Mars could encounter more than twice as many encounters with potentially dangerous asteroids as Earth, according to a new study. This could jeopardize exploration missions to the Red Planet, but also provide insight into how the inner solar system formed.

Asteroids pose the greatest threat to our planet from space; for example, the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor generated shockwaves that injured more than 1,000 people and caused more than $33 million in infrastructure damage.

Astronomers and civilian asteroid hunters have discovered about 33,000 similar space rocks zooming close to Earth as they orbit the sun. Some of it is enormous – more than 140 meters in diameter – and swirls along paths that approach Earth’s orbit at distances of less than 0.05 astronomical unit (AU). (For reference, 1 AU is about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers – the average distance between Earth and the Sun.) Tracking such potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs) is an important part of planetary defense programs.

Neighboring Mars should have it even worse, because it’s right next to the main belt: a planet-free patch of rocky debris between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. But it is not clear exactly how many asteroids are swinging past Mars. This could be a problem, co-author Yufan Fane Zhou, a doctoral student in astronomy at Nanjing University in China, told LiveScience in an email; Mars is home to many current missions and may one day be home to human colonies.

Related: The gigantic impact of the Martian asteroid creates a huge field of destruction with 2 billion craters

To test whether people on the Red Planet are at greater risk of potentially devastating consequences, Zhou and colleagues at Nanjing University analyzed how many asteroids come close to Mars. They called these space rocks “CAPHAs,” an acronym for “close approach to potentially hazardous asteroids.”

To determine Mars’s number of CAPHAs, the team used computer models to simulate the motion of all eight planets and about 11,000 randomly chosen asteroids over a period of 100 million years. All these asteroids started in the main belt. The team then looked at each asteroid’s proximity to six known holes — asteroid-poor zones within the main belt where runaway rocks could slip — and classified about 10,000 asteroids as “near-hole.”

During the simulations, the researchers allowed the asteroids near the gap to drift away or towards the sun. This drift is created by the Yarkovsky effect, a force generated when the sunlit surfaces of asteroids re-radiate the energy they receive, acting like mini thrusters. Simulating this drift is critical because it causes the asteroids near the rift to swing into the gaps over the millennia. Once there, periodic gravitational pulls from Jupiter or Saturn distort the paths of these asteroids, putting them on possible collision courses with the inner planets.

The simulations showed that about 52 large asteroids wander dangerously close to Mars each Earth year – about 2.6 times more than the 20 or so that approach Earth each year. Although these asteroids pass closer to Mars than Earth’s CAPHAs do to our planet, they also travel more slowly.

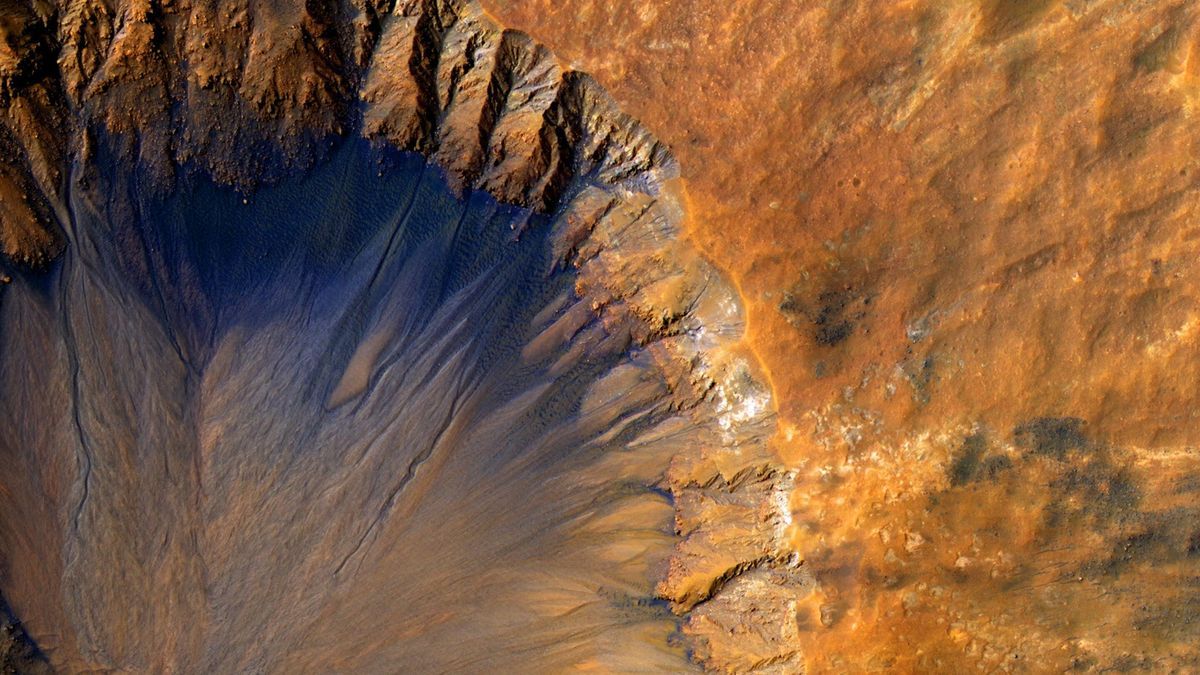

NASA missions may have already witnessed the effects of some of these asteroids impacting Mars; a meteorite impact on December 24, 2021 caused a magnitude 4 marsquake that was picked up by NASA’s Mars InSight lander.

Although Zhou was ambivalent about whether objects near Mars could affect current missions, he noted that in the future, “as human visits to Mars become more frequent, the threat posed by Mars CAPHAs will become increasingly serious will be taken.”

Yet the Mars CAPHAs can also be informative for astronomers. “Asteroids around Mars can also deepen our understanding of the Martian environment, the interactions between asteroids and planets, and the evolutionary history of the inner Solar System,” said Zhou. In fact, Zhou and colleagues suggest that at least two of these CAPHAs will even be visible from Earth in early 2025, when Mars will align with Earth while orbiting on the same side of the Sun.

The research was published online May 9 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters.

Original published at Live Science.