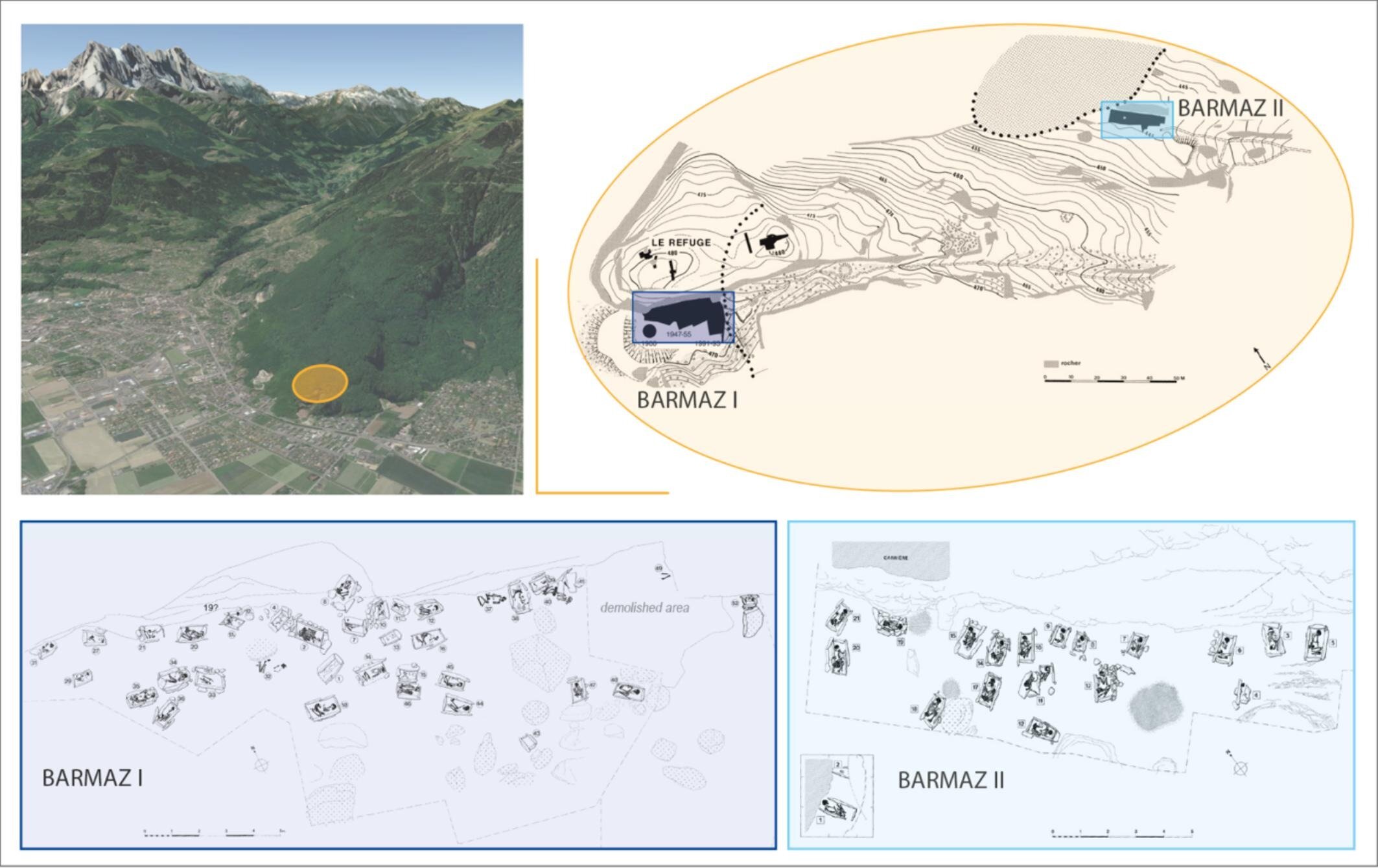

In orange the location of the Barmaz site, looking south. It is located on the plain, at the foot of the Chablais massif, which rises to an altitude of 2,500 meters. The site is divided into two contemporary cemeteries called Barmaz I (dark blue) and Barmaz II (light blue) (Honegger and Desideri 2003, modified). Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104585

Using isotope geochemistry, a team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has discovered new information about the Barmaz necropolis in Valais (Switzerland): 14% of the people buried at this site 6,000 years ago were not local residents. Furthermore, the study suggests that this Middle Neolithic agropastoral society – one of the oldest known in the western part of Switzerland – was relatively egalitarian.

The isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in the bones show that all community members, including people from elsewhere, had access to the same food sources. These results are published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: reports.

The Neolithic marked the beginning of livestock farming and agriculture. In Switzerland this period extends between 5500 and 2200 BC. The first agropastoral communities gradually transitioned from a predatory economy – in which hunting and gathering provided the nutrients essential for survival – to a production economy.

This radically changed the dietary habits and functioning dynamics of Neolithic populations. The bones and teeth of individuals contain chemical traces that scientists can now detect and interpret.

The aim of the study carried out by Déborah Rosselet-Christ, a doctoral student at the Laboratory of Archeology of Africa and Anthropology of the UNIGE Faculty of Science, is to apply isotope analysis to human remains from the Neolithic period to learn more about their diet and mobility.

The levels of certain isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur and strontium depend on the environment in which each individual lives and eats. Isotopes are atoms that have the same number of electrons and protons, but a different number of neutrons. This very precise and delicate technique is applied for the first time to alpine agropastoral populations from the Middle Neolithic in the western part of Switzerland.

Mobility according to the second molar

The Barmaz site at Collombey-Muraz in the Chablais region of Valais, excavated in the 1950s and 1990s, is one of the oldest remains of agropastoral societies in the western part of Switzerland where human remains have been preserved. It consists of two necropolises containing the bones of approximately seventy individuals. For her master’s degree, Déborah Rosselet-Christ, the first author of the study, selected 49 of them (as many women as men) from whom she systematically took collagen samples from certain bones, as well as fragments of enamel from their second molars.

“The second molar is a tooth whose crown forms between the ages of three and eight,” the researcher explains.

“Once formed, tooth enamel is not renewed for the rest of its life. Its chemical composition therefore reflects the environment in which the owner lived during childhood. Strontium (Sr) is a good marker of mobility. The ratio of abundance between two of its isotopes – that is, their proportion – varies greatly depending on the age of the surrounding rocks. These chemical elements enter the glaze through the food chain, leaving an indelible signature specific to each environment.

Analysis of the strontium isotope ratios in the 49 individuals from Barmaz reveals a high degree of homogeneity in most of them and clearly different values in only 14% of the samples, indicating a different origin.

“The technique makes it possible to determine that these are individuals who did not live the first years of their lives in the place where they are buried, but it is more difficult to determine where they come from,” says Jocelyne Desideri, senior lecturer at the Laboratory of Archeology of Africa and Anthropology of the UNIGE Faculty of Science, last author of the article.

“Our results show that people were on the move at that time. This is not surprising, as several studies have highlighted the same phenomenon in other places and at other times during the Neolithic period.”

Diet included in collagen

Collagen is used to determine the ratios of isotopes of carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N) and sulfur (δ34S). Each measurement provides information on specific aspects of the diet, such as the categories of plants according to the type of photosynthesis they use, the amount of animal protein or the intake of aquatic animals.

Because bones are constantly being renewed, the results only cover the last few years of a person’s life. That said, the scientists were able to conclude that these former inhabitants of the Barmaz region followed a diet based on terrestrial (rather than aquatic) resources, with a very high consumption of animal protein.

“What is more interesting is that we did not measure any differences between men and women,” notes Déborah Rosselet-Christ.

“Not even between locals and non-locals. These results therefore suggest equal access to food resources among different members of the group, regardless of their origin or gender. However, this is not always the case. For example, there are nutritional differences between the sexes in Neolithic populations in the south of France.”

A clearer picture of agropastoral societies

However, the scientists were able to show that non-local people were buried in only one of the necropolises (Barmaz I) and that higher levels of the nitrogen isotope were measured in the other (Barmaz II). Since the two necropolises were contemporaneous (and only 150 meters apart), this last observation raises the question of whether there was a difference in social status between the two groups of deceased.

“Our isotope measurements are an interesting addition to other approaches used in archaeology,” says Jocelyne Desideri. “They help clarify the picture we are trying to paint of the life of these early agropastoral societies in the Alps, the relationships between individuals and their mobility.”

Déborah Rosselet-Christ is currently pursuing this work as part of her doctoral dissertation, co-directed by Jocelyne Desideri and Massimo Chiaradia (senior lecturer, Department of Earth Sciences).

She works with a multidisciplinary team specializing in genetics, paleopathology, dental calculus and morphology and broadens her field to include other sites in Valais and the Val d’Aosta in Italy, covering a wider Neolithic period and using different isotopes, such as neodymium, which are potentially interesting in a prehistoric archaeological context.

More information:

Déborah Rosselet-Christ et al, First Swiss agropastoral societies in the Alps: contribution of isotope analysis to the study of their diet and mobility, Journal of Archaeological Science: reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104585

Provided by the University of Geneva

Quote: Isotope study suggests men and women had equal access to resources 6,000 years ago (2024, June 13), retrieved June 14, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-06-isotope-men-women-equal- access. html

This document is copyrighted. Except for fair dealing purposes for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.