Shrouded in a dense cloud of gas and dust, a young star in the constellation Ophiuchus that astronomers have studied for decades turns out to be a duo. It also appears that both members of the pair are surrounded by a disk of material within which planets have just begun to merge.

The twin stars, which are located about 400 light years by Soil in the WL 20 group, are less than a million years old and appear to have displaced the wavy orange clouds within which they formed, indicating that their birth processes are nearing completion. That means astronomers can observe the stars as they transition to maturity.

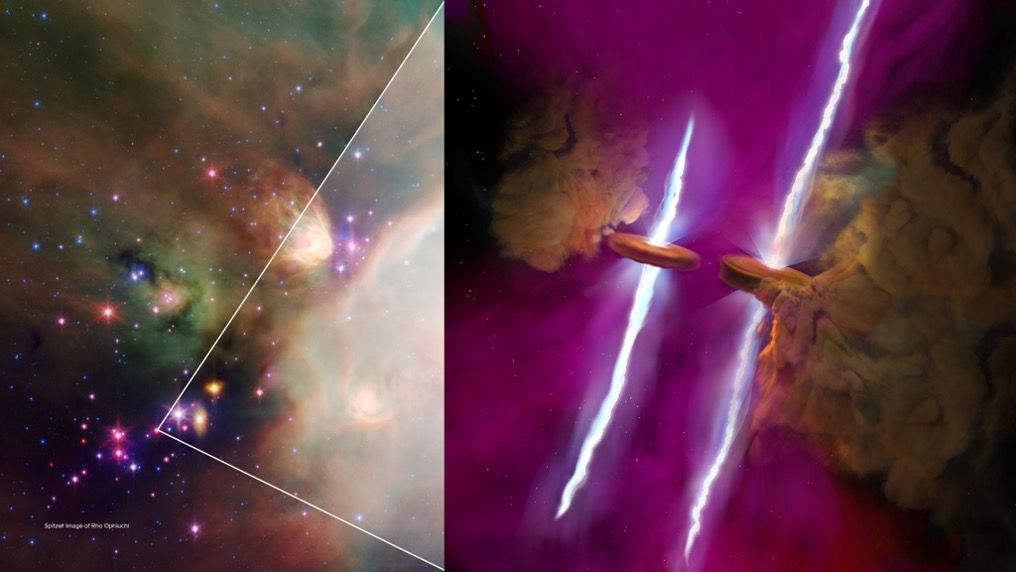

For decades, telescope observations have shown the WL 20 group located in a huge molecular cloud called Rho Ophiuchi, houses three stars, spread out like points of a triangle. Although they were born in the same bag of gas and dust, two stars were about two million years old. The third star – the faintest of the group at the southern tip of the triangle – appeared younger than a million years old.

“How can this be?” Mary Barsony, an independent astronomer who led the discovery, said this Wednesday (June 12) while presenting the discovery at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Wisconsin. Many astronomers, including Barsony, have studied the triplets in WL 20 and their cosmic home Rho Ophiuchi for decades. “We thought we knew it pretty well,” she said in one rack provided by NASA.

Related: ‘Supernova discovery machine’ James Webb Space Telescope finds the most distant star explosion ever recorded

But then the James Webb Space Telescope While observing the region, its powerful Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) discovered that the third star, named WL 20S, was in fact a twin itself – each member of the pair with matching jets streaming in room of its north and south poles. Additional observations by ALMA (short for Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array), a large network of 60 radio antennas in Chile that work like a giant telescope, revealed that each of the twin stars was also surrounded by a disk of gas and dust. If one of the twin stars were to replace our sun, its disk would extend further Saturn‘s job, Barsony said.

“We were absolutely stunned when we first saw these images,” she told reporters at a news conference. Without MIRI, astronomers would not have known about the twin star or the jets, she added. “It’s like having brand new eyes.”

Astronomers do not fully understand how multiple star systems, such as the four-star one in WL 20, form. Future observations of the quadruplets could therefore shed more light on the underlying processes.

“It’s amazing that this region still has so much to teach us about the life cycle of stars,” said co-author Mike Ressler, project scientist for MIRI at NASA. Jet propulsion laboratory and has been studying the WL 20 group for almost 30 years.

When Ressler got some observing time at JWST, he chose to point the telescope at WL 20, which was in the opposite part of the sky from his other targets.

“I thought, why don’t we sneak it in? I’ll never get another chance, even if it doesn’t quite fit in with the others,” Ressler said. “We had a very fortunate accident with what we found; the results are amazing.”