Everything in society can feel like it’s focused on optimization – whether it’s standardized testing or artificial intelligence algorithms. We are taught to know what outcome you want to achieve, and to find the path to get there.

Kenneth Stanley, a former OpenAI researcher and co-founder of a new social media platform called Maven, has been preaching for years that this way of thinking is counterproductive, if not downright harmful. Instead of prioritizing goals, Stanley says we should prioritize serendipity.

“Sometimes, to find the stepping stones that lead to the things we care about, we have to step off the path of purpose and onto the path of the interesting,” Stanley told TechCrunch in a video interview. “Serendipity is the opposite of finding something through goals.”

The idea of seeking novelty itself started as an algorithmic concept that Stanley in his studies called open-endedness, a subfield of AI research into systems that “continue to produce interesting things forever.”

“Open-ended systems are like artificially creative systems,” Stanley said, noting that humans, evolution and civilization are all also open-ended systems that keep building on themselves in unexpected ways.

This algorithmic insight turned into a philosophy of life for Stanley. He even wrote a book about it in 2015 with his former PhD student named Joel Lehman Why greatness can’t be planned. The concept caught on, making Stanley an international focal point for the cheeky idea that you can actually do things just because they’re interesting, rather than because you have to achieve a specific goal.

But in 2022, while leading an open-ended team at OpenAI, Stanley said he “boiled over with dissatisfaction” and “had an epiphany” in which he decided to stop talking about bringing openness to a broader audience and to do something about it instead. .

What if, he wondered, he created a “serendipity network,” a system set up to increase the likelihood of serendipity, for other people to enjoy?

So he quit his job and started founding Maven, a social network built around an open-ended AI algorithm that evolves to search for novelty. When signing up, users select a range of topics to follow – from neuroscience to parenting – and the algorithm shows them messages that match their interests. There are no likes, upvotes, retweets, or followers, and no way to amplify the content for the masses.

Instead, when a user posts something, the algorithm automatically reads the content and tags it with relevant interests so that it appears on those pages. Users can turn up the serendipity slider to explore beyond their stated interests, and the algorithm running the platform connects users with related interests. So, for example, if you’re following conversations about city planning, Maven can also suggest conversations about public transportation.

And while there’s no way to follow people on the platform, you can see and connect with other people who are following topics you’re interested in.

In many ways, Maven feels like an antidote to today’s social media, where the “objective paradox is on full display” as people fall over themselves to create sensational content that will garner more attention and popularity.

“The echo chambers and the toxicity, the reinforcement of narcissism and the personal branding have gone completely out of control, so that people are losing their souls and becoming brands,” Stanley said.

The addictive properties of social media, its damage to the mental health of adolescents and adults, and its ability to polarize countries are well documented. These, Stanley says, are the unintended consequences of ambitious goals, the result of making popularity the measure of quality.

“And then you get all these other things, because once you’re popular, you have perverse incentives,” he said.

Stanley noted that Maven users can flag inappropriate content or misinformation when it pops up, and that the AI actively checks for highly inflammatory, offensive “or worse” content. He said Maven can’t fix the nasties in human nature, but by eliminating the incentives behind sharing such content, Stanley hopes it can change the “overall dynamic of how people behave.”

Some social media companies have tried to combat such incentives in the past. The OG behind distributing casual content was StumbleUpon, a browser extension and app created by entrepreneur Garrett Camp years before he co-founded Uber. Instagram then tried hiding likes in 2019 to curb comparisons and hurt feelings that come with attaching popularity to content. X, formerly Twitter, is preparing to make likes private too, but for less healthy reasons. In a very Elon Musk-inspired line of thinking, the goal of

Maven is less interested in connecting users with the audience, and more focused on connecting them with what’s interesting.

The problem of monetization

Stanley and his co-founders – Blas Moros and Jimmy Secretan – launched Maven at the end of January. The platform debuted publicly in May alongside a Wired feature that, according to Stanley, gave Maven a top trending spot on Product Hunt and attracted thousands of signups.

Those are still small numbers compared to other newcomers to the social media space. Launched in 2021, Bluesky has had 5.6 million signups. As of January 2024, Mastodon had 1.8 million active users. Farcaster, a new crypto-based social protocol that just raised $150 million, has racked up around 350,000 signups. All of these new networks will need to grow significantly if they want to be considered successful.

It’s still an open question whether Maven will be able to grow its user base at all without the highly toxic features that we love to hate but nevertheless drag us back into the cesspool that is social media.

Maven raised $2 million in a round led by Twitter co-founder Ev Williams in 2023, Stanley told TechCrunch. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman also participated in the round. Stanley said Williams and Altman invested because, like many of us who have been endeared by Maven’s almost too-kind-for-this-world ethos, they think the world and the Internet need something like this.

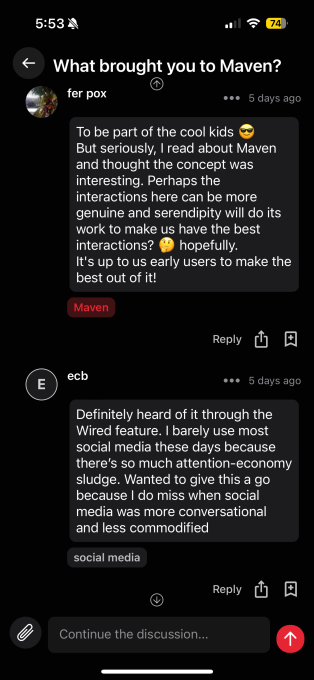

And indeed, Maven’s idealistic hope to connect people with interesting ideas is reminiscent of the early 2000s, when the Internet was a place of connection and discovery. The feelings of early users on the platform are overwhelmingly positive and optimistic, as many came to the platform for real and casual interactions and the promised freedom from toxicity.

But will idealism be enough to attract more institutional investors later if Maven wants to grow?

“I think the challenge we face is that it’s going to be an increasingly difficult way to raise money going forward,” Stanley said, noting that investors won’t throw away millions unless there’s a clear path to returns get a return on their investment.

“I just need to find the right investors and quickly come up with a sustainable business model,” he continued, musing on the idea of a subscription model that could allow Maven to keep its ideology intact.

Of course, there are other ways Maven can generate revenue. Advertising is one path, but one that is less appealing to Stanley because it is tied to virality and sensationalism.

Eventually, Maven could also sell its data to companies like OpenAI, which train their algorithms on large amounts of data. OpenAI signed a deal with Reddit earlier this month to train its AI on the social media company’s data. And Maven’s value proposition from an AI perspective isn’t even just the content on the platform – it’s the open-ended algorithm that runs it.

Stanley told TechCrunch that he believes openness is essential for artificial general intelligence (AGI), a type of AI that aims to match or surpass human capabilities for a range of cognitive tasks. Open-endedness is “such a salient aspect of being intelligent,” Stanley said. “It’s like this creative and also curiosity-driven aspect of being human.”

“The data is interesting from an AI perspective because it is data about what is interesting,” says Stanley, noting that current AI models lack the intuitive understanding of what is interesting and what is not, and how that fits into the may change over time. While the data has potential value for AI, Stanley says Maven does not have a deal with any company to grant access to that data.

And while he said he hasn’t ruled out that possibility in the future, he would think very carefully about the consequences of sharing such data.

“That’s not the point for me,” he said, noting that he’s not convinced it would be a good thing if neural networks were completely open-ended, because that would make all of humans’ creative efforts completely pointless can make.

“I really wanted to create this global, serendipitous community,” he said. “It’s not like I have a side plan that we’re going to use Maven to create open-ended AI or something like that. I just wanted to create something for people because I got the feeling that everyone will talk to chatbots more and more and that we will be less and less connected to other people. And I have contributed to that as an AI researcher.”

“Something about this idea of a serendipity network made me feel morally better, like I could actually contribute to people being more connected, not less.”