The image of an atom, with electrons swarming around a central nucleus bursting with protons and neutrons, is as iconic in our perception of science as the DNA helix or the rings of Saturn. But no matter how far we scratch the surface of these basic scientific principles, we can go deeper, focus the microscope further, and discover even more forces that rule our world.

In his new book “CHARGE: Why does gravity rule?“, theoretical physicist Frank Close examines the fundamental forces that govern our world, asking questions along the way that attempt to explain how the delicate balance of positive and negative charges paved the way for gravity to shape our universe.

In it he explains how magnetism, the most tangible of fundamental forces, was discovered, where it came from and how it got its name.

The power within

Magnetism is a manifestation of electricity, and vice versa. Electricity and magnetism were instilled in our environment from the beginning. Five billion years ago, when the newborn Earth was a hot plasma of swirling electric currents, these currents created magnetic fields. As the magma cooled and formed what is now the world’s solid outer crust, magnetism was locked in minerals containing iron, such as magnetite.

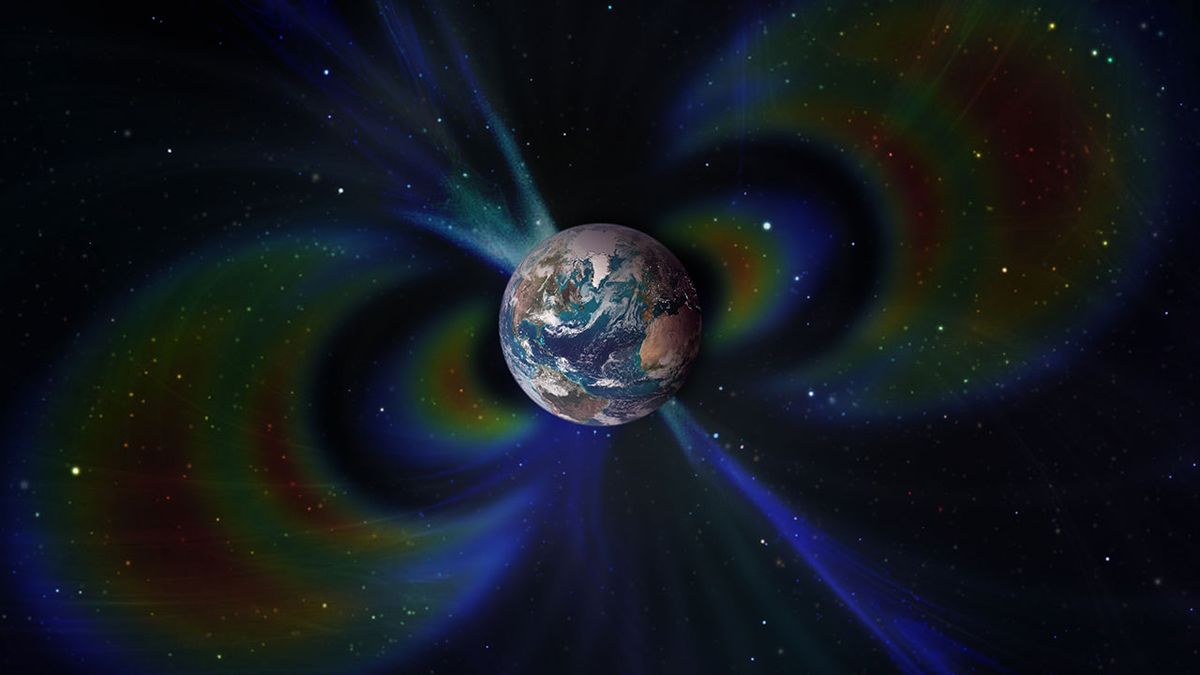

Today the The liquid core of the Earth is still a terpsichorean frenzy of electric currents, generating a magnetic field. This extends into the atmosphere and far beyond, invisible to our normal senses. But by spreading from its source in the molten core to the sky above, it first penetrates the Earth’s crust. This is where it leaves a tangible impression, proof that there exists a force more powerful than gravity and one that has a very far-reaching influence.

Way back in the earliest Precambrian, four billion years ago, as the surface cooled, atomic elements piled up in the Earth’s layers. The most stable of these, iron, is one of the most abundant elements in the crust today. Igneous rocks formed from volcanic lava. These rocks have the property that, in the presence of a magnetic field, their iron atoms behave like showpieces while becoming magnetic themselves. This is exploited in popular demonstrations where the magnetic field of a bar magnet can be made visible.

Small pieces of iron are first spread on the surface of a table and then a magnet is carefully placed between them. The magnetic field induces magnetism in the iron filings, creating thousands of miniature magnets. Each of these properly orients itself in the magnetic field and reveals how the direction of the magnetic force varies from place to place.

Related: Why do magnets have a north and a south pole?

The bar magnet is a simple model that illustrates what happens to the magnetic Earth itself. The Earth’s magnetic north and south poles are analogous to those of the bar magnet, our planet’s magnetic field that extends far into space. There are no iron filings in space, but there are large amounts of iron ore in the hills, cliffs and mountains of Earth. In some places these magnetic clusters happen to be quite extensive, such as on the island of Elba and Mount Ida in Asia Minor, where large outcrops preserve the magnetic imprint in rocks historically known as lodestone and now called magnetite.

There are legends about how thousands of years ago in ancient Greece, a shepherd, wearing leather shoes held in place by iron nails, literally stumbled upon magnetite when the powerful magnetism grabbed hold of the nails in his shoes. Whether or not a shepherd named Magnes discovered the rock of the same name, and if so, whether it was in Magnesia, north of Athens, or on Mount Ida in Asia Minor, or even another Mount Ida in Crete, it it is very likely that such experiences, if less dramatic than in the story, would have happened on several occasions.

Certainly, the power of magnetism would have been evident since the Iron Age. Lightning is a flash of electric current that generates intense magnetic fields and magnetizes ferrous rocks. Smelting to recover the pure iron metal from these sources would have revealed their magnetic attraction. So the phenomenon has probably been known for about 3,000 years. Like the discovery of fire, that of magnetism probably arose independently in several places, all inspired by the natural magnetization of iron in rocks.

Because magnetic rocks are ubiquitous. By the sixteenth century, travelers noted the best examples, from eastern India and the Chinese coast: ‘Very massive and heavy, [the stone] will draw or lift the just weight of itself in iron or steel” [Robert Norman, The Newe Attractive, 1581]. As knowledge of the phenomenon spread from Greek myth to Latin and then to English, the names changed to ‘Magnes rock’ or ‘magnet’.

© [Oxford University Press]

Excerpt from CHARGE: Why Does Gravity Rule? by Frank Close, published by Oxford University Press, available in hardback and eBook formats