About 1,000 light-years from Earth lies a cosmic structure known as IRAS 23077+6707 (IRAS 23077), which resembles a giant butterfly.

Ciprian T. Berghea, an astronomer at the US Naval Observatory, originally observed the structure in 2016 using the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS). To the surprise of many, the structure has remained unchanged for years, leading some to wonder what IRAS 2307 could be.

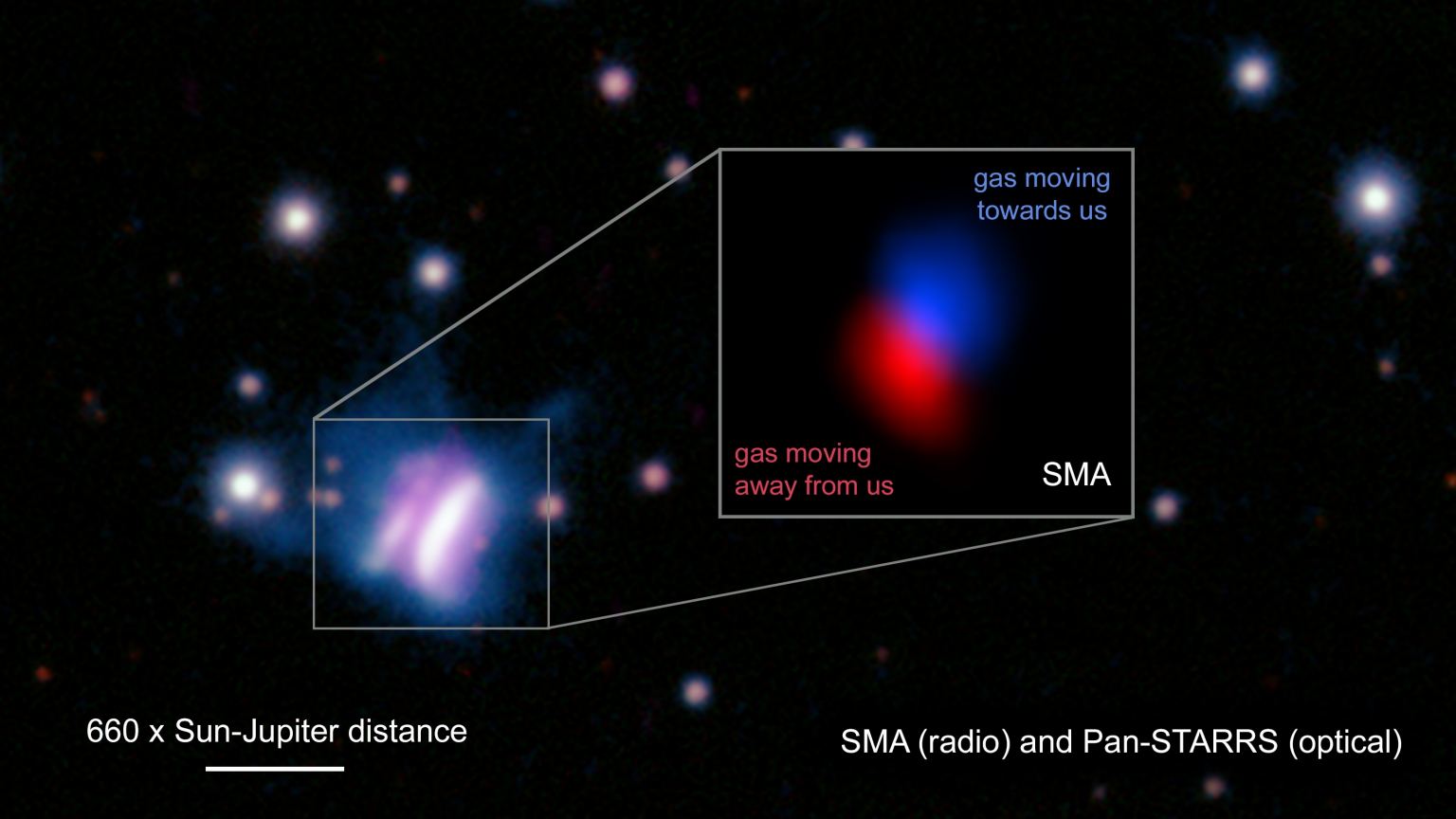

Recently, two international teams of astronomers made follow-up observations using the Submillimeter Array at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) in Hawaii to better understand IRAS 2307.

In a series of papers detailing their findings, the teams revealed that IRAS 23077 is actually a young star surrounded by a massive protoplanetary debris disk, the largest ever observed. This discovery provides new insight into planet formation and the environments in which it occurs.

The first paper, led by Berghea, reports the discovery that IRAS 23077 is a young star at the center of what appeared to be a massive planet-forming disk. In the second paper, led by CfA postdoc Kristina Monsch, the researchers confirm the discovery of this protoplanetary disk using data from Pan-STARRS and the Submillimeter Array (SMA).

The first paper has been accepted for publication, while the second was published on May 13 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters respectively.

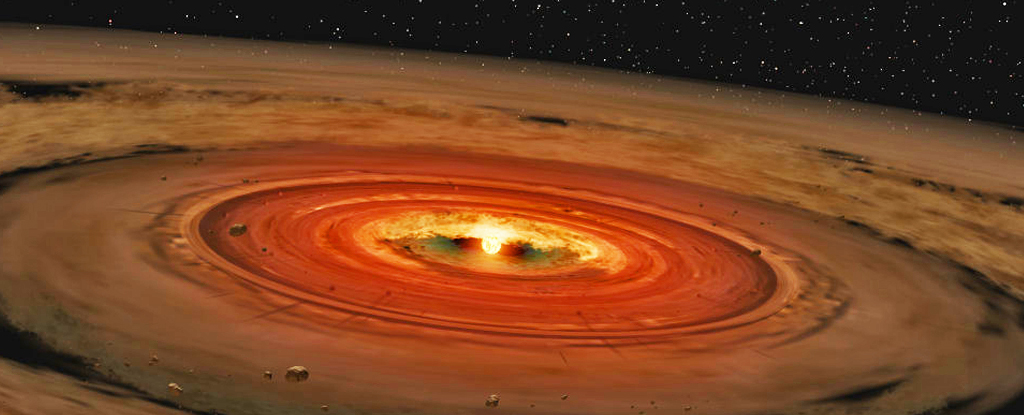

Protoplanetary disks are essentially planetary nurseries made up of gas and dust deposited around newly formed stars. Over time, these disks become rings as material in certain orbits coalesces into protoplanets, where they will eventually become rocky planets, gas giants, and icy bodies.

For astronomers, these disks can be used to constrain the size and mass of young stars as they rotate with a specific signature. Unfortunately, obtaining accurate observations of these disks is sometimes hampered by the way they are oriented relative to Earth.

While some disks appear “face-on” in the sense that they are completely visible to observers from Earth, some planet-forming disks (such as IRAS 23077) are only visible “from the side”, meaning that the disk obscures the light coming from the mother star comes. Nevertheless, the dust and gas signatures of these disks are still bright at millimeter wavelengths – which is what the SMA observes.

When the Pan-STARRS and SWA teams observed IRAS 23077 using the combined power of their observatories, they were quite surprised by what they saw.

Kristina Monsch, an SAO astrophysicist and a postdoctoral researcher at CfA, led the SMA campaign. As she shared their findings in a recent CfA press release:

‘After discovering this possible planet-forming disk from Pan-STARRS data, we were keen to observe it with the SMA, which would help us understand its physical nature. What we found was incredible – evidence that this was the largest planet-forming disk ever discovered. “It is extremely rich in dust and gas, which we know are the building blocks of planets.”

‘The SMA data gives us compelling evidence that this is a disk, and coupled with the estimate of the system’s distance, it orbits a star probably two to four times as massive as our own Sun. Using SMA data, we can also weigh the dust and gas in this planetary nursery, which we have found contains enough material to form many giant planets – and to distances more than 300 times greater than the distance between the Sun and Jupiter!”

After Berghea observed IRAS 23077, he proposed the nickname “Dracula’s Chivito”, an homage to “Gomez’s Hamburger”, another protoplanetary disk visible only from the side.

First, because Berghea grew up in the Transylvania region of Romania, close to where Vlad the Impaler (the inspiration for Bram Stoker’s story) lived, he imagined Dracula.

Growing up in Uruquay, Berghea’s co-author Ana suggested ‘chivito’, a hamburger-like sandwich and the national dish of her ancestral country. Co-author Joshua Bennett Lovell, an SAO astrophysicist and an SMA Fellow at CfA, said:

‘The discovery of a structure as extensive and bright as IRAS 23077 raises a number of important questions. How many of these objects have we missed? Further investigation of IRAS 23077 is needed to investigate the possible pathways for planet formation in these extremely young environments. and how these might compare to exoplanet populations observed around distant stars more massive than our Sun.”

The discovery of this disk also stimulates astronomers to search for similar objects in our Milky Way. These observations could provide valuable information about planetary systems at the earliest stages of their formation, leading to new insights into how the Solar System formed.

The SMA is a series of telescopes in Hawaii that are jointly operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (ASIAA) in Taiwan.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.