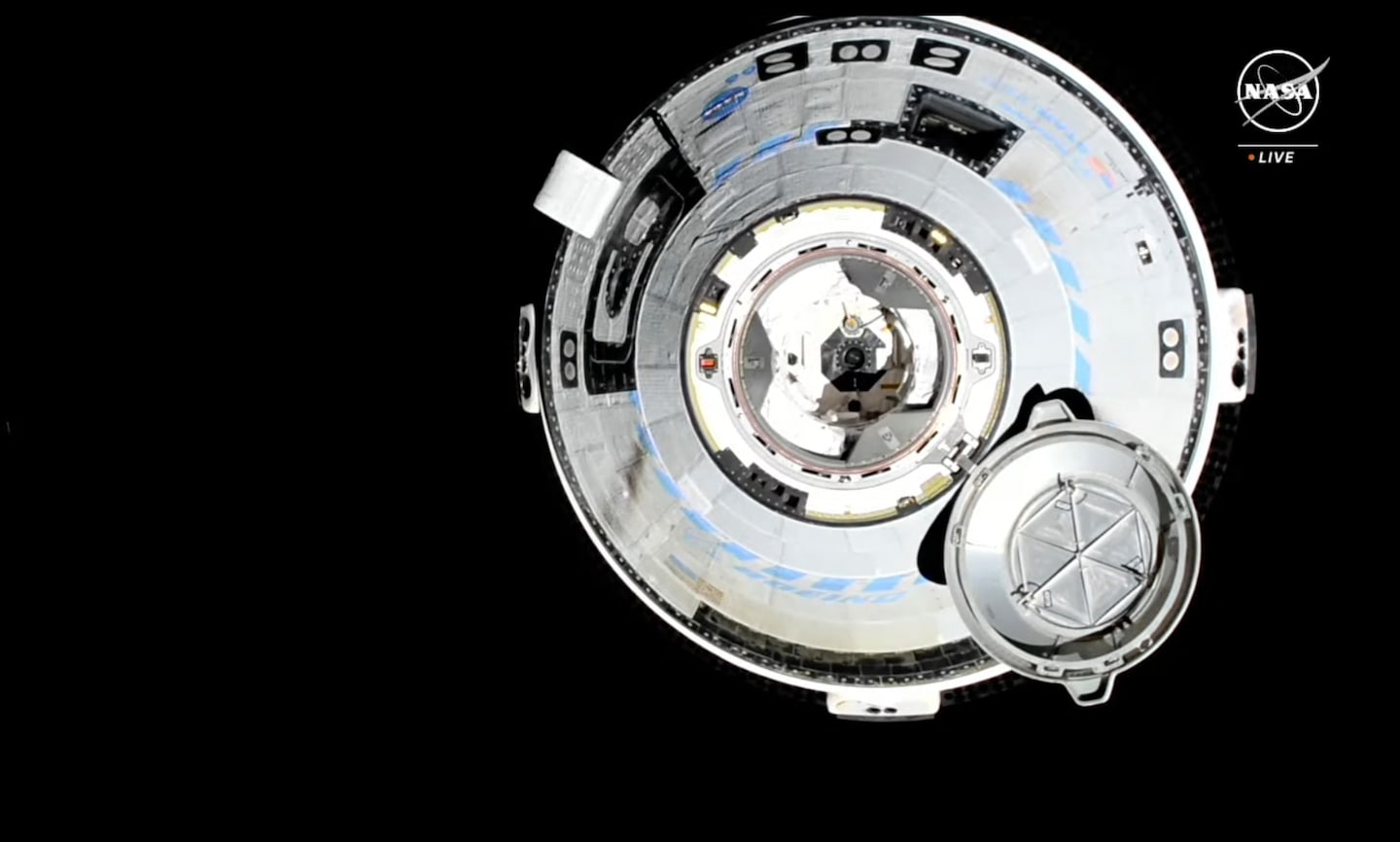

After delays caused by a defective valve on the rocket and helium leaks in the spacecraft, Starliner launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on June 5, reaching the station a day later. As Starliner approached the station, five of its thrusters, used to make minor adjustments to the trajectory, went offline, forcing Boeing to reverse the vehicle away from the station and fix the problem.

NASA and Boeing were able to bring four of the five back online and dock successfully.

The teams tested the thrusters Saturday while the spacecraft was attached to the station, and they all worked well, NASA said. They did not attempt to test the one thruster that did not come back online during the flight and will not attempt to use it during Starliner’s return flight “out of an abundance of caution,” Steve Stich, NASA’s commercial crew program manager. said during a briefing on Tuesday.

In addition to the bow thruster problems, Starliner has also suffered a series of helium leaks in its propulsion system. NASA and Boeing have discovered a new one – the fifth – since Starliner arrived on station. That leak is small and will not pose a problem for reentry, NASA said. Helium is used to pressurize the propellants through the propulsion system.

GET SAVED

Stories to keep you informed

NASA originally said Starliner would return home on June 18, but then pushed back the landing to June 22. The problems with the thruster and helium leaks are in the spacecraft’s service module, which is used to maneuver the capsule during flight. Before the capsule reenters Earth’s atmosphere, the service module is jettisoned and burned. That means engineers can’t study it after the flight, which is one reason they said they now needed more time to understand the issues.

“We’re taking our extra time, since this is a crewed vehicle, and we want to make sure we haven’t left anything unturned,” Stich said. “We also want to look at the systems and the possible interaction between the systems and make sure we haven’t missed anything before we come back. And we’re getting a lot of great data while we’re on the space station, not just for this flight, but for the next flight as well.”

NASA and Boeing believe the thrusters went offline because of the extreme heat generated while they were firing in “rapid succession” to keep the capsule on track with the space station, Stich said.

“In some cases we think the heating may have caused the propellants to evaporate a bit and we didn’t get good mixing. [of the propellants], and therefore the thrust was slightly lower,” he said. Engineers still don’t understand what’s causing the helium leaks, he said.

While on the space station, Williams and Wilmore prepared for their return and practiced using Starliner as a safe haven in the event of an emergency on the space station. They also worked with the other astronauts “by installing research equipment, maintaining laboratory hardware and helping station crew members Matt Dominick and Tracy Dyson prepare for a spacewalk,” NASA said in a statement.

Despite the problems, NASA expressed confidence in Starliner. Officials said they expected to discover problems during the mission, a test flight designed to see how Starliner operates with people on board.

“We’ve always said this as a test flight and we’re going to learn some things,” said Mark Nappi, a Boeing vice president who oversees the Starliner program. “So here we are. We learned that our helium system is not performing as designed, even though it is controllable. … So we have to figure that out.”

Once the mission is complete, NASA would certify Starliner for regular rotational flights with a full contingent of four astronauts to the space station. SpaceX, the other participant in NASA’s commercial crew program, which outsourced human spaceflight to the private sector after the space shuttle was retired, has been flying astronauts for NASA since 2020.

Given the problems Starliner encountered during this test flight, it is not clear when Boeing, which was awarded a $4.2 billion NASA contract in 2014, will fly its first regular crew rotation mission.

“We need to address the helium leaks,” Stich said. “We’re not going to fly another mission like this with the helium leaks.” The teams also need to figure out what “causes the thrusters to have low thrust,” he added. “So we still have some of that work to do after this flight.”