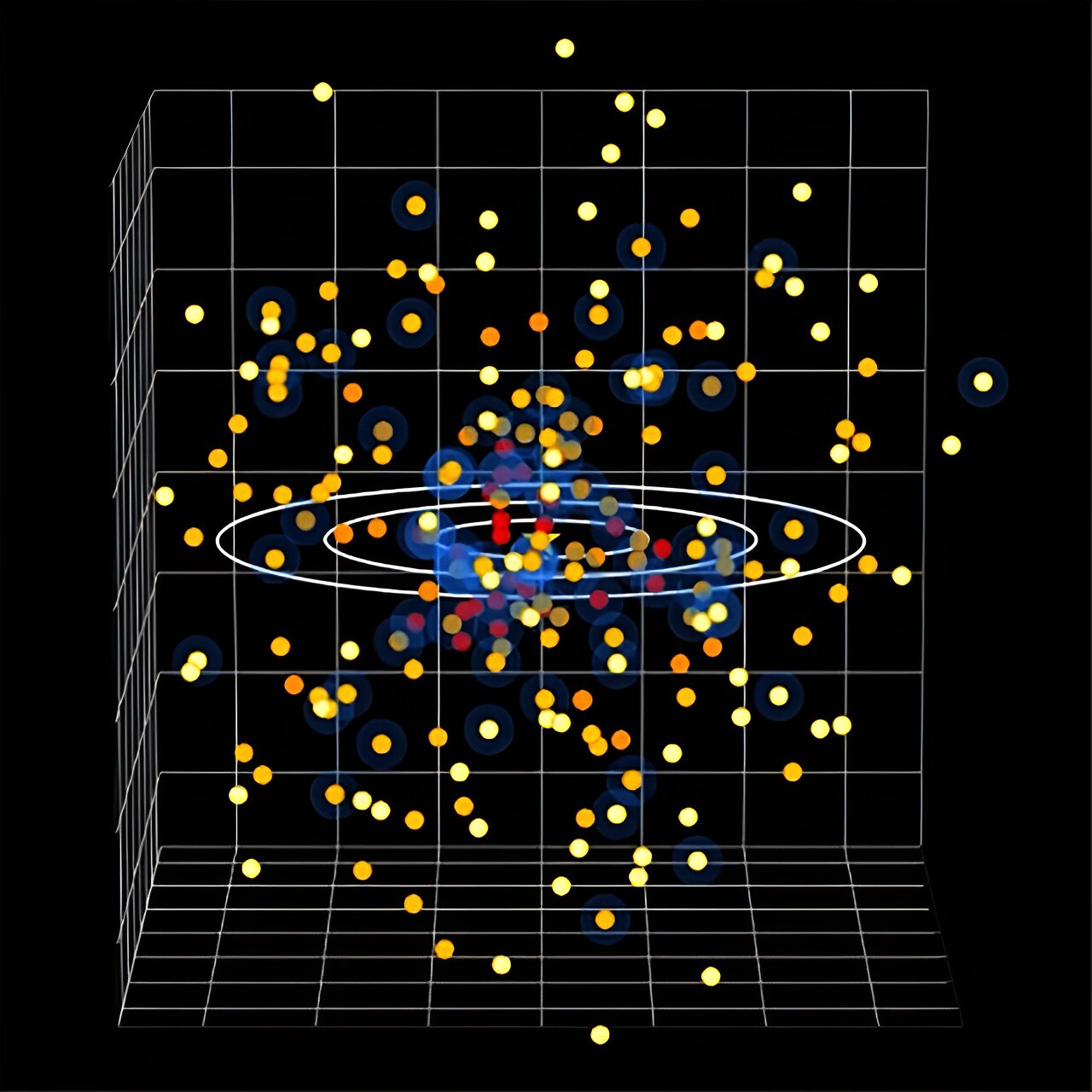

This image shows a three-dimensional map of stars near the Sun. These stars are so close that they could be prime targets for direct searches for planets using future telescopes. The blue halos represent stars observed with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton. The yellow star in the center of this diagram represents the position of the sun. The concentric rings show distances of 5, 10 and 15 parsecs (one parsec corresponds to about 3.2 light years). Credit: Cal Poly Pomona/B. Binder; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

× close to

This image shows a three-dimensional map of stars near the Sun. These stars are so close that they could be prime targets for direct searches for planets using future telescopes. The blue halos represent stars observed with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s XMM-Newton. The yellow star in the center of this diagram represents the position of the sun. The concentric rings show distances of 5, 10 and 15 parsecs (one parsec corresponds to about 3.2 light years). Credit: Cal Poly Pomona/B. Binder; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

Using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA’s (European Space Agency’s) destroy. This type of research will help guide observations with the next generation of telescopes that aim to capture the first images of planets like Earth.

A team of researchers has examined stars so close to Earth that future telescopes could capture images of planets in their so-called habitable zones, defined as orbits where the planets can have liquid water on their surfaces. Their results were presented at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin.

All images of planets are individual points of light and do not directly show surface features such as clouds, continents and oceans. However, their spectra – the amount of light at different wavelengths – will reveal information about the composition of the planets’ surfaces and atmospheres.

There are several factors that influence what might make a planet suitable for life as we know it. One of those factors is the amount of harmful X-rays and ultraviolet light the planet receives from its parent star, which can damage or even strip away the planet’s atmosphere.

“Without characterizing the X-ray emissions from its host star, we would be missing a key element about whether a planet is truly habitable or not,” said Breanna Binder of California State Polytechnic University at Pomona, who led the study. “We need to look at what kind of X-rays these planets receive.”

Binder and her colleagues started with a list of stars close enough to Earth for which future ground- and space-based telescopes could obtain images of planets within their habitable zones. These future telescopes include the Habitable Worlds Observatory and extremely large ground-based telescopes.

Based on X-ray observations of some of these stars using data from Chandra and XMM-Newton, Binder’s team investigated which stars could host planets with hospitable conditions for life to emerge and flourish.

The team studied how bright the stars are in X-rays, how energetic the X-rays are, and how much and how quickly the X-rays change, for example as a result of solar flares. Brighter and more energetic X-rays can do more damage to the atmospheres of orbiting planets.

“We identified stars whose X-ray environments in the habitable zone are similar to or even milder than those in which Earth evolved,” said study co-author Sarah Peacock from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “Such conditions can play a key role in maintaining a rich atmosphere like that on Earth.”

The researchers used data from archives of nearly ten days of Chandra observations and about 26 days of XMM observations to examine the X-ray behavior of 57 nearby stars, some of which have known planets. Most of these are giant planets such as Jupiter, Saturn or Neptune, while only a handful of planets or planet candidates may be less than about twice as massive as Earth.

There are likely many more planets orbiting stars, especially planets similar in size to Earth, that have gone unnoticed until now. Transit studies, which look for small dips in light when planets pass in front of their stars from our perspective, miss many planets because special geometry is needed to spot them. This means that the chance of detecting transiting planets in a small number of stars is small; only one exoplanet in the sample was picked up by transits.

The other major technique for detecting planets is through the detection of star wobble caused by the orbiting planets, and this technique is especially sensitive for finding giant planets that are relatively close to their host stars .

“We don’t know how many Earth-like planets will be discovered in images with the next generation of telescopes, but we do know that time to observe them will be precious and extremely difficult to obtain,” said co-author Edward Schwieterman of the University of California at Riverside. “This X-ray data will help refine and prioritize the target list and could allow the first image of an Earth-like planet to be obtained more quickly.”